By Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera

Perhaps home is not a place but an irrevocable condition.

-James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room.

Twenty-one years ago, I moved from Massachusetts to Spain to become a professional soccer player. I came back nine years later, a Hemingway Scholar. Retracing his steps from Chicago to Montparnasse to Madrid to Calle Obispo in Havana has been the axis of what I teach and write, and an existential foundation to just about everything else. This year my great expectations for a literary summer ended with an e-mail alert that my San Juan-Madrid flight was cancelled.

It wasn’t only a literary trip. Spain is a part of my life: nine years isn’t traveling. Seasons change; so do you. The foreign becomes familiar—it becomes you or you become it, depending on your age.

Once a student asked me if I grew up in Spain. “I first went when I was 21,” I said. “But yes. I grew up there.”

Thinking about those years is like hearing a xylophone: The time I yelled ¡Bona nit! to King Juan Carlos I outside the subway. Talked Hemingway en castellano before a room full of professors. Scored headers in the rain. I even got engaged at the Madrid airport, like some movie script–my wife was about to board a plane to Ecuador while I would catch a bus back to Barcelona. (We both got home about the same time.)

Experiences like that are remarkable in how they don’t retreat from our consciousness. And how they change who you can become.

I want to go back to a Spain I am not sure exists—walk up to the newspaper kiosk where I first heard Catalan and the phonebooth on Avinguda Diagonal where I used to call my wife. Visit the restaurant in Pedralbes where a waiter asked Gabriel García Márquez if he knew how to read (his wife calmed the storm that ensued).

But the canceled trip wasn’t a Homage to Catalonia. In fact, it was about Hemingway in Spain, the Basque Country, and France.

The plan was to trace The Sun Also Rises in reverse: Flight to Madrid. Train to San Sebastián. Train to Pamplona. Bus to Burgete. Car rental to Bayonne. Train via Bordeaux to Paris. Walk from Montparnasse through the Latin Quarter across the river to the Tour Saint Jacques. Though I’ve been to all of them (except Burguete, where Jake Barnes and company fish in the Pyrenees), my return had a pilgrimage feel, like the places themselves retain some genius of what happened to Hemingway there. Some magical residue untouchable on the page.

When I found Ernest Hemingway, my Spain was strange, mysterious, mystical almost—I spoke castellano but knew soccer was the real language of entry. The form of communication that meant more than anything else. I learned new accents and vocabulary, added some of my own terms to the local tongue. I read about Hemingway’s Spain at night, when the streets of L’Hospitalet were dark and quiet. Shadows moved about me on the bedroom wall, muddy cleats sprawled on the floor.

In the end I probably played soccer too long. Fútbol had become my canvas, my coping device, my literature. Those faces in the midfield, petals on a wet back bough.

One afternoon, a teammate, five years my junior, tore his ACL. I saw myself on his crutches and it was enough. That Spain ended when I left the training room that day. Strangely I didn’t miss the game afterwards, and still don’t.

As we assign meaning to experience, culture and identity and travel become intertwined. I remember trips to Puerto Rico when I was a boy, to see my grandparents. Memories from those days in Aguadilla occupy huge blocks of my mind and my consciousness. But I spent much more time elsewhere. “Home” was always Massachusetts. Travel away from the Cape Cod of my youth meant a confrontation with the building blocks of being—language, kinship, community, and those flexible and abstract limits of “we” vis-à-vis “they”.

I don’t think Hemingway’s Michigan, or his Paris or his Spain, were much different in his memory.

The fleetingness of travel allows those paradoxical situations to occur. The apparent stability of “home” offers the calm necessary to reflect on them.

Since 2008, when I left Spain, the place has changed in my mind – so has the language. I speak Spanish every day, more than English, but the accents in Puerto Rico ring other bells, touch other timbres (that’s a translingual joke, in case you’re familiar with Spanglish).

What travel does, if it is any good, is to push people to think about their world, to abandon hardened ideas. To expose fantasies and legends. It is an experience that evokes questions that askew answers and fixed ideas. In that way, travel cures certainty.

Some years ago, Bickford Sylvester called Ernest Hemingway “at bottom a travel writer, performing the traditional novelist’s function of helping us measure ourselves by and against precisely described exotics.”

It is true that wine, sun, and bulls mean something specific to a person from Chicago or Massachusetts or Ecuador—and Hemingway was able to tap into that. But his writing penetrates beyond precise descriptions.

Ernest Hemingway’s prose possesses Spain in ways I feel but cannot put into words.

I want to feel it again, in person not just through literature, and to see Spain through the lens of Puerto Rico—my home since 2009. It will be a Spain without soccer, with a wife and sons, but with the same books.

However, Coronavirus has made this year unique: we must look at literature, Spain, the Latin Quarter, and Hemingway, without moving.

Travel, for all its power, is a tool for writers like Hemingway: death, grief, passion, love, confusion, anguish, normalcy, and language all occur differently in different places. Words are a crucible of that experience. English was a tool of Hemingway’s trade. But so was Spanish, a language he spoke more often than English in Cuba. And so was Spain, so was Paris. So was the space between them, and movement from one to another.

Beside reading his novels, what is the best way to understand Ernest Hemingway? Standing in the bedroom where he was born? Following Jake Barnes’s steps through Madrid? Writing a postcard at Café Iruña in Pamplona? Talking to Cuban fishermen in Cojímar?

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Mutiny on the Bounty was written on Martha’s Vineyard or El otoño del patriarca came into existence in Barcelona, under Franco. Where we are sets terms of what can be written. The implication is that an author’s words never quite match what the reader sees. But we can approximate: once I had been in Cuba and gotten to know Raúl and René Villarreal, breakfasted in Cojímar alongside fishermen in their skiffs, heard the Spanish accents and vernacular of Madrid, Pamplona, Sevilla, and San Francisco de Paula (Hemingway’s Cuban neighborhood) Hemingway’s English began to make more sense to me.

English-centric perspectives and the “American” label misunderstand Hemingway.

Those thoughts are radical—sacrilege, in literary studies—until you’ve had them. Then they’re commonplace.

Upon receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954, Hemingway gave just one interview, in Spanish. And he was drunk. In this vino veritas, he said he was “the first Cuban” to receive the award. Several times, always in Spanish, Hemingway said in public he was a citizen of the island. One time at the airport he kneeled and kissed the Cuban flag. His FBI file describes this as “subversive”.

Guillermo Cabrera Infante called himself the “only English writer working in Spanish” – and Hemingway was a sort of Cuban inverse. He wrote Cuban and American literature, but I am not sure the immense worlds within his English are accessible from only one place, only one perspective, only one language. In order to see, perceive, and interpret the angles of what Hemingway called remate, do we need to experience them for ourselves, building understanding over time? Do we need to see what Hemingway saw, for ourselves?

Isn’t it pretty to think so?

It is true books change meaning depending where we pick them up. And this can be intense. The same words dislodge new timbres, plot directions; the chasms beneath echo explosions that were always there and always sounding. But we couldn’t hear them. Readings like this mirror oneself, or who we are in one place, and while changing the depths of a book can be unsettling, what occurs on the road is fascinating: travel reads you.

After years of traveling in Spain, Hemingway converted to Catholicism in the mid-1920s—he would be obsessed with the Camino de Santiago for the rest of his life. The Cuban-Spanish character in The Old Man and the Sea, named Santiago, moved from the Canary Islands to Cuba at 22 (Hemingway’s age when he left home in 1921). Hemingway donated the Nobel Prize medallion to the pilgrimage shrine of the Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre, in the Cuban city of Santiago.

Hemingway used writing, Catholicism, Spanish, and pilgrimage to navigate mental instability just as Van Gogh had done with color on canvas. But he concealed this in plain sight on the page, through clean language and unadorned writing.

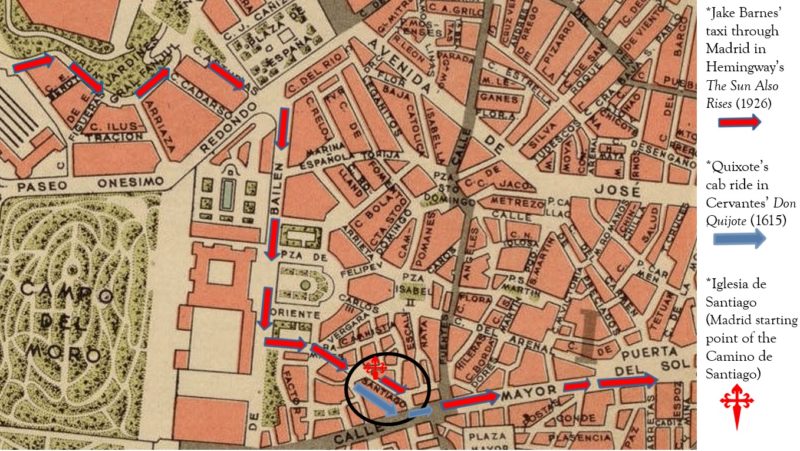

So much happened to Hemingway on an unremarkable streetcorner in Madrid, where he returned over many decades. He knew the literary history of the neighborhood: a scene in Don Quixote and one in The Sun Also Rises involve a taxi ride on the same street, Calle de Santiago. In the shadow of the cathedral that was once a mosque, Jake Barnes and Don Quixote embark on the first steps of the Madrid route of the Camino de Santiago.

Navigating google streetview on the same thoroughfare, holding my son Santiago’s hand steady on this keyboard, it is all on my mind.

***

Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera is a professor of Humanities at the University of Puerto Rico.