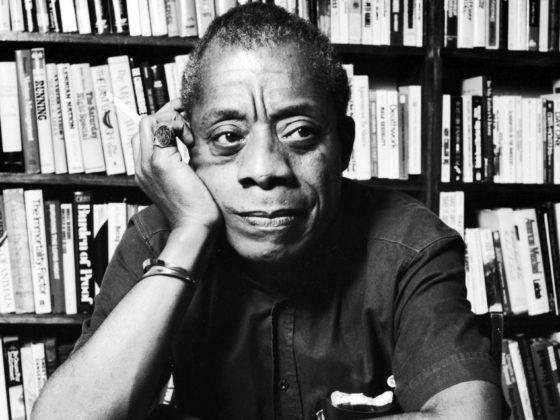

By Angus Cunningham

On a discreet mountain edge overlooking the village of Morgiou, I thought I’d found the perfect spot to bivouac, but things quickly went downhill from there on. It started with the occasional sounds of rummaging in the scrubland above me. This happened each time I was quiet, purposely prolonging movement. When the last remains of daylight vanished, the prospect of what could be lurking out there in the dark, really began to cloud my sanity. What previously was a sublime mountainous view overlooking a tiny French village, began to feel more like a hunting ground, though I was the prey. Finally unable to bear the anticipation any longer, I got up and turned my headlight on. I couldn’t believe what I saw. There were eyes in the bushes, watching me.

Let me stop there for a minute and explain how I got here.

Tired of riding public transport across Western Europe, I wanted to experience the in-betweens of destinations. Throughout most of human history, people have traveled on foot, therefore physically earning the places they ventured to. Nowadays, we take transportation for granted. We close our eyes, listen to music and Voila! We’re in Barcelona. There’s nothing wrong with this. In fact it’s incredibly convenient, but I desired the accomplishment of arriving somewhere on foot.

That’s when I discovered the Massif des Calanques, an emblematic stretch of mountainous coast in Southern France. This wild and rugged landscape extends between France’s second biggest city, Marseille, and the fishing town of Cassis. It’s also the only national park in Europe to be terrestrial, marine and peri-urban at the same time. This Mediterranean wonder, being a haven for those seeking pristine beaches or epic hikes, is one of the most beautiful places in Europe. At the heart of the national park lies monstrous limestone cliffs, scored with deep valleys. These rock-formations were formed millions of years ago, perhaps in the Messinian Salinity Crisis. To experience how humans travelled before the invention of public transport, my plan was to walk from Marseille to Cassis via the Calanques National Park.

Fast forward to the end of June, my Airbnb host, an ex-military veteran, whizzed me down to the start of the trail on his motorcycle, but I was more afraid of his driving than the hike itself. Despite a few errors and miscalculations, the first night went exactly as planned. I reached the port of Callelongue around four o’clock in the afternoon, the place often referred to as “le bout du monde” – the end of the world. Beyond the port marks the entrance of the national park where the wilderness begins, hence the end of the world, or at least of civilization.

Just a mile away to the east, I spent the night on the shore of Calanque de la Mounine, a small enchanting inlet known for its sea urchins, scorpion fish and starfish. This narrow cove is overlooked by an old abandoned semaphore. Listening to the waves rocking back and forth, I noticed an example of the national park’s remarkable biodiversity. This psychedelic yellow-silver ragwort was growing out of the cracks in the rocks. What a strange, yet beautiful plant to sit beside. When darkness fell, the slightest sounds of the wild magnified. The great ocean crawled toward me, wave after wave, but never quite reaching. Tiny little plants shivered in the breeze. The buzzing insects struggled for a bite of fresh blood. My surroundings felt infinite, though I tried to blend in. Eventually, I drifted off to sleep, but was woken a few times by passing helicopters and park guards in speed boats. It’s illegal to wild camp or bivouac in the Calanques, but knowing that most wild camping tends to be illegal nowadays, I justified this knowing I’d leave no trace. Luckily due to the shape of the rocks, the boats couldn’t see me, but the helicopter remained a risk. When their noise faded away, the enchanting stillness of the wild reappeared. I was alone, once again.

My memory of the following day is unforgettable. The trail markings led me along the oceanfront scrubland past the creeks of Marseilleveyre and Queyrons, appearing an awful lot like the Wild West. Then I moved past the winding cliffs of Podestat, L’Escu and Cortiou, which at times beneath the trees, felt like a tropical rainforest. The cool morning air and relatively flat terrain allowed me to cover a great distance swiftly, but approaching Sormiou at midday, the sun grew harsh and uncomfortable and shade was scarce. At one point traversing a steep climb, I could hardly bear the heat’s intensity. Walking in the Massif des Calanques is strongly advised against in the summer months due to the risk of wildfire. Regrettably, it was too late to turn back.

Many miles were trekked before a realization dawned on me. If I continued following the trail, there’d be nowhere else to fill up water and I’d be running on empty. The prospect of this was far too dangerous to attempt, so I detoured towards the small port village of Morgiou, where I hoped to camp nearby and find water before the following morning. The trek was torturously hot and difficult, but with evening just around the corner, the mountains opened up and the village appeared from above. The view was out of this world, but I was too exhausted to fully appreciate it. Feeling sick and defeated, I desired nothing more than the comforts of home. I probably would’ve quit if there was an easy exit, but there wasn’t, so I sucked it up and played tough. Tomorrow, I told myself, I’d make it to Cassis and sleep in a nice, comfortable bed. That thought alone, was the one thing that kept me going.

Mother nature painted the cliffs in a warm, pink glow of wonder. As night fell, the darkness replaced the pink. That’s when I heard the sounds of rummaging in the scrubland above me. Finally mustering the courage to confront the eerie unwelcoming presence, I turned my headlight on. I couldn’t believe what I saw. There were eyes in the bushes, watching me. I packed away my things as quick as I could and ran down the mountain in the dark, slipping once or twice on loose rocks. Though probably just a rabbit or fox, the prospect of being stalked by a wild boar was deeply alarming. These nocturnal hunters are the apex predators of the Massif des Calanques. What a coward, I thought, sneaking through the village in the middle of the night, too naive to endure the harsh realities of the natural world.

On the rocks above the village port, I slept out in the open beneath the stars. It was so quiet out, I heard the cracking open of beer bottles on numerous occasions. Within the shadows, I listened to the villagers chattering inside their homes. These humane sounds were terribly comforting compared to the amplification of wildlife, particularly the beautiful French language. Across the water on the other side of the port, cigarette sparks indicated figures in the dark, but nobody knew I was out there. There was something deeply special about this moment, but I’m still unable to put the feeling into words.

The following morning, fishermen were loading up the boats. For whatever reason, I remembered that near Morgiou was the Cosquer Cave, an underwater cavern with prehistoric rock art engravings. Despite the dread of the night before, it felt amazing to have slept in a place surrounded by so much history. I walked on, keeping that in mind, remembering that soon I’d be back to civilization. Traversing the steep mountains, a wild rabbit sprinted across the trail in the distance, reminding me of something I’d previously read. How eastward from Sugiton, lies the wildest part of the Calanques. The higher I scrambled towards Mont Puget, the highest peak of the mountain range, the fewer hikers I saw. Difficulty increased, beauty intensified, the weight of my bag made all the difference. Here, vegetation was few and far between, but amidst the rocks and granite, wildlife was everywhere.

Deprived of motivation, a chosen song guided me through the struggle. I choose not that of usual stimulation to inspire fearlessness, but a quiet romantic ballad to soothe the heart, a song titled “Take It With Me” by Tom Waits. At the beginning of the song, following a bittersweet piano introduction, Tom sings “The phone’s off the hook, no one knows where we are.” I imagine he’s referring to himself and I as we journey together in spirit, bearing the consequences of this lonely mountain footpath. When I pause for a moment to gaze upon these majestic cliffs and miraculous limestone formations, I pick up a small rock from beneath my feet. Whatever happened from there onward, accompanied by this little fragment of the mountain range, I’ll never forget the wild coast of Marseille.

Angus Cunningham is a traveler based in London. When not on the road, he spends his summers roaming the hills of the South East, and winters photographing London’s back streets, parks and waterways. Wherever he is, be it home or a thousand miles away, he tries to see the world through a traveler’s eyes. For Angus, there’e nothing more thrilling than discovering somewhere new.