By Isabel Cristina Legarda

Savannah is famous for its ghost tours, beautiful mansions, green spaces, and foodie experiences, but I visited as a literary pilgrim. The city did not disappoint. According to NPR, Savannah became a literary tourist destination after John Berendt’s besteller, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil—known to locals as “The Book”—catapulted the city to worldwide fame 30 years ago. But I didn’t go there because of this book. I went there for Conrad Aiken and Flannery O’Connor.

Upon arrival, my husband and I had lunch at the Olde Pink House, rumored to be haunted, as so many places in Savannah are (their ghost allegedly locks women into the downstairs ladies’ room). A delicious lunch of blue crab beignets and salad fortified us for a post-lunch stroll to Oglethorpe Avenue to find Conrad Aiken’s childhood home.

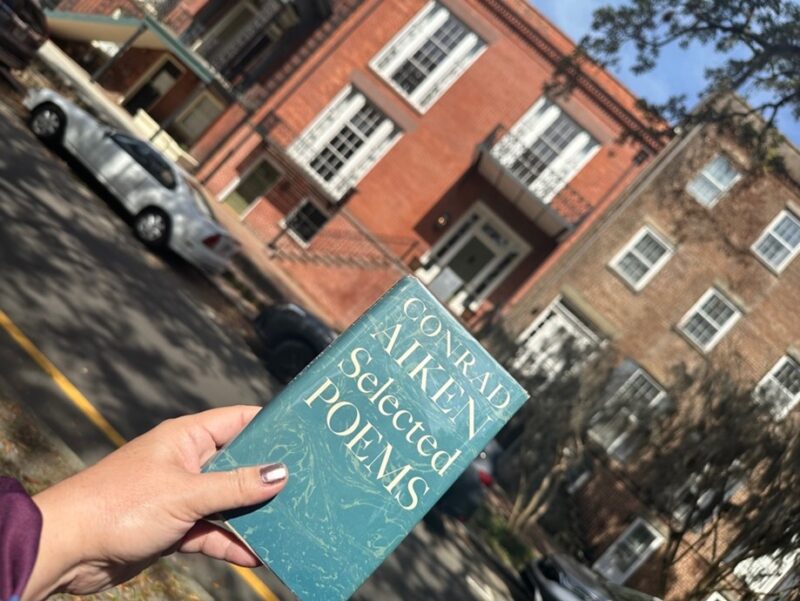

Aiken, who won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award and was poet laureate of the United States from 1950 to 1952, wrote the lines, “Music I heard with you was more than music, / And bread I broke with you was more than bread.” I first learned of these words from Madeleine L’Engle’s book Two-Part Invention, in which she recounts that her husband Hugh Franklin read them aloud before asking, “Madeleine, will you marry me?” L’Engle took the title of another of her books, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, from Aiken’s poem “Morning Song of Senlin.”

Prior to learning about Conrad Aiken through L’Engle, the Aiken that dominated my reading life as a child was Conrad’s daughter Joan Aiken, who wrote the beloved classics The Wolves of Willoughby Chase, Black Hearts in Battersea, and Nightbirds in Nantucket, among others. Aiken suffered unimaginable trauma at the age of eleven when his father, William, a physician, shot Aiken’s mother, Anna, and then himself inside their home at 228 East Oglethorpe Avenue in the early morning hours of February 27, 1901. Aiken heard some of the heated argument that led up to the shooting, heard his father count to three, and heard the two gunshots that took his parents’ lives. He wrote about the incident in Ushant: An Essay, which he described in his preface to Three Novels as a “kind of autobiography, narrated in the third person”: “after the desultory early-morning quarrel, came the half-stifled scream, and the sound of his father’s voice counting three, and the two loud pistol shots and he tiptoed into the dark room, where the two bodies lay motionless, and apart, and, finding them dead, found himself possessed of them forever.”

Different accounts exist about the aftermath. Some say Aiken took his three younger siblings, Kempton, Robert, and Elizabeth, and hid with them among the tombs of Colonial Park Cemetery across the street until dawn. Others say that he immediately went barefoot and in his pajamas to the police barracks a block away to cry for help. In the wake of this tragic murder- suicide, Aiken moved to Massachusetts to live with his great-aunt. Eventually he attended Harvard where, alongside T.S. Eliot, he served as an editor for The Harvard Advocate, the oldest continuously published art and literary magazine in the United States. Later in life he divided his time between Rye, England and Boston, then lived in Brewster on Cape Cod and wintered in Savannah at 230 E. Oglethorpe, the house next door to his childhood home. His childhood house is privately owned and, at the time of this writing, for sale.

Loss became a prominent theme in Aiken’s work. Perhaps the “stone pain in the stony heart” in his lyric “Sea Holly” alludes to a sorrow he carried all his life. His most explicit explorations of childhood trauma can be found in his fiction. Aiken wrote novels and short stories as well as poetry, and he might have been searching for comprehension of, or healing from, his childhood in stories like “Silent Snow, Secret Snow” and “Strange Moonlight.” In “Silent Snow, Secret Snow,” a twelve-year-old boy tries to escape reality by daydreaming about snow, eventually losing his hold on real-world relationships entirely and embracing the interior world he has created for himself, at the expense, perhaps, of his own sanity. The young boy in “Strange Moonlight” learns his friend Caroline has died from scarlet fever, and he wonders, “How was it possible for anyone, whom one actually knew, to die?…The indignity, the horror, of death obsessed him.” He fantasizes one night about having a conversation with Caroline in which he asks her what death is like and if he can come play with her in Bonaventure Cemetery.

To try to help his mood, his parents take him for a picnic on the beach near the black-and-white lighthouse on Tybee Island. When they return home, the moonlight on his house and his body make him feel that “Everything was changed and ghostly,” and removing a shell from his pocket and putting it on his desk, he realizes with new understanding that Caroline is dead.

Conrad Aiken himself is buried in Savannah’s atmospheric Bonaventure Cemetery, in a plot just across from the obelisk in section H, where his parents and third wife, Mary, were also laid to rest. Bonaventure Cemetery—lovely and mildly spooky all at once—is about fifteen minutes by car from downtown Savannah and is worth a visit, with its bluff overlooking the river and avenues lined with live oaks and azalea bushes, which were just starting to bloom in mid- March.

In downtown Savannah, we had our pick of many house museum tours on offer, but I couldn’t pass up the chance to visit Flannery O’Connor’s childhood home. Built in 1856, it sits on the corner of Lafayette Square at 207 East Charlton Street. Our guide at the O’Connor house told us that Lafayette Square had once been quite run-down, with the gorgeously renovated Hamilton-Turner House just across the street—rumored to be the inspiration for Disney’s Haunted Mansion ride—boarded up and, at one point, taken over by a squatter who threw raucous parties. Today the square is one of Savannah’s numerous beautiful green spaces that dot the city every few blocks in all directions, all shaded by majestic, Spanish moss-draped oaks surrounded by other trees such as crepe myrtle and sycamore, flowers, benches for rest and relaxation, fountains in some cases, and interesting monuments.

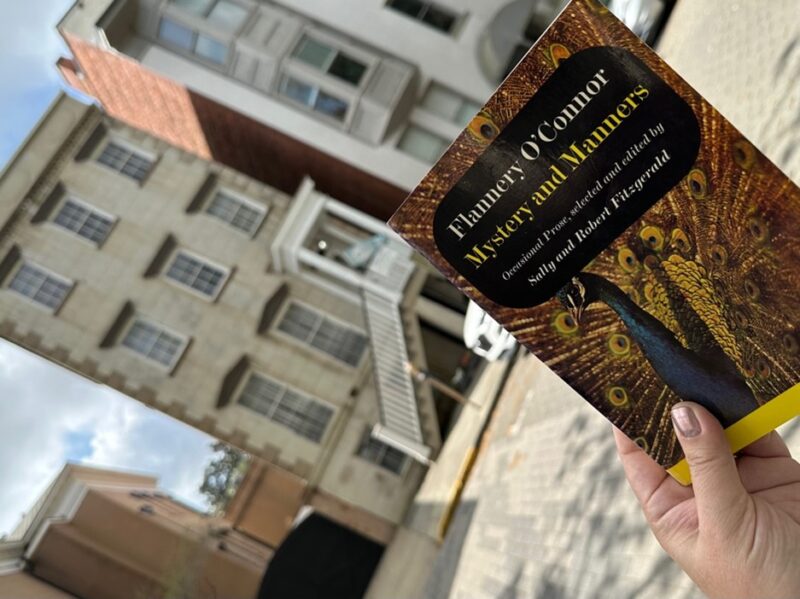

I consider Flannery O’Connor one of my literary mentors. I owe her so much of my intellectual growth as a young person and my development as a writer. She’s less widely read in schools than she used to be, perhaps even less now due to the recent controversy fomented by Paul Elie’s New Yorker article accusing her of racism (despite the dramatically and deeply anti-racist content of her literary output). But at my Catholic high school in the late 1980’s (Connelly School of the Holy Child, Potomac, Maryland), where a progressive and rigorous English department had us reading novels such as Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston as well as classics by Homer, Sophocles, Shakespeare, and Charlotte Brontë, Flannery O’Connor’s short stories were required reading. We read all the greats: “Good Country People,” “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” “Everything that Rises Must Converge,” and my favorite, “Parker’s Back.” I read beyond the syllabus while in high school and fell in love, too, with her nonfiction works, Mystery and Manners and The Habit of Being. It was she who first led me to the insight that good stories come, can only come, from well-developed characters. Our visit was magical for me, in great part because executive director Janie Bragg was such an exceptional tour guide. We learned how as a child O’Connor made outfits for her chickens and wrote criticisms in the books in her library, like “Not a very good book” in her copy of The Fairy Babies by Laura Rountree Smith.

The paint on the walls inside is as close in color to the paint that existed while O’Connor lived in the home, not only because those in charge of the restoration were able to conduct interviews of O’Connor’s contemporaries, but also because for thesis research a student at Savannah College of Art and Design painstakingly analyzed and dated scrapings of all the paint layers. The bathroom at the top of the stairs was O’Connor’s favorite room in the home; she would decorate it and host play dates there. We got to see her original pram; her childhood bedroom and the small, round, wooden table she used; the adjoining main bedroom where her parents had a view of the tall spires of the Cathedral Basilica of Saint John the Baptist; her original crib-playpen, the Kiddie-Koop, in that room; several childhood photographs, her baptismal certificate, a report card, and a wonderful letter in her characteristic spunky voice: “On the two or three occasions Brother Kirk and I were left alone together,” she wrote, “our attempts to produce a conversation were like the efforts of two migits [sic] to cut down a redwood tree—furious but ineffectual.”

It’s the power of her voice, in her letters and essays as well in her fiction, that keeps me

coming back to Flannery O’Connor again and again. Her creative writing can be hard, even off-putting at first, but it is profound. I’ve told students in the past, “You might find youself asking in your mind, while you’re reading, ‘Why on earth am I reading this?’ then come away with so much that will haunt you and make you think.” She spoke and wrote about writing, prayed about it, and approached the work with tremendous discipline and tenacity, writing in the Southern Grotesque genre when most readers, including those closest to her, connected more easily with works like Gone with the Wind. She wrote with unflinching ethical focus, informed by her Catholic faith, intent on exploring questions of evil and grace in a world often violently resistant to holiness or even its own humanity. When I think of her writing my favorite story “Parker’s Back” while suffering with lupus in the hospital during the last few weeks before her death, determined to finish, I am filled with awe and gratitude—and a little embarrassment at all the times I’ve ever complained about how hard it is to keep writing.

Flannery O’Connor died of complications of lupus at the age of thirty-nine in Milledgeville, Georgia on August 3, 1964. Because I feel connected to her as a person as well as a writer, I look at her life and am left, like the child in Conrad Aiken’s story, with the incomprehensibility expressed in the question, “How is it possible for anyone whom one actually knows to die?” A person’s voice, especially, makes her present to us; she is still here, still with us—we can hear her, feel her. Flannery O’Connor haunts Savannah, wonderfully, and will continue to haunt the world, not as a lost wraith floating through the graveyards and Spanish moss, but as a living voice inhabiting her stories. “A story,” she wrote in Mystery and Manners, “is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the story to say what the meaning is.” I keep her words close and write on.

Isabel Cristina Legarda born in the Philippines and spent her early childhood there before moving to the U.S. She is currently a practicing physician in Boston. Her work has appeared in the New York Quarterly, Cleaver, HerStry and others. Her poetry chapbook Beyond the Galleons was published in 2024 by Yellow Arrow Publishing. www.ilegarda.com Instagram: @poetintheOR.