by Audrey Herrin

The feeling started to come over me after that second iced coffee. That, and being thoroughly charmed by Lewis, my Tinder date who I had only met once before. We were sitting cross-legged in the park with our takeaway coffees and books in our laps, listening to music on his speaker. From the beginning, it was easy to be comfortable with Lewis, as if we were old friends.

“It’s such a shame that I’m driving back to San Francisco this afternoon,” he said. “I wish we could see each other more.”

“Ugh, I’m so jealous,” I groaned, “I’ve always wanted to go to San Francisco.”

It was true. Since I first read On the Road by Jack Kerouac in high school, my dreams were haunted by the mystical city at the end of the continent. The home of the Beat generation. Even as I outgrew my idolization of the Beats, On the Road was still one of my favorite books of all time.

By this point, at age twenty, I found the flawed legacy of the Beats difficult to ignore. Especially as a woman. On the Road is no longer a radical text in our time. It is an individualistic, masculine fantasy (something the US doesn’t need any more of right now). A work of art tainted by misogyny, narcissism, and outdated ideas around race. Yet, like many others, I couldn’t help re-reading On the Road again and again. There is something about it that continues to inspire readers with a lust for new experiences. It’s impossible to escape the energy it ignites in you.

The name of the city felt enticing on my tongue. The many-syllabled, Spanish name butchered into a new, fabled meaning by the American-English accent, San Francisco, San Francisco…

“I have some weed in my car,” he said, “I was planning to camp out at Crater Lake tonight, smoke, and listen to a Spotify recording of Jack Kerouac reading some of his poetry.”

The feeling that came over me crystallized. The feeling was the urge to throw my life into the hands of fate.

“Wanna come with me?” He asked.

He was joking.

“Yes,” I said.

I wasn’t.

I stuffed some things into a bag and called my parents with a fabricated story. Less than an hour later, I was in his car. A yellow Mustang, packed with all his belongings from his summer spent in Seattle for an internship.

“Are you sure about this?” He asked, “we barely know each other. You can change your mind.”

“I’m sure.”

We merged onto the freeway, and soon we were hurtling away from Seattle into the pink summer haze.

When Kerouac wrote On the Road, he attached several sheets of paper into one continuous roll and stuffed that into his typewriter so he didn’t have to pause in his writing. He wrote in spontaneous bursts of inspiration, without regard for traditional plot and structure, and wrote and wrote, following the current of his thoughts.

He traveled the same way. No itinerary, no plane tickets, no packing list, barely enough money in his pocket to get by. He just followed the impulses that sent him across the country and figured it out as he went.

Now, I was doing the same.

In this modern world, it is easy to avoid spontaneity, but there I was. No plan, no return flight, no place to sleep at night, at the mercy of a man I barely knew. It was liberating to surrender to the flow. To decide that one way or another, everything was going to work out.

We weren’t chasing any kind of deadline, and stopped whenever something caught our interest on the side of the road. Portland was our first stop, where we had dinner and explored the gargantuan Powell’s Bookstore. Then somewhere in the middle-of-nowhere Oregon as the sun began to set, we parked by some train tracks and balanced on the rails under the tangerine-stained sky.

Kerouac used to work as a brakeman on the railroad in San Francisco, where these same tracks concluded their journey. I thought of his poem “October in the Railroad Earth,” as we climbed parked train cars and ran across their roofs, jumping from car to car.

The ecstatic liberation that Kerouac conveys in his scantily-punctuated, breathless style would have fittingly described my experience in that moment.

For two days we were engaged completely in the scenery around us, following power lines in their perpetual wave pattern along the interstate. We listened to music and talked – learning about each other. When you’re stuck in a car with someone, hurtling across the country together, the only thing to do is to forget all social pretenses and delve deep into the roots of each others’ being.

Another thing I learned from On the Road is to be receptive to the present moment. Once you let go of superficial distractions and open up, you start to notice things more. Like Kerouac, who was known as a great observer.

Power lines, roads, fields, train tracks, they stretch on and on into the horizon in this great flat landscape. These images are recurring motifs in On the Road.

“What do these motifs represent?” Lewis asked.

I couldn’t think of an answer – other than this sensation of weightless stomach swooping that I kept getting.

Then he had to stop talking because a good song came on the radio, and he tapped his fingers on the steering wheel to the beat. He didn’t like to talk while listening to a good song. He gave things the full intensity of his attention, each in their turn.

In the evening, we passed Oakland and flew into the Bay area under a purple sunset. The bay was a sparkling crescent of city lights, and the ocean sprawled out in front of us. It was just like the moment in On the Road when Dean, Sal and Marylou arrive after their long journey across the country and Sal wonders what kind of revelations await them in San Francisco.

Lewis’s family had a nice house in the hills of San Carlos. His family welcomed us with dinner and sparkling wine, and didn’t ask questions.

The morning brought us across the foggy Golden Gate Bridge to an art gallery in Sauselito. The floor-to-ceiling window was filled with the ocean. The paintings were surreal, reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch.

They engulfed Lewis’s attention. His energy was infectious, and he struck up conversation with the gray-haired gallery owner. She was an old woman who told us about her youth spent living ‘la vie boheme’ in Paris.

I never would have spoken to her if Lewis hadn’t been there. He was always interested in the lives of strangers, and knew how to ask the right questions to entice the best stories from them.

This is why I admired him. For the same reason Sal admires Dean in On the Road. Dean is fascinated by the people they encounter on their travels, enjoys getting to know them, ‘digging’ them, and learning from them.

In the DeYoung museum, we encountered a man dressed as an ancient Egyptian pharaoh. There was a King Ramses exhibit on, and we asked if he was a part of the display.

“No,” he said with a grin, “I’m just a big fan.”

Lewis got a kick out of this man’s passion for ancient Egyptian history and was overjoyed to listen to him ramble on about it. When the pharaoh man was gone, he turned to me.

“Oh what a sweetheart,” he said.

He had this way of looking at everyone like he loved them.

It was my third and final day in San Francisco, having booked a return flight for that afternoon. He brought me to his favorite viewpoint overlooking the city.

We spread a blanket on the dirt and gazed down at the city for almost two hours, measured by the distant chiming of church bells. A breeze blew intermittent scatterings of rain from misty clouds. In the distance, the fog crept across the bay. We were alone, except for a red-tailed hawk circling above us, flashing the underside of its wings. Except for a gopher that popped its head from a hole in the dirt nearby. We sat statue-still, shoulder to shoulder like a couple of foxes, so we wouldn’t scare the animals away.

“You know,” Lewis said suddenly, “The freckles on your cheek make a shape like a constellation.”

He brushed his finger across my cheek, tracing lines between them.

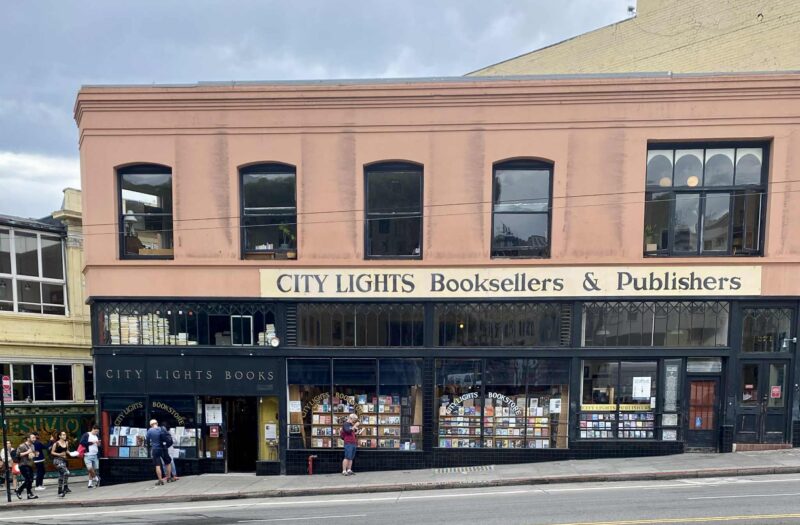

The afternoon found us in Chinatown. The oldest part of the city, and one of the neighborhoods most frequented by Kerouac. With its streets illuminated by lanterns and glowing Chinese characters, it’s like stepping into a different country. Nearby, is Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookshop. The home base for the Beat poets, the little press which published their controversial poetry including Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl.”

I bought a poetry collection by Ferlinghetti. There was a silly poem in it titled “The Love Nut”, which was my favorite. It reminded me of Lewis.

We wandered the piers together, killing time until my flight. Then he was hugging me goodbye in the BART station and I was hurtling underground, away from the city towards the airport, smiling as I recalled how Lewis always holds his breath in tunnels.

At the airport gate, I flipped through the poetry book and looked around to see if there was anyone who would talk to me. I wanted to engage with the world, but no one would look up from their phones and laptops, so the ordinariness of existence continued and no one spoke to me.

Kerouac would have kept going. He would’ve ventured further South into unknown lands to meet new people and learn all about them and fall in love with them too. But there was work on Monday, and obligations to fulfill, and parents who would worry.

As the plane took off, I began scribbling notes in my journal. San Francisco shrank beneath me and disappeared under the clouds. Goodbye San Francisco, I wrote. Goodbye to the frosted wedding cake houses, the buoy-sprinkled bay, the ghosts of Beat poets on street corners, the mist clinging to the air, and the tram tracks gleaming on the hills – goodbye Lewis of San Francisco.

“Once again I wanted to get to San Francisco, everybody wants to get to San Francisco and what for? In God’s name and under the stars what for? For joy, for kicks, for something burning in the night.”

– Jack Kerouac

Audrey Herrin is an aspiring journalist from Seattle, Washington, with a degree in English Literature from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. Her work has previously been published in Intrepid Times magazine, among others. She is an avid reader, writer, and traveler; and she writes about her adventures and miscellaneous musings on Substack: @Bookish Backpacker.