By Jessica Monk

“There is no paying life in advance for what it must do to you. It asks of one’s unarmored heart, and one must give in. There is no other way. When you find happiness, take it. Don’t question too much.” – Millicent Rogers

She was a child of the Jazz Age who lived fast and died young, but unlike F. Scott Fitzgerald’s hedonistic characters, her legacy was not the destruction, but the conservation of beauty. She left behind lovingly curated collections of European and Southwestern Native American art, and she was quietly creative, but reporters supplied us with little record of the origins of her inspiration. The press was more interested in her penniless aristocratic foreign husbands and her vast fortune.

Welcome to the life of Millicent Rogers — a beautiful, blonde, fabulously wealthy socialite, but also a stringent aesthete who fought disability with creativity and battled heartbreak with a pioneering spirit. Her friend, the milliner Elsa Schiaparelli, said of one of the twentieth century’s most revered fashionistas: “Had she not have been so terribly rich, she might with her vast talent and unlimited generosity have become a great artist.” But if being unimaginably wealthy gives a person too many choices, it also permits an equally wide range of self-expression. Houses, husbands, pets, dresses, art, influential friends — these are all the superficial building blocks of Millicent Rogers’ biography. But her life was not defined or cut short by excess. It was the opposite. As a child, she was told she would not live past the age of ten, and she made it to 50 years old, before the complications of her childhood rheumatic fever claimed her. Coasting on her vast fortune was not for Rogers; possession became a form of epicurean self-expression. Each object and moment had to matter. When her favorite designer, Charles James, expressed exasperation after she ordered bales of his shirts, her maid corrected him. “Not a hoarder,” she defended her employer, “a collector.”

The title of Cherie Burns’ recent biography, Searching for Beauty, reflects this restless search for perfection in her personal style and in her own creations. She participated in the design of her clothes and even her cars; on a Delage D8-120 Aerosport she sketched out her precise specifications for its redesign with lipstick. And when she chose a place where she would like to be buried – head facing a mountain, wrapped in a ceremonial chief’s blanket — it was a hallowed place.

Taos, New Mexico was a favorite retreat for disenchanted, intellectually hungry artists and writers when Millicent was invited by Mabel Dodge Luhan in the 1940s. Her friend-to-be, the painter Dorothy Brett, or “Brett” as she was known in the Bloomsbury group, was a long-time resident and had come there on the invitation of D.H. Lawrence, fleeing the messy outcome of an affair with Katherine Mansfield’s husband. The two women had a lot in common: both were wealthy, and Rogers, an elegant serial divorcee, was in her own way weary of trotting at the world’s pace. Branded public property as the “Standard Oil heiress” by the media since her debut at the Ritz Manhattan in 1919 (1300 people attended), she was accustomed to handling the press as if it were an excitable toy dog straining at the leash. She was daring and had as much dash as the gentlemen she pursued; she deliberately attracted the attention of Clark Gable by turning up to a party with a pet monkey on her shoulder. And she was witty and cultured, with several languages under her belt.

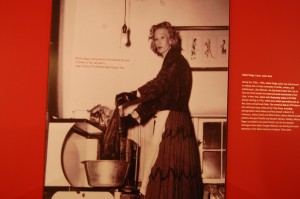

During her frequent bouts of ill-health she learned languages and translated Rilke for fun. A friend was once reported to have asked her: “I’m sorry, Millicent, are we boring you?” “Not yet,” she replied. Rogers often turns up on lists of best-dressed American women – she had a moment at Diana Vreeland’s 1975 exhibition of American Women of Style and again at the Met’s recent American Women exhibition – but in the well-known photographs of her she is almost always an older woman. Her flapper image in the 1920s didn’t catch fire like Zelda’s did; it was when she had mastered the raised eyebrow, established collaborations with designers like Schiaparelli and Charles James, and defined her own style: statuesque, coiffed blonde with a dramatic, cinched silhouette and pounds of striking jewelry, that the most memorable images of her were captured.

She was not a late bloomer though, more a seasoned survivor. She brought the rich fluorescence of her personal experience to Taos after a life of headlong excitement. On the verge of her escape to Taos, after finding Clark Gable in the arms of another woman, she wrote: “There is no paying life in advance for what it must do to you. It asks of one’s unarmored heart, and one must give in.” And then she mailed two copies of the letter: one to Gable himself, and one to the LA Times.

It was a poised exit, and in Taos, she began to devote her money and influence to new causes (she had been offered a Legion of Honor by the French government for her relief work in WWII): the civil rights of the Native Indians of Taos Pueblos and a bid to get Native American Art recognized as “historic,” so it would be protected. She worked with writers Oliver LaFarge, Lucius Beebe, and Frank Waters to hire lawyers to go to Washington and lobby on the behalf of Taos Pueblos.

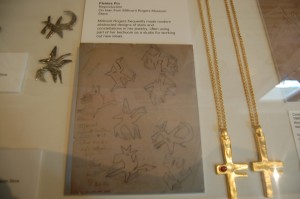

“She knew how to manipulate the press, and in some ways she both loved it and hated it,” says Gwendolyn Smith, curator of the recent exhibition, “Millicent Rogers: Heiress, Fashion Icon & Her World.” The exhibit at Long Island’s Planting Fields Arboretum attempts to piece together the personality of Rogers, the Chairman of the Planting Fields Foundation’s fondly remembered cousin, through newspaper clippings and artifacts from her life. Yet this keyhole vision into her soul – through the glass cases containing her handmade silver jewelry, her hand-dyed velvet– still feels chilly with the draught of unsolved mysteries. “She knew all the right people, everyone knew her, and yet there was this feeling that she was flitting between things” says Smith. Even her biographers struggle to pinpoint exactly what motivated her creativity. Rogers’ chosen art was silver and gold-working, a therapeutic as well as creative hobby that she practiced to keep her arthritic fingers nimble. She had a contract with Verdura, and she even brought her metal-working tools with her when she traveled. Her striking silver Pleiades and Regulus pins are on display at Planting Fields with the sketches for their designs.

It wasn’t Taos though, or her association with artists and writers, that made Millicent Rogers an artist. Her mother had always encouraged a creative streak in her. She had literary boyfriends – Roald Dahl and Ian Fleming – but apart from her leggy Bond girl looks and her wealth and glamour there is no evidence that she inspired literary characters. She was neither a passive muse nor a full-time artist – she was something impressive and hard to define, a woman with the financial and aesthetic means to express herself in protean ways through the things and people she chose to surround herself with. Her art collection was so impressive that Dahl wrote home to his mother about it; “You could almost hear the gasps throughout the letter,” adds Smith. Throughout her life Rogers casually acquired Monets, Cézannes, and Toulouse-Lautrecs. And although the European art has been dispersed, the museum at Taos remains a monument to her taste and curiosity. The collection of Native American and Hispanic jewelry, exquisite contemporary pottery, Hispanic Art and Textiles doesn’t patronize the culture as one of antiquity. It includes the work of contemporary Indian and Hispanic artists. The founding legend of the museum is the story of when Millicent Rogers – who loved heavy, dramatic jewelry – lifted a many stranded necklace of turquoise from a stall and became hooked on the beauty of native Southwestern art.

We will never know why she chose the theme of constellations for some of her most striking silver jewelry designs, but the radical designs, which simplified constellations into silver rivulets geometrically branching from the co-ordinates of stars were thought of long before she moved to Taos. “There was something cooking inside of her,” observes Smith. It was just coincidence that Millicent was to move to a region of the world where silver-working (introduced by the Spanish) was a big part of the native craft tradition. In 1948, when she was living in a raw adobe house in Taos, Harpers’ noted something “archaic” in her jewelry that might have been attributed to Taos’ ancient culture. But it seemed that her inspiration had found itself there rather than the other way round.

In a similar way, Smith had no idea she would work on exhibitions about Georgia O’Keefe, Ansel Adams, and Millicent Rogers when she visited Taos in 2005. But like many others, she fell in love with the “wide open, very bright blue cobalt skies, and architecture” of the place. Taos still draws artists to live and work there and tourists to the ski-slopes in wintertime. D.H. Lawrence happily worked on novels there during the 20s. Georgia O’ Keefe painted the swelling simplicity of the beautiful Ranchos de Taos church, and her later work became almost synonymous with New Mexico. And the lineage of extraordinary people pitching up in Taos is celebrated in a 2012 book about the women who made their mark in Taos.

There are times when ordinary statements make you stop and think. What does it mean when someone finds what they are looking for; when it takes an undiscovered landscape to fulfill the intangible inspiration in a mind’s eye? Artists who went to Taos found an ideal space to work, as if they had carved it out beforehand in an interior vision. And yet they altered the place with the experiences they brought. Millicent Rogers had more physical baggage, packed in stylish designer cases, than most. But in Taos, a place far away from the values enforced by her upbringing, her approach of conservation and craftsmanship could be recognized as a form of creative expression honoring the variety of life, not just the whims of a wealthy, beautiful woman.

Overshadowed with the threat of untimely death, she packed in as many clothes, homes, lovers, and as much beauty as life could offer. At 50 years’ old she was buried in traditional Native American gear, with her head facing Taos Mountain. The last act played out, there were no more objects of beauty to discover. There was only her life. But if her life was the creation of this passionate, deliberate woman, you get the feeling that she found what she was looking for in her last years in the shadow of Taos Mountain.

Taos and Millicent Rogers: Required Reading:

Searching for Beauty: The Life of Millicent Rogers, Cherie Burns, St. Martin’s Press Buy it on Amazon.

Remarkable Women of Taos, Nighthawk Press Buy it on Amazon.

Georgia O’ Keeffe: A Life, Roxana Robinson, UPNE, 1999 Buy it on Amazon.

Mornings in Mexico, by D.H. Lawrence, Fredonia Buy it on Amazon.

For more on Long Island, check out LongIsland.com

3 comments

Thank you for a lovely article. Millicent Rogers was my grandmother. It was not only a joy to read but very insightful. My two boys have only heard stories about her and this article brought her to life.

I’m really glad you enjoyed the article Lorian. And I am so pleased that I was able to bring her to life for someone who really knew her. I got a sense that she was a very strong, generous personality who lived her life with great enthusiasm. I also really wanted to pinpoint the creative side of her. It seemed that her style, her jewellery and her collections were all crafted with great purpose that makes her still very influential.