By Piia Mustamäki

“You are alone?” The young woman’s raised left eyebrow gave away her surprise. It was Christmas Day during a pandemic and I had just driven 10 miles on a gravel road. The other woman behind the Hobatere Lodge reception didn’t bother hiding her alarm. Both eyebrows raised, she chimed in, “You don’t have children?” “No I don’t,” I answered, flashing a smile I had gotten used to doing and quickly changed the topic to the five elephants splashing at the water hole in front of the lodge.

The check-in continued as usual except that the woman worried about my childlessness kept giving me the side-eye. It was only later I realized she must have thought I was some sort of a witch. During my two-night stay at the lodge, whenever I talked with the other guests or personnel, she would make sure to walk by and whisper a warning over their shoulders: “She’s alone!”

The previous night I had Christmas Eve dinner in a scenic spot overlooking a valley and an arid plateau. I dined with Daniel, a Swiss man who lived in Namibia, and Albert, a Namibian from close to the Angolan border. Itching with curiosity and glancing at each other, they asked, “Aren’t you afraid of driving alone in Africa?” I answered that I wasn’t afraid because I had traveled quite a bit in Africa, though never before driving myself. But the questions continued: “Have there been any problems taking buses in Africa?” “You were not afraid of going to Mozambique by yourself?” Albert, a tall but gentle man, confessed that he would be terrified traveling anywhere alone.

I explained that I had been traveling solo since I was nineteen and that for some reason fear was never the most prominent feeling accompanying me. “It also seems I have good travel karma. At least an Indian guru once told me so.” Albert nodded and said, “Yes, I can see that in your face.”

I didn’t tell Daniel and Albert that I didn’t quite feel like I was traveling alone because I had Martha Gellhorn keep me company. She was a restless wanderer who lived throughout most of the 20th century, working as a journalist and a war correspondent. I knew that the audio version of her only travel book was going to be the perfect companion for my solitary drives in the Namibian outback.

Gellhorn was seventy when she wrote Travels with Myself and Another. In the preface she announces that the book is about “horror journeys” because nobody is interested in trips that went well. One such journey of hers is to Africa. In the early 60s, she comes to some money after selling a short story to TV and decides to travel just for fun. “Travel for pleasure, the most daring idea yet,” she writes with her typical sarcasm. She doesn’t mention that she was fifty something at that time and that she left her adopted son behind.

Her African horror stories are mostly from West Africa: she starts in Cameroon and Chad, which disappoint her. Once she gets to Nairobi, Kenya, she refuses to join an organized safari and insists on renting a Land Rover and exploring on her own. This is in 1962. The British safari guide would only rent her a car on the condition that Martha has company: he picks a young man called Joshua to help with the driving and to protect her.

After driving for ten days, I returned the car and settled in a historic Airbnb apartment in Swakopmund. The Atlantic Coast settlement is quaint but has a racial structure still in place: tourists and descendants of the German settlers live in the center while most blacks in what used to be the townships. The green Neo-Baroque house I stayed at was built in the early 1900s and had at one time served as a brothel for the Germans. A nearby beer garden had a replica of Reiterdenkmal, a statue of a German soldier on a horse, which was toppled in the capital about ten years prior. It commemorates the squashing of the Harare and Nama people’s uprising, which ended in their massacre.

Already uneasy due to Swakopmund’s racial attitudes, I decided it was time to call my mother. I had decided not to feel guilty about spending the holidays traveling. “Didn’t they hesitate to rent a big car like that to a young woman traveling alone?” I chuckled at “young”; I’m in my late forties. On another call, my sister told me about their Christmas Eve dinner in Turku, our hometown in Finland. My big brother had said that he would be too scared to ever drive in Africa.

I had read that Namibia is the second least densely populated country in the world after Mongolia. It has reasonably good roads and is so organized it is often called “Africa for beginners.” This convinced me I could rent a car while I’d never do it in Ghana or Uganda. Yet I was scared but not about Africa: it was handling the car and driving on the left side that made me nervous.

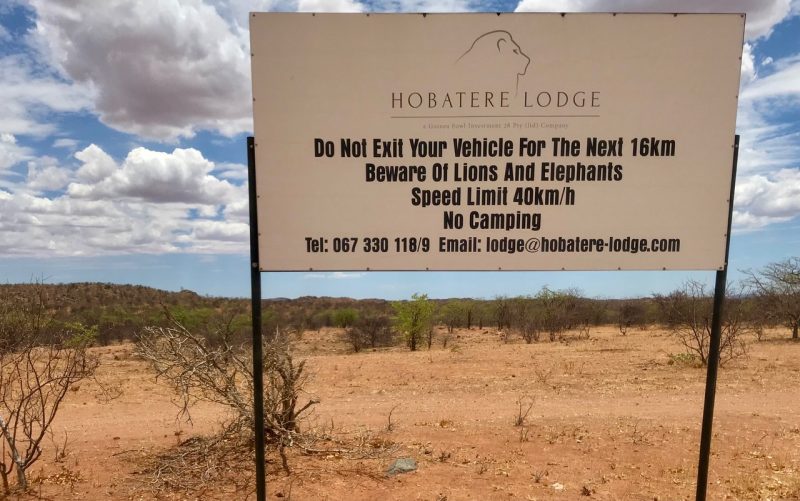

I didn’t tell my mother that Claire, the stocky white Namibian woman running the Windhoek car rental place, had looked hesitant. I felt a little shaky that morning, perhaps still from the flight and dehydration or the lingering cold I brought along from home in Abu Dhabi. David, who had picked me up at the airport, showed me the massive off-road car’s features. I listened about the spare tire trying to hide how insecure I felt: I had no idea how to change one. As I left, David waved and said “take a lot of pictures and remember to drive on the left.” As I drove away from Windhoek in the barren landscape dotted with hills, I slowly got used to the 4X4 diesel monster. Occasional signs reminded me to be aware of elephants and wild boars. The rest stops, marked with acacia tree signs, promised shade from the harsh sun. The further up north I drove the less tarmac and traffic there was and the more I appreciated the sturdy car; it helped me through gravel and dried river beds.

Several times the anti-poaching police stopped me and asked me to open the trunk. The pair of police officers would patiently wait as I struggled with the two manually operated locks each with its own key, which refused to open once filled with dust. Each time the scene was the same: I finally got the trunk open and the three of us stared at my dust covered suitcase and laptop bag lost in the huge and otherwise empty trunk.

I’m not sure why the police just stared in silence. Because they were expecting to find a dead zebra? Or because the desolate view confirmed that I really was traveling alone? “All that work opening the trunk and nothing,” one middle-aged officer said in a lovely, distinctly African accent. “Thank you for doing the work,” I replied, flashing that smile again and climbing back into the big car. I couldn’t wait to put on my headphones to continue with Martha.

Gellhorn is at her funniest as she slowly unravels how Joshua, her so-called protector, is not much help at all. He takes no initiative. He is terrified of the animals she craves to encounter. He is worried about soiling his pointy black shoes and imitation Italian silk trousers. It’s Martha who ends up getting knee-deep in rivers to check whether they’re safe to drive through. It’s Martha who removes trunks from the road with lions and rhinos in close proximity. Little by little she also realizes that Joseph doesn’t know how to drive: he had lied to get the job.

In the end, Joseph helps Martha only by lifting her suitcase in and out of the car and occasionally translating a few words of Swahili. But in appearance he is the one looking after her. Listening to the story, it occurred to me that Joseph is an equivalent of a beard for a gay man: a ruse to ensure the world that both are properly fulfilling their culturally-constructed gender roles; That a fearless middle-aged woman traveling alone isn’t capable of doing it all, that she is in fact as helpless and in need of a man’s protection as the world perceives her. I kept thinking that If I had such a beard with me, perhaps nobody would have stared at my empty trunk or asked me whether I was afraid. Or thought I was a witch.

But I’m not as capable as Martha. I left out the small detail that I damaged the car about ten minutes after renting it. Waving at David, I kept repeating to myself “you’ve got this, you’ve got this”. Somehow I made it to my hotel. But as if in a self-fulfilling prophecy, I lost control of the car entering the cramped uphill lot and hit a metal pole causing a deep dent and scratches on the left bumper. In deep shame, I decided to tell nobody and to deal with it only when I returned the car.

Martha too kept secrets when she felt embarrassed. In Surinam, reporting on the wartime efforts, she realizes there is an un-mapped part up a river. She makes arrangements to go explore it — “how could I not?”– by hiring an unlikable local man, whom she calls “Slicker.” He warns her of the jungle mosquitoes but she doesn’t listen, having already survived the insects in the capital. But she falls very ill and has to rely on Slicker to carry her back. It turns out she caught dengue fever. She tells no one about her thwarted expedition until writing the book decades later.

A few days after I had decided to keep a secret, listening to Martha’s story made me feel better. I felt seen by someone from the previous century. I admired her matter of fact tone and self-deprecating humor. And I flattered myself by finding many similarities between us: a chosen — no: compulsory — nomad existence, an innate curiosity, love for swimming naked and experiencing intense moments of joy while traveling. Martha describes such an occurrence as a “state of grace which can rightly be called happiness, when body and mind rejoice totally together.”

I had hoped to join a group game drive when I finally reached the famous Etosha National Park in Northern Namibia. But it was impossible due to the low number of pandemic time visitors. “Ma’am, you can take your car,” the cheerful receptionist at my lodging pointed out. Etosha is one of few African national parks where you can drive yourself. I imagined the car breaking down in a remote part of the park with no way to ask for help. As if to enable my horror scenario, when I set out at dawn the next morning I forgot my phone in my bush cabin.

I gassed up and bought a map at the little service village close to the park’s southwest entrance and proceeded to drive along remote roads. The flat landscape appeared in soft hues of beige, cream and off-white with some green bushes here and there. Stopping at a water hole, I turned off the engine, opened the windows and listened to the deafening silence. The zebras were quiet and so were the giraffes. Even the birds had decided not to make noise that day.

Further along one of the roads, I stopped to observe baby ostriches. A snake crawled across. A nearby mongoose stood up on its back legs and looked at me curiously. Suddenly a herd of springboks surrounded my car. The delicate tiny antelopes stared at me in the eye, making no sound as they munched on leaves. It seemed as if I had been engulfed in a pastoral scene, allowed to be a part of it. With body and mind in sync, it felt as if Martha had been guiding me here the whole time.

Piia Mustamäki is a Finn, a New Yorker and an academic wanderluster, currently located in Abu Dhabi, where she teaches at NYU’s Writing Program. Her writing has been published in Meridian: The APWT Drunken Boat Anthology of New Writing, Punctuate, The Culture-ist and Matador Network. Her essay “High in Harar” received an honorable mention at the 14th Annual Solas Awards for Travel Writing.