By Katie Steinharter

They say that at the end of the day, we’re all not that different. I disagree. Life deals us all a different deck, and this changes how we respond. It’s not at the end of the day that we’re all similar—it’s at the beginning.

They say that at the end of the day, we’re all not that different. I disagree. Life deals us all a different deck, and this changes how we respond. It’s not at the end of the day that we’re all similar—it’s at the beginning.

At the beginning of First They Killed My Father, young Loung Ung sits at lunch with her parents and says, “I’d much rather be playing hopscotch with my friends.” Wouldn’t we all at five years old? Whether in Cambodia or the USA, hopscotch is a lot more fun than “adult time.” When I was a child I used to dread going to our neighbors’ house because I knew my parents always wanted me on my best behavior despite that I’d rather be out playing in the street with my friends. But young Loung soon had to face a lot worse than just an uncomfortable lunch with the grown-ups.

Ung writes her memoir in the voice of her childhood self. At just five, she learns firsthand about civil war. Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge wanted to eliminate anybody who could be seen as a threat to their reign, thus sending families like the Ungs into hiding because they had connections to the prior government.

Unfortunately, even after fleeing the city to live with virtually nothing, the Ung family learns that only “true” peasants were considered safe. Ung explains, “peasants who have lived in the countryside since before the revolution are rewarded by being allowed to stay in their villages. All others are forced to pick up and move when the soldiers say so.” Despite originally coming from a middle-class city life, families like the Ungs were also told to eliminate electronics from their life—“imports are defined as evil because they allowed foreign countries a way to invade Cambodia, not just physically but also culturally”—and burn any brightly colored clothing—“No! Not my dress!” she cried to the soldiers.

While I was working for an agricultural non-profit organization in Cambodia, I spent a lot of time in rural villages. I interviewed locals to learn how modern technology has juxtaposed with traditional farming methods to increase their crops. I was told stories that were both difficult and challenging, as well as beautiful and enchanting. Eating under the raised thatch home of a rice farmer in the middle of his vibrant green rice fields, I could also picture the Ung family hiding quietly above me for fear that Khmer Rouge soldiers were standing below listening for “traitors.”

The word for green in Khmer is also the word for blue, and if you walk through a big rice field you can understand why. The rice straws grow so high and bright that they nearly blend into the sky. In these same fields the young Ung children were taught to work as hard as adults. They learned to steal food at night in order to survive periods of near-starvation.

Loung knew even as a child how fortunate she was to have a caring family, but she didn’t know how easy she could lose this: “I rest my head on his chest and think how lucky I am to have such a father. I know Pa loves me.” After losing her family, Loung also loses much of her childhood innocence: “I cried silent tears for my family, my loneliness, and my constant hunger.”

As the title suggests, the Khmer Rouge soldiers first came for Loung’s father before the rest of her family. Although his fate is unknown, 14,000 Cambodian citizens were taken to S-21 Prison to be interrogated and tortured before being murdered at the Choeung Ek Killing Fields. As I closed Ung’s book on my taxi ride between rural Cambodia and urban Phnom Penh, I knew I had to track the devastating journey many like Sem Im Ung took so that I could better understand where this haunting chapter of history took place.

I walked silently around the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide. Formerly Tuol Svay Pray High School before being converted to S-21, Tuol Sleng holds onto an eerie history lesson that is still not actually taught in Cambodian schools today. I was fortunate enough to meet with one of the only two living survivors of S-21 (the last five survivors have since passed away), who told me how passionately he feels about Cambodia’s history and how he wants these stories spread around the world.. Reaching into my purse to buy his book, I realized my wallet was gone. It could have fallen out anywhere in the museum grounds.

I walked to security to report the loss, but already knew in my gut that it was gone. A young, bored-looking Cambodian boy overheard me and jumped at the opportunity to help me look. When we agreed it was missing, we sat down on a bench and just relaxed. I told him I didn’t mind the loss too much—it was just a bit of bad luck. He turned to me quickly, but spoke to me slowly:

“No. In my culture, we have a belief. Losing your wallet is good luck. It reminds you that you haven’t lost your life. It’s just stuff.”

Sitting in front of his country’s most violent landmark, his words could not have resonated with me more. At the beginning of the day, we’re all not too different. We all just want to value our own lives and have them valued by others. A five year old girl during a civil war, a fifteen year old boy whose family has endured a nation of genocide, and a twenty five year old girl working to improve the livelihood of farmers who have survived: all three of us quite different, but our humanity connects us. Our desire to tell stories, and to value and enhance the lives of others.

Through her memoir, Loung Ung brings you to Cambodia’s bustling cities and quiet, colorful countryside. Cambodia, a nation shaped by a complicated recent history, is home to a few million people who are probably just like you at the beginning of the day, but may be completely different at the end. As they say in Cambodia, “it’s same-same but different.”

Katie Steinharter lives in Denver, Colorado but finds herself at home all around the world. She recently spent three months traveling through Southeast Asia and Australia, helping social enterprises and NGOs develop strategic marketing plans. Katie loves to snowboard, learn new languages, and find her way around a new city by going for a run. She taught herself to read before going to preschool, and her father taught her to love reading before she got to kindergarten. When she’s not traveling, you may find her at the local bookstore or just laying on a hammock in the backyard of her parents’ house in Maine.

Main page image by ND Strupler

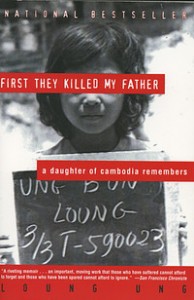

Purchase the book featured in this post here: First They Killed My Father by Loung Ung on Amazon.com

3 comments

I love the way your wove your own experiences within review of this book. Even without picking up a copy, I feel like I’ve learned more about the Cambodian experience from within and from outside.

“The word for green in Khmer is also the word for blue, and if you walk through a big rice field you can understand why. The rice straws grow so high and bright that they nearly blend into the sky.” That is just beautiful.