by Katherine Mclaughlin

I’m from Indianapolis, but when I turned 18 I moved away. I wanted to attend college and study writing in the most vibrant, cultured place I could think of: New York City. Brooklyn welcomed me with open arms, and since moving here I’m pretty much the same. I function as normal, but I’ll always be a Midwest Transplant. Like my hair I tried to dye blonde, roots never change. My hair is brown and my home is Indiana.

I think our hometowns are a little like third parents. They raise us, they make us. Like family, you don’t choose them. Everyone from there becomes a brother or a sister. You’re not close with every person, but you’re connected to each one.

The son of an architect, but the child of Indianapolis, Kurt Vonnegut is one of the most respected and influential authors of our time. He’s famous for his minimalistic and humorous writing, and often symbolic commentary on the world in which we live. During his life, he published 14 novels, three short story collections, and five works of non-fiction. Up until this past December, I hadn’t read any of them.

When I was home for a break from school I found a copy of Kurt’s fourth novel, Cat’s Cradle, in my family’s mid-century modern home. I often feel like I don’t fully understand my heritage, and Kurt Vonnegut seems to be one of the proudest and most knowledgeable members of the Hoosier Clan. I thought if I read his novel and visited places that were important to him, maybe I could learn something about myself, too. It would be like rummaging through a dusty attic, discovering family stories and secrets that have always been available if you’re only brave enough to go upstairs.Less than 10 pages into Cat’s Cradle, Indianapolis is mentioned. It’s an address on North Meridian Street. It’s coincidently two stoplights away from my home. The house where Newt’s sister supposedly lives would sit in the middle of the Meridian-Kessler neighborhood, one of the most coveted areas of Indianapolis. The streets are lined with 20th-century mansions so mysterious that every summer homeowners open their doors to curious neighbors as part of the Meridian-Kessler home tour. I had quite a few friends grow up inside these homes, and I used to walk dogs through the community when I was saving up for college.

I drove to the address where Angela Hoenikker lives with her husband, Harrison Conners. When I got to 4981 North Meridian Street all I discovered was an empty lot. Two beautiful homes stand to the left and right, but in the middle there is just a plot of grass hidden behind twig-branch curtains. I wonder if Kurt walked up and down Meridian searching for the perfect place for Angela to live. I wonder if he imagined what her house might have looked like standing between the two he saw in front of him. I wonder if he saw any of her real-life neighbors stepping outside to water their plants or get the mail.

The more I read about Angela, the more her would-be house made sense. Angela is the caregiver of the family, obsessed with the perfect image of the Hoenikker name. She uses her portion of Ice-Nine to marry a man who would not have fallen for her otherwise and passes it off as a happy life. She insists her father be portrayed “like a saint” in The Day The World Ended, “because that’s what he was”. A house on Meridian is a sign of stature, wealth, and cultural prominence – at least to those who live in them.

I’ve noticed residents tend to be prouder of where their home stands than passersby would be envious. Angela would be the type of person to carry pride that holds no weight outside of Interstate 465 that defines the city limits. This information isn’t given freely in the novel, but it’s something you understand if you grow up here, like family dynamics you only get by living in them.

In downtown Indianapolis, on the corner of Indiana Ave across from the Madame Walker theater sits a small, three-story building with a wrap-around balcony that houses the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library. About 100 pages into Cat’s Cradle I drove down there to visit.

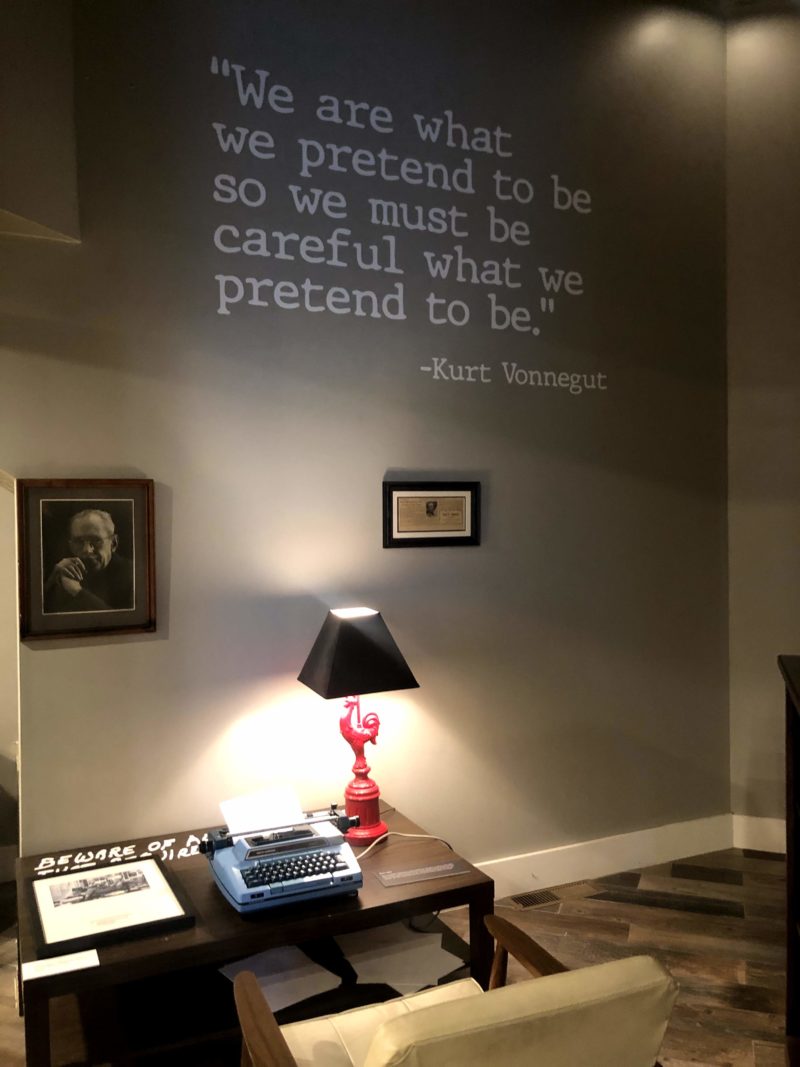

The museum is small, it only has 3 floors and I got a well-rounded experience in about an hour. The first floor displayed the “Freedom of Speech” exhibit and a replica of Kurt’s study, the second the “State of Indiana” room, and the third is a Slaughterhouse 5 showcase.

“We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful what we pretend to be” was written above the replica of his desk. Kurt had carved the words “be careful of all enterprises that require new clothes” into the wood that held a sky-blue typewriter and a red, rooster lamp. On the wall adjacent to his workspace were framed rejection letters. One plainly stated “I do not feel that you can write a short story which would be appealing to any of our regular markets” and another “I honestly think this Vonnegut would confuse our readers”. While I don’t know for sure, I can only imagine and hope they were framed next to his real desk as well.

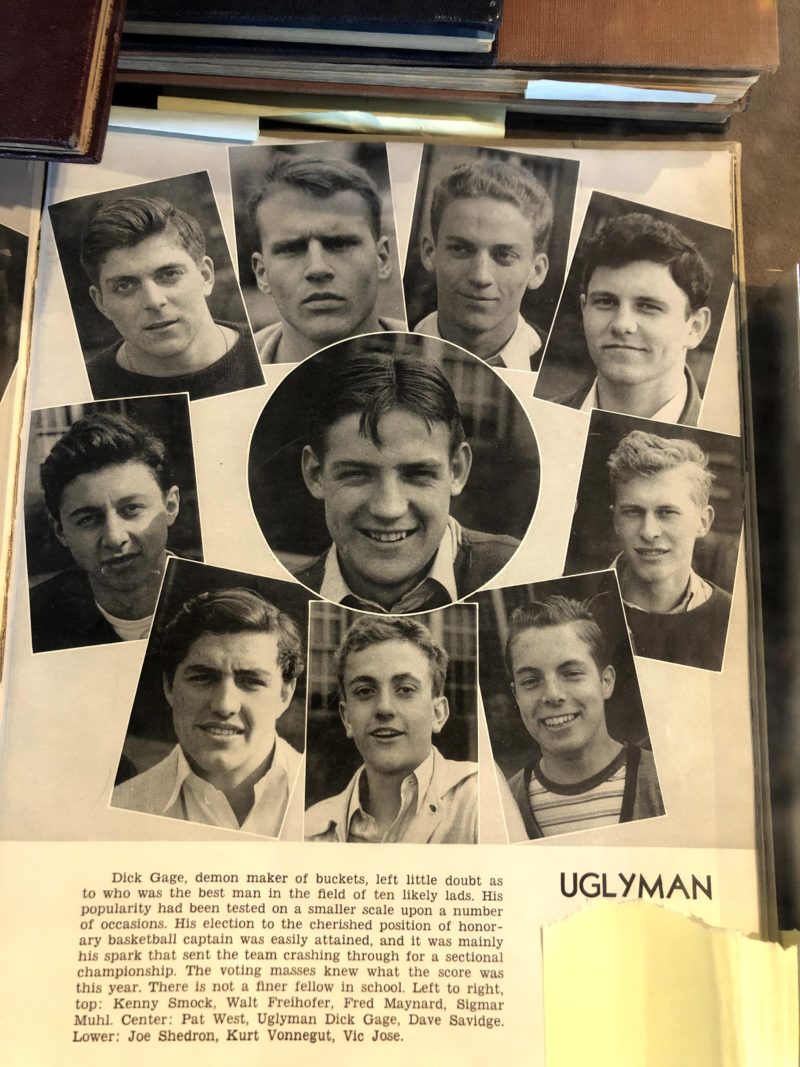

Upstairs, in the “State of Indiana” room, was all the evidence you would need to connect Kurt Vonnegut Jr to the Hoosier State. In a glass case in the center of the room was a copy of “The Annual”, Shortridge High School’s yearbook. It was flipped open to a page with Kurt and (presumably) his friends. It’s always strange to see who people were before they became the people we know. My grandpa went to Shortridge and graduated about 10 years after Kurt. For me, this high school on 34th and Meridian was just a large school that mine sometimes played in sports. A few days later when I visited it I learned it’s the oldest public high school in the state of Indiana and the original superintendent fought for education for black children. I guess there are still some hidden stories in my family’s past that I would gladly listen to again and again.

On the wall across from the glass case, was a framed letter Kurt wrote to an incoming Indiana University student. He said he did indeed consider himself “lucky to have grown up in Indianapolis” and that “there was a lot of really great stuff to think about”.

I have to agree with Kurt. Children of Indianapolis live a landlocked life. We don’t have the opportunity to get used to mountains or oceans. We don’t live in a big city or a small town. There’s no Disneyland to get bored of or monuments to take for granted. Indianapolis is perfectly neutral, a level playing field. A bit of this, a bit of that. You can dream of better and you can appreciate givens. It leaves the opportunity to still find excitement in everything, wonder in the unknown, and become the perfect runway for thoughts to take flight. That leaves quite a lot to think about.

The last floor of the museum was a Slaughterhouse 5 exhibition, I haven’t read the book yet. I’ll save a reflection on that for another time.

“Nobody has to be ashamed of being a Hoosier” Hazel Crosby said on page 64. “You can’t go anywhere a Hoosier hasn’t made his mark”. Those words rang in my head as I parked my car on the side of Illinois St, in front of a house marked 4401. When Kurt lived there it was 4365. It stands in the Butler-Tarkington neighborhood, about 9-10 miles from downtown Indianapolis. It’s less than 2 miles away from Shortridge High School, and a half a mile away from my childhood home at 256 Buckingham Drive.

Kurt’s childhood home is three stories, red brick, and finished with white trim. It has large windows and, unlike other homes on the block, the front door does not face the street. For privacy reasons, I did not get super close to the home or spend too much time loitering around the yard. Kurt Vonnegut Senior built the home for his family in 1923, apparently in the entry door window is the letter “V” with “K” and “E” (for Kurt and Edith) wrapped around it. The house is a good size, and probably quite big for when it was first built. A street I’d driven down a million times was suddenly much more interesting. It’s funny how a new destination can do that.

One of the last places I visited, right as Ice-Nine was destroying San Lorenzo, was a mural of Kurt on Massachusetts Avenue. On the wall, he’s wearing a red sweater with a blue button-up underneath. He has on a long, tan coat and stands 38 feet tall. He looks over Indianapolis like an older brother. He looks humorous and disobedient. He looks amused. He looks sad. He was painted because Indianapolis is proud to have raised him, he stands tall because he was proud to call Indianapolis home.

“Whenever I meet a young Hoosier, I tell them ‘You call me mom’”, said Hazel. Maybe it’s just an Indiana thing to assume we’re all related, I don’t know. This week I visited a lot, a museum, a school, a house, and a wall. Five points I thought would somehow connect a place, a man, myself, and a family.

Maybe there is no conclusion, no epiphany, no meaning. But for the first time, I saw places I’d only ever looked at and listened to stories I’d only ever heard. When I piece together everything I learned and visited this week it’s just a crisscross of lines and moments, places and chances tied together by time. There’s no cat and there’s no cradle, but I’m okay with that. I am a child of Indianapolis, and for now, that is enough.

Katherine McLaughlin is an NYC based writer originally from Indianapolis. She lives in Brooklyn and studies at The New School. Primarily interested in creating human connection, she values the power of words that can create the effect. To stay up to date with her writing you can follow her on instagram @mclaughlinkate or visit her website www.bykatherinemclaughlin.com.

Katherine McLaughlin is an NYC based writer originally from Indianapolis. She lives in Brooklyn and studies at The New School. Primarily interested in creating human connection, she values the power of words that can create the effect. To stay up to date with her writing you can follow her on instagram @mclaughlinkate or visit her website www.bykatherinemclaughlin.com.