By James Michael Dorsey

It was 1973 when I unexpectedly landed a job as a letter carrier in the idyllic seaside community of Pacific Palisades, California. After several previous dead-end jobs, it was more money than I had ever made, and being a rudderless young man without goals or much ambition, I felt I had landed in a fat city. My job at the time was a now defunct postal service known as “special deliveries.” Whenever a letter or parcel arrived at the office with that designation, I was immediately dispatched to the address, sometimes delivering two dozen such pieces a day, seven days a week. These deliveries all required a signature from the person they were addressed to. No proxy was allowed to sign for them. I quickly learned that the city I worked in had an over-abundance of wealthy celebrities, mainly from the motion picture and entertainment industries, and the flow of special deliveries kept me hustling.

I also found out that mailmen had much in common with bartenders and priests in that everyone wants to talk to you. It makes sense when you consider that mail carriers are the last people left who come to your home on a daily basis to provide a service. Suddenly this young man from the wrong side of the tracks was having coffee with John Forsythe at the height of his popularity on Dynasty, and helping to chase down Rod Serlings’ golden retriever that bolted when he opened his door to me. For that I was rewarded with a reading of his latest script for the “Twilight Zone.” I had long chats with Walter Matthau, and Mel Blanc spoke to me in the voice of Bugs Bunny. It was common to see Michael Keaton having coffee at the Bay Pharmacy or to bump into Vin Scully shopping at Vons. Adam West, who was Batman at the time, allowed me to try on his cowl. Tom Hanks actually stopped his car to chat with me the morning that he won his Oscar for his role in the movie, “Philadelphia.” I was totally star struck in those days and couldn’t believe I had a job that put me in such proximity.

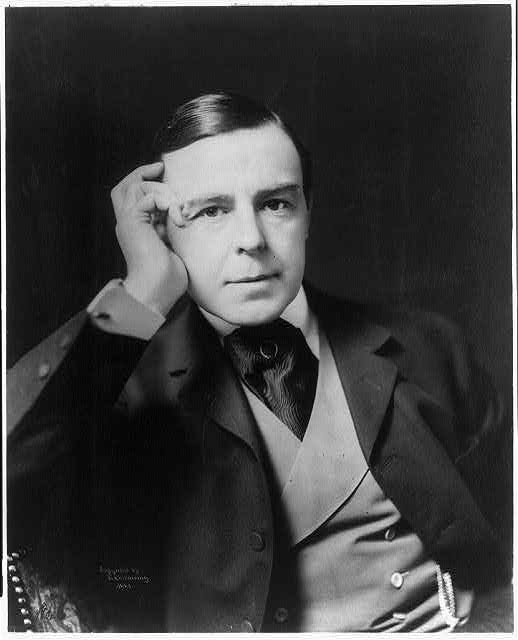

One day a letter arrived addressed to Henry Miller on Ocampo Drive. At the time I knew he was a writer but I knew little else about him.

The door opened and before I could get a word out I was confronted by a six foot Amazonian beauty, clad only in bra and panties, who locked me in a bear hug saying, “Hi, I’m Twinka, and you’re cute!” With that she took me by the hand and practically dragged me inside. I remember the house being filled with watercolor paintings that it turned out were all the work of Mr. Miller. She ushered me to the bedroom where there, in an enormous bed, sat pajama-clad, 82-year-old Henry Miller, surrounded by an explosion of papers and books. At my entrance, he looked up, over the top of his glasses and said simply, “Come in young man and have a seat,” patting the bed next to him.

I grew up in a house without books. My parents were children of the great depression and both left school at an early age to work in order to keep their families afloat. We did not read; we watched television. They were simple people who loved me dearly but whose only real advice was to graduate from high school and get a steady job. We lived in a working class town where repetition was a way of life. College was never an option for me and I had no life plan. I fled my small town by enlisting in the army and was twenty years old when out of boredom, I read the first book not required of me in school; Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood.” I read it in one sitting, unable to put it down. While I did not understand the groundbreaking techniques that made it so successful, I knew it was special, and it started me reading, although my taste at the time was limited to science fiction or thriller novels.

So, I was totally unprepared for the work of Henry Miller. His semi-autobiographical novels such as Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn were banned in the United States and England; considered pornography by many. At the time, I certainly did not comprehend his blending of social criticism, philosophy, free association, and explicit sexual language that had made him the standard bearer for such new writers as Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg.

I was even less aware that the lingerie-clad Twinka, who was living with Miller at the time, served as both assistant and cook, and was the first born daughter of internationally acclaimed painter Wayne Thiebaud. That aside, she was in great demand as a model for some of the finest photographers of the day. She was the first model to appear full frontal nude in LIFE magazine, and many photos of her are now in major museums and private collections including Florence’s Uffizi Palace, and New York’s Museum of Modern Art. She also modeled for her father and one of his paintings of her was sold for $1.8 million dollars. If ever someone was out of place in a particular situation, I was at that time. (see Miller and Tinka together here)

I did not know that Miller would spend much of the final 17 years of his life in that house, hosting dinner parties almost nightly for the literati of his time. I learned long afterwards that he was a spellbinding story teller and that Twinka recorded many of these conversations in her journal. To this she mixed in the wit and witticisms she had overheard at the house from the beautiful people of the day and published it all in a book called “Reflections.” That was the environment that I naively wandered into never thinking it would become a regular event. Why was I allowed into the inter sanctum?

Naturally my first impulse at being invited to share bed space with an older man set off my inner alarm, but because there were several other people in the house at any given time I felt strangely safe, not to mention curious. I warily sat on the end of the bed and Henry handed me a page to read that he had apparently been working on and fixed his gaze upon me as I read it. When I finished with his profanity laced tome he asked me what I thought of it and all I could say was that I had never read anything like it; that made him laugh.

And so that first visit turned into many as the special deliveries kept coming. Each time was a repeat of the first with little variation that became, over the weeks, almost a ritual. Twinka would let me in, always with a big hug before ushering me into Henry’s bedroom where we would have coffee. Apparently he lived and worked, much like his contemporary, Hugh Hefner, in bed, 24/7. After several weeks of such visits I had never seen him standing. Even though this man was known for foul language and sexual overtones in his books, he never approached me in that manner. I never heard him curse. All he ever wanted was for me to read what he was writing and give him my thoughts, which at the time were quite minimal not to mention, naive. Sometimes he dramatically read his work to me in hopes of getting more of a reaction. I bought a copy of Tropic of Cancer thinking I might be able to hold my own in conversation after reading it but I only got through the first few pages. His work was over my head.

He never pressed me for comments or explained what he was trying to do. After reading his latest offerings there were often great lapses in the conversation when he would just stare blankly, having removed himself to another place. Sometimes he would shush me with a finger to his mouth and listen to the gossips coming from other parts of the house. That seemed to amuse him greatly. He told me stories about his days in Paris, a city that I would not visit for several more years, and there were intimate stories about his liaisons with Anais Nin of whom I then had no knowledge. His stories referenced Picasso and James Joyce, Jean Cocteau and Sylvia Beach. He seemed to know everyone and made constant references to the rich and famous by their first names, often losing me in the telling. He had a real need to talk. The house was always full of people coming and going, some celebrities in their own right, others, the usual hangers on who attached themselves to the rich and famous. With telephones ringing and Twinka flitting about like a worker bee, my visits were a moment’s calm in the storm that was his life.

Eventually I got my own mail route and that ended our visits. When I told Henry I was leaving he said I would be missed and that I should stop by anytime but I never did so again. I simply felt uneasy about dropping by, realizing I was not an actual friend, but more like a temporary respite. I also thought long and hard about why such an accomplished person would want to share their intimate work with someone who had no idea what they were reading. In the end I decided that Henry liked me because I was straightforward and uncomplicated. I was not a voice from the crowd that considered him a pariah. I certainly never criticized or challenged him. I was just a guy from the street he could visit with to escape the turmoil of his normal daily life. I only recall ever asking him one serious question about his work and that was why did he use such foul language? “Because it gets peoples’ attention,” was his reply. The last thing he said to me was, “You should read Bukowski. He started at the Post Office also;” giving me one more name that I did not know, but would come to know shortly.

If nothing else, those visits expanded my reading. I devoured the modern beats that knelt at Henry’s altar, Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs, and set out on a literary voyage of discovery that took me from Twain, to Hemingway, and finally to Chatwin, Millman, Cahill, and Lopez. They were the ones that enchanted and inspired me. That chance encounter of delivering that first letter opened a magical new world to me.

It took a half century before I owned the courage to put my own thoughts on paper. I had always been a traveler so I began to write about what I knew best. It took a while for me to learn that travel writing was its own genre. I just felt the need to write.

Two decades later, I can claim more personal success as a travel writer than I ever dreamed of, especially for one who came to the craft so late in life. I don’t believe that meeting Henry Miller had any direct bearing on my becoming a writer, but when I consider all things, perhaps it was the first baby step that put me on that path.

I am sure that if Henry knew what I would become he would have commented with a profane expletive, at least on paper. I have since read Charles Bukowski but still have never read any of Henry Miller’s books

James Michael Dorsey is an award winning author and explorer, who has spent two decades researching remote cultures in 52 countries.He has written for UNITED AIRLINES, PERCEPTIVE TRAVEL, COLLIERS, The CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR, LONELY PLANET, LOS ANGELES TIMES, BBC WILDLIFE, BBC TRAVEL, HIDDEN COMPASS, PANORAMA, NATURAL HISTORY, plus several African magazines. He is a foreign correspondent for CAMERAPIX INTERNATIONAL and a travel consultant to BROWN & HUDSON of London. His latest book, “BABOONS FOR LUNCH,” and his previous book, “VANISHING TALES FROM ANCIENT TRAILS,” are available on AMAZON. His stories have appeared in 20 travel anthologies. He has won 22 SOLAS AWARD categories from TRAVELRS TALES and is a contributor to their “BEST TRAVEL WRITING, VOLUMES 10, and 11, plus the LONELY PLANET LITERARY ANTHOLOGY.” He is a retired fellow of the Explorers Club and member emeritus of the Adventurers Club.