By Suzanne Adam

The death of Gabriel García Márquez prompted me to reread his Nobel-winning One Hundred Years of Solitude,“Cien Años de Soledad” in Spanish—the epic novel, which traces the Buendía family over one hundred years. I’d read it in English long ago while a student in Berkeley, not knowing then that soon I’d be living as a Peace Corps volunteer not far from Márquez’s childhood town of Aracataca, which in his imagination became the mythical town of Macondo. Rereading the novel now fifty years after my Peace Corps posting in Barranquilla, Colombia, García Márquez’s wild, extravagant tale stirred up old memories entangled in cobwebs. Half-forgotten smells, flavors, and feelings came alive.

The city of Barranquilla, in northern Colombia, is situated across the Magdalena River from the province where Aracataca/Macondo lies. My home for two years greeted me with a blast of heat, humidity, squadrons of mosquitoes, decaying buildings, and the stench of rot and mildew. The marginal barrios where I lived and worked as a community organizer had grown up on the periphery of the city on eroded slopes of red earth, sparsely populated with shrubs and spindly trees. My initial reaction was shock. I had always been a lover of the natural world, but how was I to love that place? The harsh extremes of climate and geography required that I make severe inner adjustments. As author Kathleen Norris said of the Dakota landscape, “[T]he region requires you wrestle with it before it bestows a blessing.” So I wrestled.

It took little imagination for the phantasmal tales from Macondo to remind me of the dust devils that swirled along the unpaved barrio roads in the dry season, following the garish, multicolored buses in which I’d sit, wedged among brown bodies, lurching in counterpoint to meringue music from Radio Caracol, red fringes and saints’ images swaying over the windshield. Months of heavy rains followed, renewing at night the wonderful, deafening chorus of frogs, ensconced in pools of gluey mud that clung to my shoes, while the god of thunder prepared his drums to shake my house to its foundations. Giant cockroaches, antennae waving as they crept down my bedroom walls, became the monsters of my nightmares. Maybe they were the bearers of the insomnia that afflicted the people of Macondo. For an uninterrupted night’s sleep, I resorted to sleeping under a mosquito net.

My barrio neighbors were migrants to the city, rootless, as was the first generation of the Buendía family. Squatters, my neighbors erected feeble, temporary shacks that became permanent with dirt floors, wobbly furniture, bare lightbulbs overhead, walls decorated with gaudy calendars, and black-and-white daguerreotypes of solemn-faced grandparents whose bones lay buried in some country cemetery. As in Macondo, the barrio streets had no names, locations indicated by landmarks—the street of the palo blanco or the ceibo tree. I felt toughened and proud that I had learned to maneuver my way through the labyrinth of winding barrio roads, even at night.

Macondo-like country customs spilled over into those barrios. Straight-backed mulattas passed by my house, balancing tin bowls on their heads, calling “aguacate” (avocado)” or “mango”. One evening I watched a group of men playing their flutelike gaitas while the women danced the cumbia in a circle, their raised hands holding lit candles. The local men wore the black-and-beige straw campesino hats for protection from the searing sun. Boys on burros, laden with boxes of charcoal, sold the fuel for kitchen fires. From the doorway of my cinder-block house, I bought water from two boys driving a burro-drawn cart, loaded with large oil drums fitted with spigots. I learned to live with the bare necessities and have cherished simple living ever since. The Buendías’ battle with the mildew and comejénes (termites) that chewed their way through the family’s furniture and walls brought back to me the stench of the mold that stained the pages of my books and the comejénes that carved tunnels through my shabby bedroom cabinet, scattering trails of sawdust among my clothes.

My neighbors would have fit comfortably into Márquez’s novel. Many a morning, I waved over my backyard wall to Delia, gray-haired and toothless, talking loudly to herself nonstop, her complaints directed to anyone within hearing distance, as she washed clothes in an outdoor tub. It wouldn’t have surprised me if one evening she’d careened off into the sky, cackling, aboard a broomstick.

Dominga, my cigar-smoking housemate and dear friend, kept me laughing even on the hardest days. Dressed in her white housecoat, closed at the top with a safety pin, she provided affection and humor that acted as my antidote to the cockroaches, the stifling humidity, and Delia’s gloomy vibes. Illiterate, single mother and grandmother of five, her feet firmly planted on the earth, Dominga was my Ursula, the Buendía family matriarch. She grounded me in the coastal ways, sharing her opinions and local gossip, rife with rivalries, rumors, superstitions, mal de ojo (the evil eye), and mysterious aires (drafts). Her brown face crinkled up like a large prune, she conversed with her two parrots perched on a kitchen rafter: “Lorito, lorito real, para la España no, sino pa’Portugal.” (Little parrot, royal parrot, not to Spain, but to Portugal.)

But, the dampness, the mildew, the malnourished children, the illnesses and deaths were not products of a writer’s imagination. Life in the barrio was precarious and fragile, yet I discovered magic in the music, the smiles, and the generosity that flourished in that inhospitable landscape. Like a phantom from the past, I wanted to return—to taste fried plantains again, hear the wild chorus of nighttime frogs, and face that extreme climate and landscape that revealed to me my inner strength. Names and faces surfaced from the depths of memory—the blessings bestowed on me: Dominga, Ana, Anselmo, Juan, Petra. Would any remember me, or would they not know me—just as Amaranta Ursula and Aureliano Buendía failed to recognize the vagrant uncle who appeared at their door, because no one was left to tell them the old stories?

I did return to Barranquilla and my old barrio, most recently in November, 2019. People did remember me. I sat on her porch and visited with ailing Agripina whom I’d known as a young teenager. Though many of my old friends were no longer there, like Petra, I met her daughter, Rosa, who invited me into her home. “You look just like your mother!” I told her. She and her family posed for a photo with me. I also reminisced with Juan, whose father had presided the barrio committee building the health center. It was encouraging to see that he lived in a solid house, not the wooden shack where he’d grown up.

As planned, I met up with Marjory, a Peace Corps friend, now living in Cartagena. Together we explored Caribbean beaches, Cartagena’s colonial, walled city streets, the coastal town of Santa Marta and nearby Tayrona National Park. As in Peace Corps days of old, my friend and I traveled by any means of transportation available: local bus, 1980’s Trooper jeep, pickup truck, carro-taxi, bici-taxi.

But it was in Aracataca, birthplace of Gabriel García Marquez (fondly known as Gabo) where, on the wings of imagination, we traveled the furthest, back in time to the fantastical town of Macondo. The bus ride to Aracataca was lined with banana plantations as if foreshadowing the setting for “One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

Bici-taxi was the way to find a place for lunch in Aracataca. From there, we walked along well-kept streets, passing a wall painted with a likeness of the author and a flock of hamburgers with wings, announcing “Gabo’s Comida Rapida,” (Fast Food). I didn’t recall that his magical realism conjured up flying hamburgers.

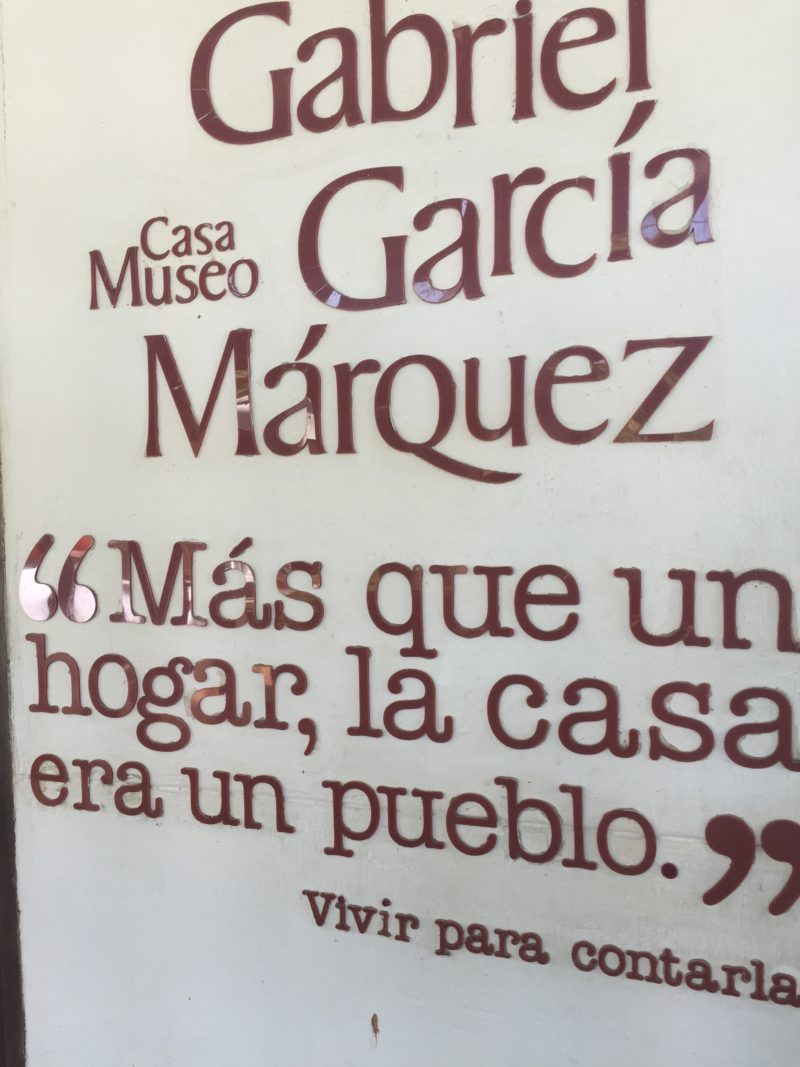

We arrived at his museum, a series of replica rooms located on the plot of land where only one original structure remains. His words written on an outside wall set the tone for this visit. “More than a home, the house was a pueblo.” In the first room, his grandfather’s study, I read: “The move to Aracataca was seen by my grandparents as a journey into forgetting.” There were very few visitors. We walked through the silent rooms of memorabilia: his grandfather’s desk, Gabo’s childhood bed, family sepia portraits. Nostalgia permeated every space. Along the walls were quotes from Marquéz’ books, which gave me the sensation that he was right there beside me. He said: “There is not a line in one of my books that does not have its origin in my childhood.” In the kitchen filled with old utensils, I read: Nothing was eaten in the house that was not seasoned in the broth of longing. In those rooms I was a visitor to the past where the imagination that created the town of Macondo found its early inspiration.

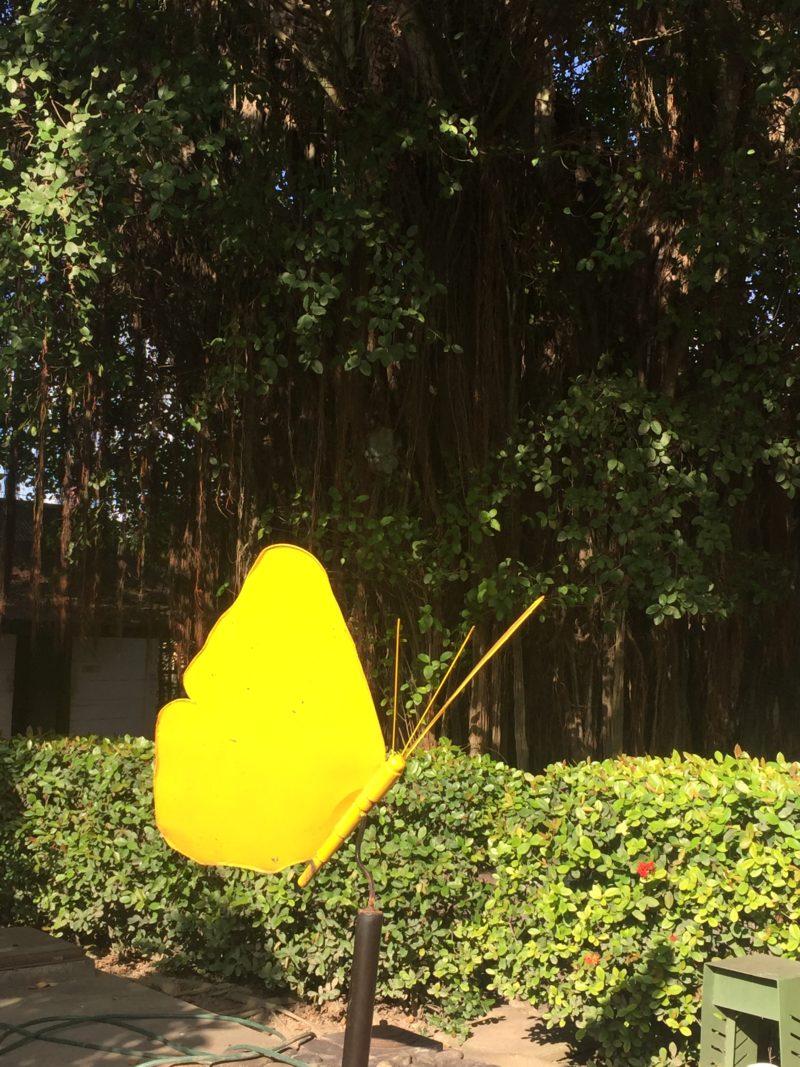

In a back patio grew a majestic rubber tree, its thick tangle of roots and lianas reaching high above me. It must have intrigued Gabo as a child. A bright flash of color fluttered by. Before I could say “mariposa!” it came to rest on one of the gnarled tree roots, but I saw no bright colors, rather a large, splendidly camouflaged, day-flying moth. I thought of the clouds of yellow butterflies that populated his novel and imagined Gabo’s delighted eyes observing the garden creatures.

Aboard another bici-taxi, we passed colorful murals lining the canal coursing through town and, finally, arrived at the town’s entrance to catch the return bus. There I posed in front of bright, giant letters announcing “Aracataca” and “Macondo”. The townspeople had opted for a double name for their town. I sent this photo to my family with the caption “Greetings from Macondo.”

This return trip to the Colombian coast required that I wrestle once again with the searing heat, the humidity, the discomforts of rudimentary transportation. But, oh the blessings bestowed upon me by my old barrio friends. Then in Aracataca/Macondo I let myself fall under Gabriel García’s spell, feeling his presence everywhere, sensing I could permeate myself with some of his magic. Did he send that lovely day moth to delight me? I like to think so.

Suanne Adam is a California native who served in the Peace Corps in Colombia before moving to Santiago, Chile in 1972 to marry her boyfriend, Santiago. She explores how this experience shaped her life in her 2015 memoir Marrying Santiago. In 2019, She Writes Press published her second memoir Notes From the Bottom of the World: A Life in Chile. Before turning to writing, Adam worked as a teacher of children with learning disabilities. A member of Santiago Writers, her essays have been published in The Christian Science Monitor, California Magazine, the Marin Independent Journal, Nature Writing and Persimmon Tree. She blogs at tarweedspirit.blogspot.com.