By Lewis Waller

After the first travel guide to Britain was published in 1772, Thomas West, a Scottish Jesuit, published his own guide to the English Lake District. West, one of the first writers of a new Picturesque Movement, guided the traveller to ‘viewing stations’ that rewarded the most balanced, scenic, and picturesque – a new word for the time – points of view. Painters and sketchers would use these guides to produce quick works for the newly monied bourgeois class.

Aristocratic Englishmen were, of course, supposed to be explorers, adventurers, and colonisers, but ‘The Grand Tour’ – a rite of passage for young noblemen – had traditionally meant exploring the great ancient civilizations of Europe rather than pedestrian local sights. Those first British travel guides contained a difference message: there was something important at home, too.

This was a revolutionary shift in attitudes. In the preceding decades, Britain’s ‘useless’ wilderness was usually described in disparaging terms. For the author of Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe, for example, the mountains of Cumbria had an ‘unhospitable terror in them’ while the fields were ‘all barren and wild, of no use or advantage either to man or beast.’ Another travel writer, Celia Fiennes, called them ‘the desert and barren rocky hills.’ The poet John Dalton wrote that the horrors of the landscape were alarming.

The attitude was common throughout Europe. James Howell described the Pyrenees as ‘not so high and hideous as the alps’ but as ‘uncouth, huge, monstrous excrescences of Nature, bearing nothing but craggy stones.’ These appraisals are a sharp reminder of how our attitudes toward the things we assume to be ‘natural’ are, in fact, shaped by our cultural perspective.

The English Lake District – sequestered from the rest of the country in an almost otherworldly enclave – has plenty to remind us of the historicity of our cultural lens. Camping in quiet Thirlspot, under the foot of England’s third highest peak, Helvellyn, the calm waters of Thirlmere look like a glistening emblem of the natural world. Thirlmere is not exactly ‘natural’ though. It is a manmade reservoir hiding a drowned village in its depths. This, of course, does not detract from the pleasure of the view. In fact, it adds something. Reading about the battles that the residents fought against a reservoir being built to satiate the thirsty workers of Manchester’s industrial revolution yields a deeper satisfaction, providing a more human perception to a natural view. The poet William Wordsworth, who knew that we experience nature, culture, and psychology as a synthesis, wrote that ‘minds that have nothing to confer find little to perceive.’

The Romantic Movement that Wordsworth was a central figure of is difficult to define. Loosely, the diverse group of European writers were critical to an Enlightenment project that privileged reason and logic over emotion. They believed that it was not possible to understand human nature by studying people under a microscope, categorising them, and theorising about their calculable and universal characteristics. Instead, you had to meet them, experience each other’s passions and interests, become absorbed in their ever-shifting traits and qualities; this was reflected both externally, in the natural world, and internally, within our own psyches. In short, fluctuating sentiments were just as important as universal mathematics, science, and logic.

We all live our lives with the support of logical thinking; even making a cup of coffee in the morning is an act of logic, with one action following the other. But it’s not often that we admit that the intuitions, feelings and motivations that guide the very foundations of our lives are not always comprehensible. We feel that we want to become doctors, intuit that we would like to go out for Thai food, desire to visit this beach or that mountain.

From the routine of our predictable urban environments, though, we find it difficult to reflect on how our lives are guided by phenomena that are often outside of our own logical comprehension, and more importantly, reflect upon what this means. Wordsworth wrote that the ‘perpetual whirl’ of city life meant that the trivial objects around us were ‘melted and reduced to one identity, by differences that have no law, no meaning, and no end.’

There are some simple Romantic solutions. The Romantics believed that our own ‘nature’ varies and shifts as circumstances do, feelings morph and adapt, values are reborn to circumstance. This is mirrored in nature, in the fluctuating weather patterns and the change of the seasons, the way clouds feed streams and rivers satiate plants and grass sustains animal life. In nature, your heart rate adapts as you hike, your body temperature reacts to the weather, you find a natural rhythm and symbiosis not found in city life. New sensations – ‘a thousand blended notes’, as Wordsworth wrote – hit the eyes, ears, and skin. Here is the perfect time to reflect.

Thomas De Quincey suggested that Wordsworth had walked some 185,000 miles throughout his life. This was unusual not because of the lack of modern transport, but because exploring in this way was an oddity even for the time. When the German pastor Karl Moritz committed to walk to Oxford, for example, and sat down to rest in the shade, he wrote, ‘those who rode, or drove, past me, stared at me with astonishment, and made many significant gestures, as if they thought my head deranged.’

Today, we know the restorative powers of walking in nature only through the revolution in thinking the Romantics started. Hiking the relatively forgiving paths to the summit of Helvellyn, for example, was a reminder that these sorts of excursions often spark deeper conversation about the rhythms of life, of what we’re doing, why we’re doing it, and where we might want to be in the future.

In his guide to the lakes Wordsworth asks the reader to imagine their station is a cloud someway between Great Gavel and Scarfell. From there one can see around eight valleys, ‘diverging from the point, on which we are supposed to stand, like spokes from the nave of a wheel.’ The peak of Helvellyn and the panorama of what is likely to be one of the best views in the country is as close to Wordsworth’s ‘station’ as can be gotten. The wooded paths though the crags and fells are rich in ecological diversity and devoid of cell phone signals. The perfect environment for reflection.

In the late eighteenth century, the Industrial Revolution was slowly creaking and whistling into the juggernaut it would become. The radicalism and social tension that culminated in the French Revolution was a protest against tradition, aristocracy, complacency, and privilege. Some might see parallels today.

The early Romantics in England – Blake, Wordsworth, and Coleridge, in particular – believed that the answer was not a political revolution, but a cultural one. In Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth and Coleridge eschewed high intellect and instead emphasised the ordinary, the mundane, and the sometimes ugly. The ground-breaking collection gave a voice to the voiceless in much the same way that modern soaps, dramas, or journalism does. It was intended to be culturally democratic, to make the problems of the ordinary lives of the marginalised difficult to ignore.

When we visited Wordsworth’s old home in Grasmere, Dove Cottage, Jeff Cowton, the curator and head of learning, told me that ‘Simon Lee the Old Huntsman’ was his favourite Wordsworth poem for this reason. The simple ballad tells the story of an elderly man, too frail to chop wood, who is helped by an empathetic stranger. In it we can see central Romantic themes: the ordinariness of the scene, the natural setting of wood chopping, the foregrounding of natural sentiment and emotion, and finally, a bittersweet mood that runs through the lines. It’s the thankfulness of Simon Lee that moves the narrator: ‘Alas! The gratitude of men, has oftener left me mourning.’

We also see this bittersweet tone in ‘Line Written in Early Spring’ when the narrator is ‘in that sweet mood when pleasant thoughts bring sad thoughts to the mind.’ For Wordsworth, in contrast to the ideal coherence of the Enlightenment Rationalists, contradiction is a necessary part of human nature. Not all things can be categorised, comprehended, and reasoned with. Sad thoughts are sometimes happy. Admirable values often have a dark underside.

In the same way nature helps us to find an equilibrium with the inevitable changes in life, reflecting on the contradictions inherent in our own emotions and values teaches us to better endure those changes, work with them, even welcome them. Romanticism means embracing the messiness of life rather than seeking an orderly, urban, or domesticated routine.

This was in stark contrast to the Enlightenment Rationalists of the time who believed that we could perfect the world if only we relied on our logic alone. Half a century later, the Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky would call this attitude a delicate ‘crystal palace of reason’. The narrator of his novella, Notes from Underground, knew he was ultimately irrational, he ‘could not become anything; neither good nor bad; neither a scoundrel nor an honest man; neither a hero nor an insect.’

The belief that everything does fit together logically is increasingly harder to defend in our divisive and emotionally driven political landscape. There is no better example of this than the optimism that the early internet was met with. In the nineties, the internet was going to bring a scientific and political utopia. Direct democracy could be established, everyone could contribute to the political process, and all would have access to the truth in an instant. With facts and data at the disposal of all, ignorance and disagreement would be moribund. Contention was to die an illogical death. This was ill-fated because, as the Romantics knew, while facts about physics might cohere, facts about human nature varied, were relative, were driven by passions and urges which often could not be aligned.

Technology, Smartphones, and the internet are always a means to an end, always subservient to our underlying human natures. Reason, as David Hume remarked, is the slave of the passions. I am sceptical, though, of the desire to simply switch off. Nature is not simply an escape. These moments should, instead, be a time to reflect on and reconfigure our attitudes to the logic of daily modern lives.

I don’t think any of this is revelatory. We all know it, deep down. But we only know it because of the Romantics and the tradition that they left us. They teach us that reflecting on base nature, emotions, values, and sentiments is not an ‘escape’ to a primordial Eden or a pre-societal ideal human experience, but a way to reinterpret and rebalance the vast contradictions we experience in life. We can be urbanites and nature-lovers, socialites and introverts, technophiles and ecologists; there is no single, logical way of living.

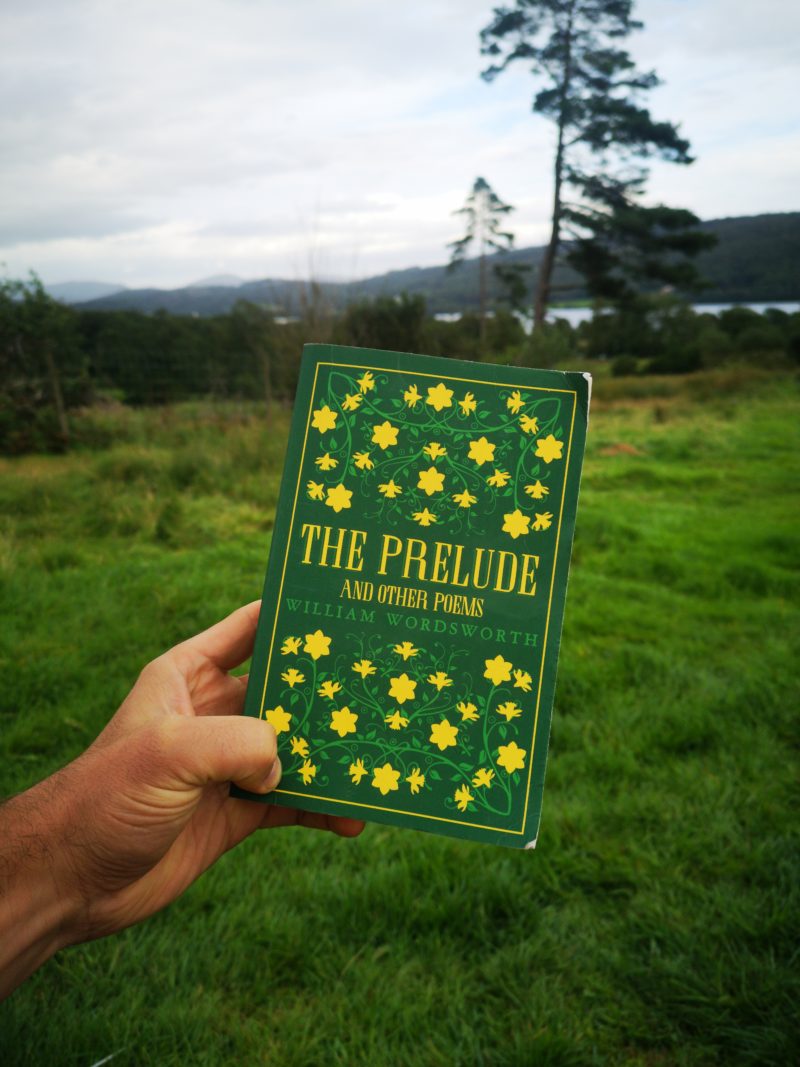

A trip to somewhere like the Lake District [insert your own Romantic landscape here] to read the Romantics and to reflect on their lessons is sublimely restorative. It was a reminder that books and their philosophies aren’t simply abstract. We should get out and read them where they’re meant to be read.

Lewis Waller is a History MA and Associate Lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London. He has a Youtube Channel on History, Philosophy, and Politics (Then & Now – https://www.youtube.com/c/then&now) with almost 90,000 subscribers. He recently made a short documentary on the Romantics and the Lake District which was made on a 10 day trip in August.