By Leslie Waugh

Ireland had long been on my list of places to visit, and after a fantastic two weeks in Iceland in July this year, my husband and I decided to go for it — still shaking off pandemic lockdown mode and embracing his 2020 retirement. I spent early August planning our three-week itinerary for September, before the tourist track largely shuts down. We had all the navigational tools we needed, in the form of Rick Steves’s guide to Ireland and cell phones with map apps. But what really oriented me to the Emerald Isle, across the Atlantic Ocean from our home in North Carolina, was a poem.

I first met Seamus Heaney’s “Postscript” in October 2014, courtesy of David Whyte. Whyte, of Irish and English parentage, recited his poetry and pieces by other writers to explore the “beautiful question” during a weekend workshop in Massachusetts, My early notes say: Asking a beautiful question can shape your identity. And, apropos of travel: A proper relationship with the horizon in your life may also mean a proper relationship with the ground. What is my relationship to the unknown? Or do I seek to replace it with the known?

The first poem Whyte recited was Heaney’s “Postscript”:

And some time make the time to drive out west

Into County Clare, along the Flaggy Shore,

In September or October, when the wind

And the light are working off each other

So that the ocean on one side is wild

With foam and glitter, and inland among stones

The surface of a slate-grey lake is lit

By the earthed lightning of a flock of swans,

Their feathers roughed and ruffling, white on white,

Their fully grown headstrong-looking heads

Tucked or cresting or busy underwater.

Useless to think you’ll park and capture it

More thoroughly. You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.

I was smitten. Four years later I would memorize “Postscript” and recite it at the end of a two-year yoga teacher training course, my heart having been repeatedly “blown open” through the physically and spiritually rigorous program. The poem had become like an internal compass that set things right when I felt lost, helping me rediscover my horizon. I frequently burst into tears at the closing lines, especially when reading the poem aloud, having been breathlessly swept away by the narrator’s voice in the first 11 lines, all the way to Ireland, and to a specific, unknown place. I love that the speaker is gently but directly inviting — imploring — the reader to do as they did, to follow their lead, if not literally then in spirit.

“Postscript” became like a treasure map, with the Flaggy Shore the X marking the spot where the poem’s riches lay buried — or, as described, out in the open for anyone to see. And by the way, I wondered as Whyte read, what is the Flaggy Shore?

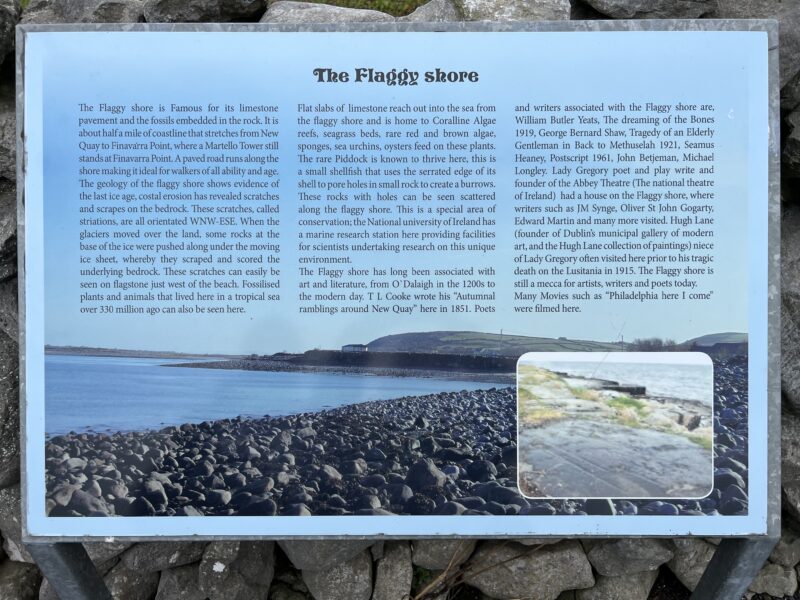

Heaney, who was born in Northern Ireland but settled as an adult in the Republic of Ireland, said “Postscript” was written quickly after a visit to the Flaggy Shore area in western Ireland. The shore, in the Burren region of northern County Clare, is roughly a half-mile stretch along Galway Bay from the village of New Quay to Finavarra Point. It takes its name from the limestone slabs that hug the waterfront and are used as floor flagstones.

Heaney is considered one of Ireland’s greatest poets, which is saying something since poetry is one of the country’s greatest contributions. He once said of “Postscript,” “There are some poems that feel like guarantees of your work to yourself. They leave you with a sensation of having been visited, and this was one of them.” In 1995, Heaney became the fourth Irish writer to receive the Nobel Prize for literature, joining George Bernard Shaw, William Butler Yeats and Samuel Beckett.

Our trail to the Flaggy Shore started when I found an Airbnb in New Quay while planning our trip — with “Flaggy Shore” actually in the listing. Yes, please! I built our trail around spending the next-to-last chunk of our time there, and lined up other ports of call. We started in Dublin and continued by rental car to Kilkenny, Kenmare, Portmagee, Dingle and then the Flaggy Shore. After five nights exploring “Postscript” country, we wrapped up our trip in the village of Furbogh, west of Galway and across the bay from New Quay.

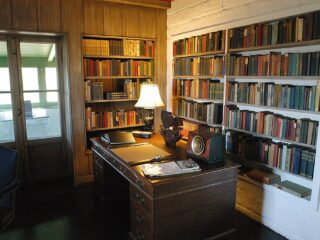

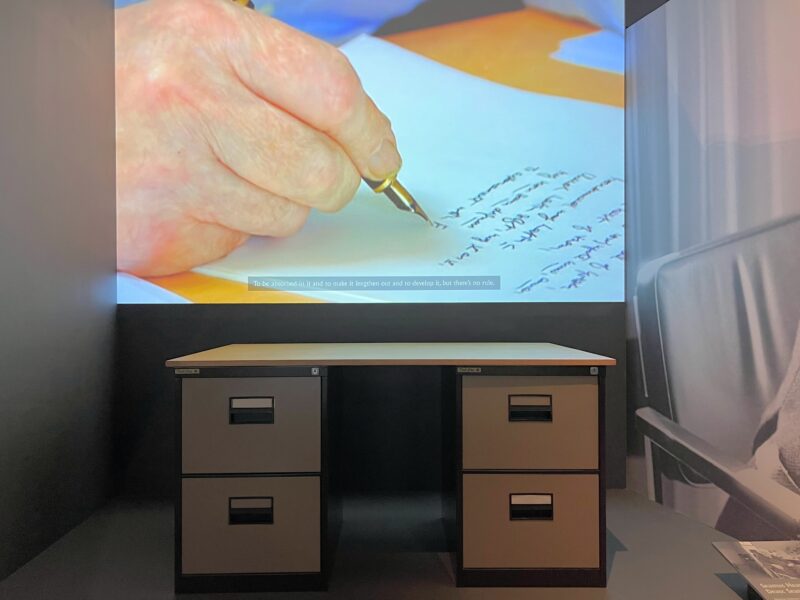

In Dublin we did a few things tourists are supposed to do — the Guinness Storehouse, the Book of Kells — and inadvertently found a few initial clues on the Flaggy Shore treasure map. While doing as Google search for rainy-day Dublin activities, I discovered that the National Library of Ireland had an exhibit dedicated to Heaney. “Seamus Heaney: Listen Now Again” is a deeply thoughtful and moving journey through the poet’s life and work, made possible by Heaney’s desire to share his legacy and his donations of original manuscripts, unpublished works, photographs and other materials — including his desk — to the library in 2011, two years before he died.

I’m so glad we made the time to visit the exhibit, which, the printed guide says, shows aspects of Heaney’s poems that are “about ideas of transformation and the interplay of the ordinary and the extraordinary.” The ordinary became extraordinary for me at the end of the exhibit, where “Postscript” appears in white lettering on a dark gray wall. Ah, there it is, I thought, living up to its name: tacked on as an addendum to a preceding, larger body of work, yet as anything but an inconsequential afterthought.

At some point during the beginning of our stay in Dublin, I noticed a large display of text on the side of a building around the corner from our Airbnb in the Portobello neighborhood. It was so big I hadn’t seen it when we walked right under it in the alley, but it blew my heart wide open while waiting for a bus one day across the street. Three words in gigantic blocks of white capital letters, each word inhabiting its own line as if forming a stanza in a poem, all aligned with the right edge of the three-story structure: DON’T BE AFRAID.

Dublin is full of murals and graffiti. I had no idea what this message meant, and I didn’t see an author tag, but it had a whiff of mortality about it — or perhaps the same spirit of invitation in the opening lines of “Postscript.” Make the time. Take the trip. Do the thing. What are you waiting for?

At the end of the library exhibit, I was caught way, way off guard when I saw the same huge three words projected in white on a dark wall, with an accompanying photo of the mural on the building. The note explains, as Heaney’s son Michael said at his father’s funeral in 2013, that these were Heaney’s last words, sent minutes before he died as a text message to his wife, Marie, in Latin: noli timere. Don’t be afraid.

This surprise hit me like a big, soft buffeting, but I knew I was on the right path toward the Flaggy Shore, led by a seed planted nearly a decade earlier. Maser, the artist who created the mural, said he had read about Heaney’s words and was inspired to share them on a wide scale.

After five nights in Dublin, my husband and I continued our exploration of Ireland, traveling south, west and north, landing in New Quay and in our Flaggy Shore cottage two weeks after arriving in Ireland. Other than having to trade in a dodgy rental car at the Kerry Airport and coping with not just misty rain but sideways, tropical-storm-force buffetings on a few occasions, we had been having a grand time. We were caught off guard especially at sites we hadn’t sketched into our prearranged script, such as the gorgeous and deserted (except for sheep) Healy Pass in the Beara Peninsula, the stunning Kerry Cliffs and a moving, improvisational session of traditional music at Neligan’s pub in Dingle.

The first full day in our corner of Clare dawned blessedly dry and with blue sky, so I ventured out around 8 a.m. while my husband slept. I walked north along a narrow lane to the promised land of the Flaggy Shore, greeted by rocks and seaweed and two brave swimmers. Curious about a marker at a bend in the waterfront road, I approached it to find an homage to Heaney and … the text of the poem.

Jackpot! Heart blown open! Another clue to check off my treasure map. I was getting warmer, almost to the true X of the hunt: the split-screen image in my mind of the ocean and swan-filled lake. Unbeknownst to me, as I learned later, on that first morning out I’d walked past a house called Mount Vernon, which once hosted Heaney’s Nobel compatriots Yeats and Shaw, and other writers. (It’s now a vacation rental.) In talking about the trip that inspired “Postscript,” Heaney notes that he and his traveling companions had stopped to look at it.

On our second morning in our Flaggy Shore cottage, my husband and I drove around New Quay in search of “the ocean on one side … wild with foam and glitter” and the “slate-grey lake,” imagery that evokes a sense of holding the sun in one hand and the moon in the other, joy in equal measure with its companion of peace. Yet another clue on the treasure map had been supplied by my random walk, courtesy of the marker for the poem: Nearby Lough Murree was the lake in the poem. We found it and stopped, greeted by “the earthed lightning of a flock of swans,” albeit at the far shore, others in various states of swanning: “Their feathers roughed and ruffling, white on white, / Their fully grown headstrong-looking heads / Tucked or cresting or busy underwater.”

The buffetings were getting stronger, the doors of my heart blowing open ever wider.

Another clue on the treasure map was checked off later that day when I picked up a framed article on a shelf full of knick knacks in the Airbnb. What did it contain? Why, the poem of course, which was first published in the Irish Times in 1996. I had never before seen this article and its navigational description of the Flaggy Shore.

We revisited the bay-lake area a few more times during our stay in New Quay, in between trips to the Cliffs of Moher, the Burren Perfumery, Hazel Mountain Chocolate and Black Head for a guided walking tour — all fabulous experiences, yet I was still pining to see what the voice in the poem described. As someone who enjoys photography, I know all too well this feeling: “Useless to think you’ll park and capture it / More thoroughly.” Yet I have pulled off countless roads, literally and metaphorically, to try to wrap and preserve a moment in a digital frame. Heaney certainly tried to do the same in words, and I’d say he was more than successful with “Postscript.”

So we tried. We parked next to the sea wall and walked along the paved lane that separates Galway Bay from Lough Murree. Is this where Seamus Heaney stood? (Assuming he got out of his car.) I strained a bit to see the wild glitter in the bay waves and the grayness of the lake, a color that matched the walls in the Dublin library exhibit. It was nearly impossible to capture the image I’d had in my head from the poem, especially without standing on a great height or using a drone (which we didn’t have), but we kept trying, despite the non-photogenic orange traffic cones keeping drivers away from the shoulder of the eroding road.

And it’s okay: I didn’t want to see the Flaggy Shore for its imagery so much as for how the poem made me feel, and still does. It’s often the case that while I’m looking for or at one thing, iPhone or camera in hand, something else unexpected catches me off guard, and it’s often a fleeting thing. Travel can do that, and so can poetry, an art form that ironically uses words to transport listeners and readers to wordless places, interior spaces that can’t be captured.

We were “neither here nor there,” and our presence hardly mattered to the ocean or the lake or swans. But I was happy to be with my husband, Matthew, my partner in life and in travel for the past 30 years, and standing right on the X of the treasure map — and perhaps, dare I say, in Heaney’s footsteps. And was it worth it, traveling 3,500 miles to see less than a mile of rocky coastline? Absolutely. The Flaggy Shore has been immortalized by writers for centuries, and we weren’t through with Heaney’s representation.

On our last night in New Quay, we ate for the third time in five days at Linnane’s Oyster Bar — not just because it was only a few minutes’ drive from our cottage and the only place open within several miles, but because it was delicious and welcoming. Although we had a reservation, no seats were open in the main dining area, so the same server we’d had all week gave us a cozy two-top in the bar, which was fine. Something niggled me to look over my right shoulder, where, hanging on the wall in a matted frame, was a typed version of … “Postscript.” Of course.

Postscript: While in Ireland I saw an ad on Facebook for an evening with David Whyte at a retreat center in Western North Carolina, taking place the week after we were to return to our home near Raleigh. I had been planning to visit my father and sister, who live in that area, at that time anyway, so I signed up. After his talk, Whyte signed books. In the retreat center’s gift shop, I bought one for myself and another for a friend. I was happy to be able to tell him in person a condensed version of this story. I was grateful to be able to thank him for introducing me to “Postscript” and to Ireland, especially the Flaggy Shore.

You don’t have to cross an ocean to have your field of awareness expanded or your heart blown open. Whether your travels take you to another country on an atlas or deep within your own spirit, certain carry-on gear does help:

A commitment to taking the first step, as Whyte has expressed it, possibly into the unknown and possibly with some trepidation.

A researched plan, with space and time for spontaneity and exploring the unexpected.

Flexibility and adaptability.

Curiosity — the willingness to be open and led by dots that get connected along the way, often seemingly without effort.

Maps aren’t made ahead of time, right? They are crafted in retrospect, with firsthand knowledge of the territory.

You can explore your own scenery, and memory, as Heaney did in “Postscript,” bringing a speck of a place in the context of the globe into sharp, gleeful relief. Maybe such a place is just around the corner from where you are right now, or right over your shoulder — in your neighborhood, even your backyard. How many of us made microscopic studies of our environment during the early months of the pandemic?

Part of what the writer and narrator of “Postscript” are exhorting us to do is to stop, look and feel, especially at the unexpected. This often comes with a hubristic, useless attempt to freeze time. But falling short shouldn’t stop us from trying to make more space for joy and peace. Regardless of the results, “Postscript” is saying, by all means, explore. Take in the views. Moments while traveling, however you define it, might catch you off guard, but those experiences often leave the most indelible marks and memories, etched on the heart. You don’t have to go far. Make the time.

You can listen to Seamus Heaney reading “Postscript” here.

Leslie Waugh is a freelance copy editor and teaches writing as a spiritual practice. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, the Smithsonian Magazine blog and various journals, and she has received honorable mentions for essays and poems. She lives in Clayton, N.C., and writes about Joy Magnets on Substack.