by Jessica Monk

if I were as young as you are I would write my thanks & congrats on a larger sheet of paper, but as the case stands, I am obliged to content myself with this tiny miserly scrap which I hope you will manage to read, before you throw it into the blazing fire.

Jane Austen is many things to us: writer, inventor of the modern romance, cultural icon, modern-day vampire. But before her books were used as self-help manuals for traumatized World War 1 soldiers, and before she was the patron saint of fan clubs and Regency horror conventions, she was good dutiful Aunt Jane, the unmarried aunt. She belonged to her family, not the public, and her duty was to them.

If she stole away for a few moments to write down a phrase or work on her novel, this was a mischievous detour from her “work.” And Jane Austen’s “work” meant her needlework.

“She would sit silent awhile, then rub her hands, laugh to herself and run up to her room,” said one of her nieces, strewing a precious glimpse of her life as a moonlighting author.

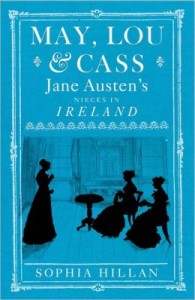

Chatting to Sophia Hillan, author of a recent book that traces Jane Austen’s family connections in Ireland, it’s easy to see why Virginia Woolf insisted that a woman writer needed a room of her own. The sleepy village of Chawton where she lived until her death suggested a settled existence, but for a large part of her life Jane and her sister Cassandra were threatened by the upheavals of births, deaths and marriages, which of course meant the exchange of property. Jane spent 8 relatively unproductive years in Bath after her father gave up the Rectory of Steventon. She even started an unfinished novel there about an impoverished family, abandoning it when her father died and life started to resemble fiction too closely.

Sophia says of Jane’s time in Bath: “She didn’t like that she had no place to work, she had no place to write and she was constantly being besieged by these old 18th century rakes who went to Bath to take the waters and see if they could get married to some nice young girl.”

“She was scathing in her letters about these fellows with their wigs and their powders and their rouge and their patches, she was disgusted by it.”

The only good that could possibly have come of this ordeal were the witty put-downs inspired when the crusty old rakes provoked the sharp end of Jane Austen’s tongue. Flies on the wall got the best of the situation, but the reality for Jane and her sister for an eight-year stretch was a precarious and unstable existence before their brothers deigned to give them a permanent home in Chawton. It’s no wonder that one of her nieces remember that Jane fainted when she heard that the family home was to be sold. The selling of her first pianoforte when the family gave up their house in Steventon was a great loss to her. And though we can never know how deeply this affected her, it’s the small things that tell the story, like her niece Caroline’s recollection of her delight at buying a new piano when she and her sister finally moved into their house at Chawton.

“It is the fashion to be poor, and so of course I am.”

By the time Jane Austen died she had completed enough novels to furnish the Jane Austen box set that we enjoy today. She was always at work on a novel or play – her life divided between family duties and creative work. If she had lived longer, Sophia Hillan thinks she certainly would have written more novels, and that, with Jane around to give her two shillings, Charlotte Bronte would have thought better of criticizing her work.

She never got married, so it might seem strange that marriage would be the master key to her intricate plots. But, for a dependent woman who knew the consequences of marriage and death, who had suffered reversals and improvements of fortunes that were tied to the fortunes of her male relatives, it’s not surprising that her plots eventually contain marriage and put it in its proper place. The beauty of Jane Austen’s fiction is to bring a sense of order and closure to situations that made lives disorderly: there is a beginning, a middle and an end to drama and suffering, and that is marriage.

Sophia Hillan thinks that there’s no better place to look for an example of a life lived with all the “grace under fire” that Jane Austen admired than the life of her niece, “lovely Marianne.” Marianne too fell into the role of ‘the good, sweet uncomplaining’ spinster aunt.

Like Jane, Marianne was an intelligent, industrious woman who was a great letter writer and considered a wit by her family: “She was the originator of many stories and sayings, some of which got into Punch, I believe,” said her relative. She was also the niece who apparently most resembled Jane.

She wore white satin dancing shoes during her first ball season and was considered “bewitching beautiful” by her cousin, who fell in love with her, but as her sisters were married off, she was unceremoniously plucked from the dating circuit of the day to pour her good nature into the common cause of maintaining the family home, only to be rewarded by being made homeless when her brothers chose to sell up.

“It is the fashion to be poor, and so of course I am,” she wrote as an old woman, with her characteristic ironic understatement. Full of self-deprecating humor, she was able to laugh at her age and poverty:

“If I were as young as you are I would write my thanks & congrats on a larger sheet of paper, but as the case stands, I am obliged to content myself with this tiny miserly scrap which I hope you will manage to read, before you throw it into the blazing fire.”

Just as the Dashwoods’ brother did in Sense and Sensibility, her own brother removed her from the family home when he decided to sell up. This was the first in a series of difficult moves that would eventually take her to Ireland. But despite being a victim of her brothers’ whims, Marianne seemed mostly accepting of her lot as accessory to other people’s lives and warmed to her role as the friend and guardian of her young relatives, just as Jane Austen had done with her own siblings.

“It wrings my wizened old heart to think of those times we passed in our beloved paradise,” she wrote to her young nephew, recalling his first steps at the family home.

When Marianne was a very old woman, a family member sent her Aunt Jane’s charade book. In her failing memory, Marianne supplied a one-line biography of Jane Austen that only a family member could give: “I knew she was clever but in what way I did not know.”

The Austen and Knight families had always loved games and theatre, and Jane, among her family, had an exceptional ability for this. In her old age, the single thing that Marianne could recall about Jane was this talent. We could dismiss this memory, but instead why not try to imagine Jane as the adult that young Marianne remembered? Jane was the aunt who took Marianne to the theatre for her twelfth birthday, the aunt who played and sang at the pianoforte and led lively games of charades. In many ways she was the model for the life that Marianne was to lead. As the observer and the victim of family dramas it’s not surprising that an unmarried woman would cultivate an amused and detached attitude to the events that would affect her most. She might even begin jotting down her observations.

If Jane Austen had lived to be an old woman, maybe she would have written letters like Marianne, full of wit and self-deprecation. She might have come up with sayings that got into Punch; she almost certainly would have written more novels. There’s no doubt that Charlotte Bronte would have got the sharp end of her tongue.

and self-deprecation. She might have come up with sayings that got into Punch; she almost certainly would have written more novels. There’s no doubt that Charlotte Bronte would have got the sharp end of her tongue.

Marianne’s Story is Part 2 of a Two Part Feature on Jane Austen’s Irish connection. To read Cass and Lou’s story, turn to Part One.

Fans of Jane Austen and Ireland can join Dr. Sophia Hillan and Richard Mulholland on a tour that traces the Austen family connection in beautiful Donegal. For more information, see our Special Group Tour Itinerary and check out www.specialgrouptours.com.