In small town San Ignacio, the population seems to be permanently on siesta. There’s one cash machine, few shops and only a handful of restaurants. In fact, the most popular restaurants for locals aren’t even ‘real’ restaurants. They’re just shops, attached to locals’ houses, with a few old plastic chairs and tables outside, where they’ll serve you a choice of three types of empañadas and a pizza if you’re lucky.

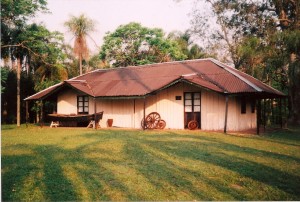

Despite the quietness of the slow paced Argentinian town, tour buses still pull up most days. They arrive to see San Ignacio Mini, one of the best preserved ruins of the splendid seventeenth century Jesuit missions. The town has another tourist site, which isn’t frequented half as much: the house of Uruguayan novelist and poet Horacio Quiroga. A macabre writer of stories, comparable to Edgar Allan Poe in their sheer darkness and suspense, but one I’d never actually heard of.

Seeing as I was spending two nights in the town and had already seen the ruins, I decided I might as well locate Quiroga’s house, which is open to the public as a museum.

I followed the crudely hand painted signs and arrows that led down the dusty roads, pointing the way to his house. The signs seemed to be a joke erected by bored townsfolk. ‘500 metros’ one would say. Eight hundred metres later, another would say ‘500 metros’ again. After another five hundred metres I’d find a sign saying ‘700 metros’. I gave up relying on their information, wondering how long the walk was going to be. Finally, I arrived at a modern looking Argentinian house at the end of a path. Was that it? Was I there at last?

Some locals were lounging in the sun by the porch. “La casa de Horacio Quiroga?” I asked. No. It wasn’t. But it was the right place to purchase a ticket. I did so, stood at their front door, and was pointed to a path that led to the writer’s house.

The narrow trail was walled by tall, all encompassing sugarcane poles. Simply walking through the tall bamboo-like sticks that completely sheltered any view of the house was interesting enough. The walkway wound on like a labyrinth, and every few metres there would be panels detailing the life story of the writer.

And what a tragic world surrounded the life of Quiroga! With each short stroll to the next biographical display board, the reader becomes more and more depressed, and yet the tragedy that struck the novelist’s life was to such an immense degree, that one can’t help but find it a trifle funny, forgetting for a moment that this story is actually true and not one of Quiroga’s inventions.

He was born in Salto, Uruguay, in 1878. Before he was even two and a half months old, his father had died by accidentally firing a gun he was carrying.

When Quiroga was twenty two years old, he found the body of his step father who had committed suicide. Two years after that, his two brothers died of Typhoid fever, and there was still more tragedy to come in that same year. When his friend Frederico Ferrando was challenged to a duel, Quiroga offered to clean and inspect the dueling gun, but accidentally fired it, shooting his friend in the mouth and killing him instantly. After four days in detention, he was released without charge.

In 1908, he bought the plot of land in the dense jungle region of San Ignacio, where he would build his own bungalow. By this time he had already published many short stories, including his famous horror tale The Feather Pillow, and was often compared to his greatest influence, Edgar Allen Poe.

He settled down in the wild backwoods of the Misiones area, marrying Ana Maria Cires and having two children. From a young age, his offspring were immersed in what could be called dangerous situations, supposedly so that they could overcome fears and go through life being able to overcome any obstacle. Once, he left them alone in the jungle one night to fend for themselves. Another time, he made them sit on the edge of a cliff with their legs dangling over the sharp ledge.

During the years in San Ignacio, Quiroga farmed inhospitable land, whilst continuing to write successful stories and poems. The jungle life soon became too much for his wife though, and in 1915 she committed suicide by mercury poisoning.

After some years in Buenos Aires and establishing himself as one of Latin America’s greatest writers, with collections of short stories like Tales of Love, Madness and Death, he returned to his San Ignacio home. He finally settled down there permanently to retire in 1932. He now had a new wife and daughter, but his wife, though youthful, hated living in the wilderness as well, and after a few years, left with their daughter, leaving Quiroga alone.

In 1937, Horacio Quiroga was diagnosed with prostate cancer, which was untreatable at the time. In a hospital in Buenos Aires, he decided he couldn’t take the pain of the disease—and perhaps the pain he had always lived with—any longer. Quiroga committed suicide with the assistance of a friend, by drinking a glass of cyanide.

Walking through the sugarcane sticks that sheltered the house, reading the most tragic tales of his life, it was easy to forget about the popular and critically acclaimed work that he had produced. By the time I emerged from the undergrowth and saw his house for the first time, I felt like I knew the writer I hadn’t heard of only days before.

I walked through the dark tunnels of sugarcane trails, the environment perfectly reflecting the mood, only to walk into an idyllic garden in the hot sunlight, where his small bungalow stood, overlooking the Paraná river.

A reconstruction of a wooden house he had lived in, whilst building the main house, stood to one side. The house, recreated for the 1996 biographical film Historias de Amor, Locura y Muerte, is surrounded by tall palm trees and floss silks with cotton wool coated avocado-type fruits. A single horse minds his own business on the well kept lawn. It’s an absolutely perfect place for a writer to hide away from the world.

Later, I discovered the opening lines to Quiroga’s story, “El Hijo” would reflect the moment perfectly:

“It is a powerful summer’s day in Misiones, with all the sun, heat and calmness that the season can bring. Nature, fully open, feels satisfied with itself.

Like the sun, heat and calm environment, the father also opens his heart to nature.” (My translation.)

The story of “El Hijo” goes on to tell the story of the death of a father’s son, as he routinely walks out into the wild nature of the place carrying a shotgun, and how he’s in denial about what has happened. But I prefer to focus on the opening, which, out of context with the rest of the tale, mirrors what I felt standing there in the garden, where Quiroga may well have arrived at those very words.

The beautiful bungalow was a modest affair. Inside were some original artefacts, as well as replicas of his typewriter and gramophone. Some of his comic strips hung on the wall, showing that he was a talented artist as well. And there were various examples of zoological wonders: stuffed animals, a huge snake skin, and boxes of frames holding butterflies, insects and spiders. Each item reminding the visitor of the incredible natural world beyond the doorstep.

There was thick vegetation all around the surrounding area, but it was still difficult to imagine just how wild the jungle wilderness must have been a century earlier. Quiroga tried to tame the natural world, a theme running through his work, along with love, tragedy, madness and horror.

Though his work is rarely translated into English, Quiroga is regarded as one of the greatest writers of Spanish-speaking world. His life story is fascinating enough, but his body of work even more so. Together they fuel the reader’s interest, as it’s quite apparent where many of his ideas sprung from. Perhaps I wouldn’t have become as impressed by his literature without visiting his home in San Ignacio. Perhaps I’d have seen them as pale imitations of Poe’s.

And while it’s unusual to visit a writer’s house before you read his work, standing in hot sun outside the house Quiroga built with his own hands, knowing the horrors he faced in life, I felt as though I knew it without ever having read a word.

19 comments

Hi Ant, This is soooo interesting!! Must have been amazing being at the house of this man who had such a tragic life. So tragic that your are compelled to laugh in places. I feel sorry for his poor friend!! He certainly had a lot of experience to draw on for his work.

Well done, this is great.

Nita x

Well done antony! Sounds like you had an amazing adventure on your trip and finding out things you knew nothing about before. I had never heard of this Horatio chap but I think the name will stick forever! Love Aunty Trish Iow

Your article is a great depiction of how Quiroga’s house relates to his life and death. His gloomy darkness and mystery is obviously evident in his works, and after seeing his abode, I have a better understanding of his background and how it influenced his literature. Out of the stories I have read by Quiroga, none have happy endings. For example, in his short story, “The Decapitated Chicken”, he narrates, “But Berta had seen the blood-covered floor. She could only utter a hoarse cry, throw her arms above her head, and, leaning against her husband, sink slowly to the floor.”

Original Blog Post: http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/94676/horacio-quiroga

Days after being dumbfounded by the sinister Quiroga story, “El Hijo” I too found myself navigating cautiously through stalks of bamboo and a floor of leaves. The house of Horacio Quiroga’s is nestled on a large plot of land, surrounded on one side by a thick mass of green and on the other, the Paraná river. Like Mapes, I also observed this submergence of the author’s home into nature as a context for his writing. As a thick-skinned, scaly reptile darts out from behind the bungalow and disappears into the jungly brush, a line from Quiroga’s writing, “El Hijo” comes to mind. With imagery that echoes the impressions of his home onto me, “a deep humming sound fills the soul and saturates the surrounding countryside as far as the eye can see.”

(“El Hijo” translation by Margaret Peden)

http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/94699/impressions-at-quirogas-house

After reading El Hijo, the Quiroga house was exactly what I expected it to be. I too found that the first few lines of the story mirrored my experience very well. It was but a hole in the jungle, bordering the Paraná river. I was particularly interested in the way Quiroga raised his children. Roaming the grounds, I imagined his kids wandering the mysterious masses of plant and animal life only to learn how to take care of themselves. Bits of El Hijo flashed across my mind during the entire visit. In this story, a boy, who “has been raised from tender infancy to be cautious in the presence of danger” goes out hunting, and when he does not return, his father decides to venture out to the woods to look for him. When he comes across a fence, he finds his son’s dead body, hanging, with a bullet hole. It shocks me that Quiroga could think of this when he was comfortable enough to send his children into the wild alone. Quiroga’s view of the jungle confuses me, in a sense. It seems as if how unpredictable the wilderness is inspires him.

http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/94767/quiroga-blog-response

When visiting Quiroga’s house over the weekend, I too had felt like I knew who he was and how he reflected his writing through location. Your article was an interesting read, and I agree with your opinion on the mood being affected by the environment of his home. Walking through Quiroga’s bamboo forest, I felt, like the snowball effect, anxiety building up. When writing the short story, “El Hijo”, Horacio Quiroga indicates that exact feeling. He uses personification to give that eerie sense of nature. In the story, Quiroga explains, “…the opening in the esparto grass to tell him that at a wire fence . . . a great disaster . . .”

It is said that Quiroga would make his sons have an overnight stay alone in the forest. This in itself connects to the plot of “El Hijo”. The son is sent out into the forest by himself, while the father stays in their comfortable home.

http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/94801/horacio-quiroga

Hey Antony,

This is excatly where I went last weekend. There have been tragedies around his friends and family. I think being forced to acknolwdge the deaths of his beloved ones overstimulated Quiroga’s mind. Maybe this is why Quiroga often has twisted, dark plots in his story. I feel like he has a off an offbeat moral. This can be seen from merrying his teenage student and his parenting philosophy. By looking at Quiroga’s house I can clearly see the connection and the source of inspirations that he has for writing. The view was beautiful but I can imagine how it feels to be surrounded by bamboos and wild animals in the night time. With a little imagination, it is not hard to come up with a mind twisted plot. In fact the forest is so deep that I can actually feel the spirit of the young boy from the story “El Hijo” running around with a shot gun.

Wanna find out why your post has gone so popular?

Visit me at http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/94675/horacio-quiroga-reply

Thanks for sharing your blog posts with us, THINK Global School!

I agree completely, Horacio Quiroga’s past has obviously influenced his writing and is not another Edgar Allen Poe imitation writer.

Horacio Quiroga’s past seems to have given him an insight to the darkness of the world; therefore, helping him convey the darkness into his short stories. Quiroga shows a solid grip on nature in his stories. His stories make you feel like you cannot change nature, an unforgiving dark nature. After knowing about Quiroga’s life, I understand why he could capture this feeling so well; he had gone through so many situations in which he had seen this darkness. He knew very well one cannot change what has happened. In his short story The Decapitated Chicken, he writes “…hopelessness for the redemption of the four animals born to them finally created that imperious necessity to blame others that is the specific patrimony of inferior hearts.” The word hopelessness says what happened cannot be changed, then following it he writes “created that imperious necessity to blame others that is the specific patrimony of inferior hearts”, thus bringing back the darkness of nature.

http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/94949/horacio-quiroga-insight-to-darkness

http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/94962/respond-to-quiroga-blogpost

Hey Antony,

I visited his house a few days ago and I think it’s very true that you get a kind of depression if you go to his home, especially because it looks like a normal house, a house of an average men, somewhere, but it is surrounded by the dark jungle and if you have some background information about him, it makes the whole feeling even more depressed. Additionally, you can feel and see his depression, when you see the beds of his kids that he sent into the jungle to survive there at night, when you see all the dead insects, which you already mentioned, at the wall, when you see the vibrating and fevering jungle around him. The comic story of the “decapited chicken” that was placed later at the wall of his living room can also give you a kind of depression when you think about his own daughter and wife that left him, because he seems to describe his own realtionship with his wife in his story a little bit as well, “Mazzini [himself] and Berta [his wife] lived for two years with anguish as their constant companion, always expecting another disaster”.

-Paul S.-E.

I had to opportunity to visit Quiroga’s house over the weekend and I can relate to the connections you have made. Like you, I felt that seeing the house and it’s surroundings; where his creations came into existence and how, definitely gave me a better idea of where he was coming from and an insight as to what kind of person he was.

As peaceful as could be, I could see how the mysteries of the jungle that surrounded him provided all the inspiration he needed. I could see how his own life made the jungle what it was for him. In the decapitated chicken, he writes, “Their hopes were not satisfied. And because of this burning desire and exasperation from its lack of fulfillment, the husband and wife grew bitter. Until this time each had taken his own share of responsibility for the misery their children had caused, but hopelessness for the redemption of the four animals born to them finally created that imperious necessity to blame others that is the specific patrimony of inferior hearts.” Living in the jungle, he was surrounded by animals, and in this particular story, their children who he refers to as “animals” surround the parents.

http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/94737/response-to-the-house-and-the-horrors-of-horacio-quiroga

Recently, I too have visited Quiroga’s house in San Ignacio. Before traveling there I read some of his works, such as El Hijo and Decapitated Chicken, and I would definitely agree with you that the stories do a great job expressing the surrounding environment. Walking through the bamboo and jungle on the way to his house allowed me to truly experience how Quiroga must have been feeling when he wrote the short stories; it was as if I was dropped into the setting of that “powerful summer day… with all the sun, and heat,” but I could also feel the anxiety at some parts of the eerie jungle, as did Quiroga when he explained the “cold, terrible, and final realization” experienced when his character thought his son might be dead. All in all, visiting Quiroga’s house was a great way to connect with his writings.

http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/94986/quiroga

After reading your article I felt transported back to Quiroga’s house, the place I visited this weekend. The clear associations you write about the town, Misiones, and the surroundings, gave me awareness about the background of his narrations. Likewise, your article is very connected to ‘El Hijo,’ a short story by Horacio Quiroga about the tragic death of a father’s son. In the narration Quiroga wrote, “Like the sun, the heat, and the calm surroundings, the father, too, opens his heart to nature.” The moment I walked out of Quiroga’s home I stepped onto a perfect lawn and stared pensively; my heart was wide open. There’s no doubt I was spaced out, but my mind was in the place it had to be. I thought about Quiroga, he probably walked on exactly the same soil I did that day, he might as well had stared to the same place I did on that very moment. During my quick, yet reflexive trip I valued the moment and how imperative it is to travel in time when you go to places where other people live. Always recalling their way of life and the heritage they gave to us.

http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/95021/horacio-quiroga

So, here is another comment to contribute to the massive amount of comments from my classmates.

Recently, I visited Quiroga’s house. I completely agree on that Quiroga’s past dictated his stories. You have shown this through his story, El Hijo. This is also shown in his children’s book, Jungle Tales. Even though it was written for children, “The Flamingoes’ Stockings,” still has a violent plot. Seriously, the snakes bite the flamingoes’ legs with their venomous poison—trying to kill them. “But the flamingoes didn’t die. They ran off to throw themselves in the water to relieve the terrible pain.” A dark history is obvious in his writing. His life contained so much death. Throughout his life, he has been coping with an emptiness that cannot be filled. That emptiness is transferred from the pen onto the page into short stories.

http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/95057/comment-to-antony-mapes

A couple of days after I red Quiroga’s tragic story “EL Hijo,” I took a trip to missions and visited the author’s house. Actually, It was exactly what I expected it to be. Two bungalows made from wood in the middle of the jungle, surrounded by a massive amount of green from each side, with a magnificent view on the Parana River. When I got into his house I felt a very weird sensation that still cannot define what it is, just from the way his house is built and decorated I could feel the depression and anxiety that Quiroga talked about in his story. In addition, now that I’ve walked through the long bamboos and I’ve spent sometime in house in the middle of nowhere I can understand why his first wife committee suicide and why his second wife left him. Quiroga had a pretty tough life, he experienced a lot of death and he lived in the middle of the jungle far away from the city and the civilization.

http://spot.thinkglobalschool.com/blog/view/96280/comment-to-antony-mapes