By Suzanne Kamata

The first cannonball shot of the American Civil War may have been fired from Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, but the war had its beginnings in nearby Beaufort. I didn’t realize this until the desk clerk at the Beaufort Inn where I had booked a room for my sister-in-law and me gave us the grand tour.

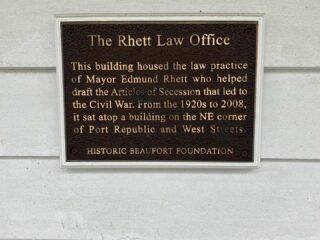

“And this building,” he said, gesturing to the cottage where we would be spending the night, “housed the former law offices of Mayor Edmund Rhett who helped draft the Articles of Secession.”

And here I had thought “The Rhett Cottage” was a reference to Rhett Butler, the hero of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind!

I had a lot of feelings about spending the night in a cottage that had served a defender of slavery. Not knowing its history, I had booked it online because it was the only accommodation available with two beds. However, I let the reservation stand. I was happy to find out later that the cottage had also sheltered wounded Union soldiers, including those of African descent, and, after the War, functioned as a voter registration center for freed slaves.

The pink main building of the Beaufort Inn had once been a stately summer residence. As a hotel, it has hosted the likes of Julia Roberts and Jimmy Buffet. Centrally located, it is an excellent base for sight-seeing. Many restaurants, shops, and a park are all within walking distance. Just down the street stands Nevermore Books, one of two independent bookstores in the city, where I was scheduled to give a talk later that evening.

We stashed our bags and wandered over to Wren Bistro on Carteret Street for lunch. Everyone had told me that I should try the Low country specialty, Frogmore Stew, which is made with corn, potatoes, sausage and locally caught shrimp, but I ordered a chicken salad accented with pecans instead. My sister-in-law who’d driven us all the way from my parent’s house in mid-state, where I was visiting from Japan, treated herself to a glass of champagne.

After lunch, my sister-in-law went back to the Rhett Cottage to do some remote work, while I took a quick look around. I was charmed by the 19th century architecture, and the abundant greenery.

Although small (population 13,607) and quaint, Beaufort has a long and complicated history. Chartered in 1711, it is the second oldest city in South Carolina, after Charleston. And while it may have once been a bastion of white supremacy, it was also the site of the first African American school, and where Harriet Tubman, founder of the Underground Railroad, served as a nurse during the Civil War. A recent award-winning novel, Trouble the Water by Rebecca Dwight Bruff, tells the story of Beaufort-born Robert Smalls, who escaped from slavery by commandeering a Confederate transport ship, and was later elected to the House of Representatives.

The town has also promoted itself as a film location. Several of America’s most beloved movies, including The Big Chill, Forrest Gump, and The Prince of Tides were made here. Beaufort Tours offers golf cart tours of sites from these films, in addition to a tour of spots around town related to author and former resident Pat Conroy.

I had been invited by Jonathan Haupt, the director of the Pat Conroy Literary Center to give a lecture about my new novel, The Baseball Widow, which is set mostly in Japan, but partially in South Carolina. Being a huge fan of the late author who is closely associated with Beaufort and eager for an excuse to visit the city, I had jumped at the chance.

As a newbie Assistant Language Teacher in Tokushima, Japan, I had read The Water is Wide, Conroy’s memoir of teaching under-privileged, mostly Black, students on nearby Daufuskie Island. Now, as an instructor at a Japanese teacher’s college, I sometimes show the subtitled movie version, “Conrack,” to my students. During one memorable scene, Conroy brings his students to Beaufort for trick-or-treating. The courthouse where Conroy filed an objection to his suspension from teaching still stands.

Beaufort was also the setting for his first novel (and the film based on the novel), The Great Santini, which was based on the difficult relationship between himself and his abusive fighter pilot father. His father’s military service is what first brought him to Beaufort. As Haupt would point out during our tour of the Pat Conroy Literary Center the next day, the presence of military personnel, who are often diverse and have traveled far and wide, has made the city more open-minded and cosmopolitan than its size would suggest.

After getting a lay of the land, I returned to Rhett Cottage to prepare for the evening’s event.

Nevermore Books had an eclectic vibe. Round paper lanterns hung from the ceiling. The interior smelled faintly of incense, and the bookshelves were adorned with Japanese dolls. As audience members filed into the store, I was surprised by how many had a connection to Japan. A couple of men had lived there in the past. One woman, Miho Kinnas, now a resident of nearby Hilton Head Island was a haiku poet from Japan, with a family connection to Ehime Prefecutre. We chatted about the results of the summer high school baseball tournament at Koshien and the Matsuyama baseball afficionado and haiku poet Masaoka Shiki. I also had the chance to meet Bren McClain, author of the award-winning novel One Good Mama Bone, who had recently moved to Beaufort. The city, which hosts literary events throughout the year, seems to be teeming with readers and writers. Having been in bigger cities with smaller audiences, I was pleased to receive such a warm welcome.

After the event, still buzzing from adrenaline, my sister-in-law and I went in search of dinner. The restaurant rumored to have the best Frogmore stew was packed, and required reservations, so we ambled over to Panini’s Café on Bay Street, which was adjacent to the waterfront park, for gluten-free pizza.

The next morning, my sister-in-law went running. She later told me that she’d gone over the bridge and checked out some of the historic houses before circling back and going through the military cemetery, where Conroy’s father is buried, across the street from the historic African American cemetery. Meanwhile, I took a stroll down to the boardwalk along the marsh, hoping to catch a glimpse of a dolphin, or maybe some shorebirds. A couple of weeks before, I had read about an alligator attack in Beaufort. I figured if I spotted any large reptiles, I would beat a hasty retreat. All was calm, however.

I met up with my sister-in-law for breakfast at Blackstone’s Café, which served up typical diner fare such as eggs and grits, and was decorated with pennants from various university sports teams. The most interesting feature of the restaurant, however, was its morning ritual. At 8 AM, a bell clanged. The patrons (including my sister-in-law and me) stood facing the American flag and recited the Pledge of Allegiance, something I don’t think I had done since elementary school.

Our final destination on this brief trip was the Pat Conroy Literary Center itself, a small brick building surrounded by palmetto trees and oaks draped with Spanish moss. Although it was closed to the public, Jonathan had offered to give us a private tour. He met us at the door and ushered us inside where we came across a gorgeous screen featuring a scene of the marsh at sunrise. Jonathan informed us that it had been painted by another transplant from Japan, artist Aki Kato. After an informative and interesting tour, I asked for permission to sit at the desk where Pat Conroy penned some of his most famous – and some of my favorite – books.

Alas, there was still so much to see and experience. We departed, vowing to come back again one day. In the meantime, I now had an extended list of books set in Beaufort to read, and I knew that I would be able to visit again any time I wanted to, at least in my head.

Suzanne Kamata is an American living in Japan. Among her most recent books are the novel The Baseball Widow (Wyatt-Mackenzie, 2022) and the travel memoir Squeaky Wheels: Travels with My Daughter by Train, Plane, Metro, Tuk-Tuk and Wheelchair (Wyatt-Mackenzie, 2019). Her essays have appeared in Real Simple, The Japan Times, and many other journals and anthologies.