By Kristy Taylor

When I was twelve, my parents took our family of seven to the small Indian Ocean island of La Réunion to visit my grandparents. While there, my grandparents had to visit a family who lived inside the crater of an extinct volcano. We landed in a helicopter, inside the volcano, and met children who had never seen the ocean despite living on an island smaller than the state of Rhode Island. The year before that, my parents took us all to Morocco where they gave each of us five kids a handful of money to share with the beggars in the bazaar. I still remember the face of the old woman I gave my handful of coins to. My husband has twice taken our two older children to a school in a remote village in Laos where they could volunteer with children eager to learn English.

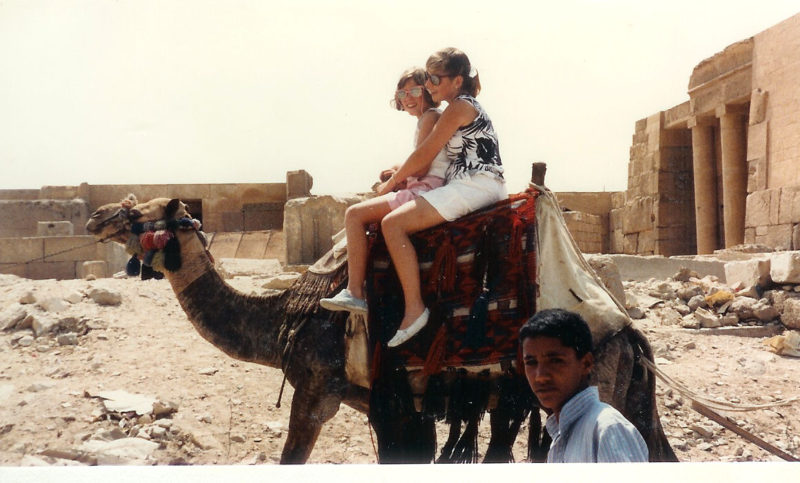

I grew up in an idyllic Boston suburb, my dad was a college professor, and we had two cars in the driveway. But my parents wanted us not to be self-involved teenagers who thought the world revolved around them, and since my dad had summers off, we traveled. It’s impossible to believe the world revolves around you, a suburban American teenager, when you visit isolated Alice Springs, or climb the claustrophobic stairs in the Great Pyramid of Giza. According to Dr. Robin Hancock, an education specialist at Bank Street College, traveling with children helps them learn “the tools for developing meaningful relationships, especially across differences.” As a teenager, I saw the differences between my life and the kids growing up inside the crater of a volcano. My own children listened to the gruesome stories of human sacrifices while visiting Mayan temples in Belize and were bold enough to question the local Mayan descendent who served as our guide about why anyone thought that was a good idea. We saw firsthand what researchers learned in a 2015 study by the Student & Youth Travel Association when they found that 74% of teachers consider travel to have “a very positive impact on students’ personal development.”

Traveling with children can be difficult. On one particular flight to London when I was alone, overnight, with two toddlers, I got off the plane, handed the kids to my parents, and almost turned around to go home. On one of our flights to Spain, my hypoglycemic, teenage brother collapsed and had to be carried off the airplane. However, children who travel see the bigger picture of the world. They learn to adapt, starting with the small things like “they don’t have your kind of chicken nuggets here” and moving on to sitting next to the park ranger carrying the full range of weapons to stop poachers in the Serengeti. They learn empathy for children their same age who, for some spin of the wheel, were born into a much harsher reality than their own.

Traveling doesn’t happen year round though, but reading does and brings many of the same effects. Besides increasing a child’s vocabulary, literacy skills, and overall test scores, reading teaches kids about other people, places, and times. According to Children Educational Services, children who read “learn about people, places and events outside their own experience.” It’s the “outside their own experience” part that is the key. Something in the book needs to connect with the reader—the character, the experience, the lifestyle—that’s how we and our children become engaged; but when the character experiences something different or startling, that’s when we learn empathy. Imagine a character we all know, Jean Valjean, from Les Misérables. Now remember what you’ve always known: “stealing is wrong.” Go back to the first time you read Jean Valjean’s story of all his years in prison for stealing a loaf of bread to feed his sister’s starving family. We can still believe stealing is wrong (as we should), but we can also have empathy for someone put in a terrible position and wonder if we really would have done anything differently. Child psychologist and author of Unselfie: Why Empathetic Kids Succeed in our All-About-Me World, Dr. Michele Borba, explains that children who learn empathy relate better to other people, have better communication skills, and are better listeners. The Children’s Educational Services also tells us “when we read our brains translate the descriptions we read of people, places and things into pictures. When we’re engaged in a story, we’re also imagining how the characters are feeling. We use our own experiences to imagine how we would feel in the same situation.” Our imagination and suspended reality lead us to empathize, which is just what our kids need to learn, too.

Reading also makes history real for our children. The first book I really fell in love with as an early teen, and one that changed my reading landscape forever, was The Count of Monte Cristo. In this novel, Edmond Dantes is falsely imprisoned and spends the rest of his life escaping, then exacting his revenge. It’s set in the shifting sands of Napoleonic loyalties, making young me wonder about the Napoleonic wars and the Emperor’s exile. And when I got to the end of the book and felt outraged by the ending, my imagination fired up and I wanted to write another three closing chapters that I liked better. My children know mythology almost as well as I did after my first class in the Classics department in college because of all the Rick Riordan books they read, and then we can have discussions about which parts are true (inasmuch as mythology is “true”) and which parts are inventions of the author. As an older teenager, when I read Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage, I felt cold during the crew’s freezing months on the ice in Antarctica, hungry as they hunted for seals, and overwhelming relief when Shackleton knocked on the door of the whaling station manager’s house in South Georgia Island. Even if I had traveled to Antarctica myself, I may not have experienced that kind of empathy and understanding. This kind of studying history goes hand-in-hand with traveling—what better place to learn about the London Blitz than in the Churchill War Rooms in London, where Churchill hunkered down to repel the attack. My son recently visited the Chateau d’If, where Edmond Dantes was imprisoned, because he was a fan of the story. Reading and seeing, in tandem, makes the history real and unforgettable.

In both reading and traveling, children get the chance to slow down and unplug. When we take our kids overseas, they only have internet service in the hotel room, leaving about ten hours of the day device-free. Their young, moldable brains get a chance to process the world around them in person and at a slower pace, and the family gets to spend time together without other distractions of a chaotic life. When children are reading, they are focused on the page, on their imaginations as they convert words into pictures in their heads, and on what they are feeling as they read. Common Sense Media reports that teens and pre-teens today spend, on average, at least six hours a day online. Spending too much time in the daily chaos online, makes my children cranky and high-strung, like a top that has been wound too tight. A break with a book settles their young minds and bodies down into a more calm and steady rhythm. They come away from their reading time bringing that temperament with them.

C.S. Lewis told us, “we read to know we are not alone,” and when we travel, we see that we are not the only ones on this planet. In a world where it seems like he who yells loudest wins, the things reading and traveling teach our children–slowing down, empathy, a broader worldview—can help them not just learn to relate to the world around them, but to thrive. They can adapt to differences in opinion and situation; they can approach other people with compassion and understanding; they can take the time to slow down and remember what they learned and how they felt with their last book or last trip. They can learn that they don’t need to compete to be the loudest.

Kristy Taylor studied French, English, and Humanities as an undergraduate and has a Master of Arts in Italian Renaissance Humanities from Brigham Young University. She has been an English teacher, copy editor, and technical writer. Currently she serves on a Board of Directors for a non-profit tasked with preserving and digitizing historical documents. She writes the Life of a Queen series for Anglotopia, and you can always find her at the book and travel website, www.aworldelsewhere.net.