I arrive in Havana, Cuba, at the end of 2010 together with a guide book and several men: Our Man in Havana, The Old Man and the Sea, and Paul, my partner. I wonder whose footsteps I’ll follow in, but after a single night in Havana it becomes clear that Hemingway’s footsteps have been well and truly trampled. Hemingway = Cuba = CUC (the Cuban peso). CUC is tied to the dollar and necessary for purchasing anything other than marketplace peppers and potatoes. Hemingway, it turns out, is big business. Every bar and restaurant Hemingway frequented (or simply stepped foot in) cashes in on the Hemingway legend. As Hemingway lived in Cuba and went to many bars, I add up that I couldn’t afford to follow in his footsteps. Graham Greene, author of Our Man in Havana isn’t quite as popular in Cuba, and therefore more (financially) attractive. Greene’s novel was also written in 1958, the year before the Cuban Revolution. I’m intrigued to discover how much the Havana and, indeed, Cuba has changed since then.

I learn pre-revolutionary Cuba was a rich man’s playground, in which anything is possible and for whom decadence is prevalent. With a booming sugar industry, United States companies own two-thirds of Cuba’s farmland by the 1920s. Al Capone and the American-Italian mafia have moved into the Hotel Sevilla-Biltmore and set up a tourist industry based on booze, sex and gambling. On the other side things, there is extreme poverty. Since declaring its republic in 1902, Cuba has suffered from serial corrupt leaderships. Fulgencio Batista, whose dictatorship was overthrown by the Revolution, enacted a military coup in 1952 that suspended a citizen’s right to strike.

During these years, Fidel Castro and his brother Raul Castro decide they need to mobilize the Cuban people. Fidel is imprisoned for tactics, but revolutionaries are being born by the minute. Upon the arrival of Argentinean Marxist leader Che Guevara, it is only a matter of time before the Revolution. The way Green describes it, 1958 Cuba is a dizzying cocktail of rum, gambling, prostitution, American mafia, a ruthless military dictator and cigar-smoking revolutionaries, mixed with an international backdrop of the Cold War.

When Wormold, the English protagonist of Our Man in Havana, is recruited by Ml6 agent Hawthorne to spy on the Cuban government for the British under the guise of a vacuum cleaner salesman, Hawthorne says, “We must have our man in Havana, you know. Submarines need fuel. Dictators drift together.”

At a glance, apart from the absence of U.S. mafia, expats and MI6, the Cuba of Green’s account of Cuba in 1958 and my account of Cuba in 2010 are not entirely dissimilar. The same American vintage Chevrolets, Cadillacs and Buicks grumble through the streets, coughing out blue plumes of carbon monoxide. Hundreds of tourists swarm around the city drinking Daiquiris and smoking Cohibas, while hundreds more Cubans swarm around the tourists offering various services from cigars to taxi rides in horse-drawn carriages. Not unlike the opening of the novel a man limps by us as we cross Prado and a woman dressed in a patchwork skirt begs for clothes. ‘No es facil’ (It’s not easy) becomes one of the first phrases we learn, and one that closely represents many people’s lives in Cuba. I get the impression that the poignant words of Wormold’s friend Dr Hasselbacher, still echo through the country today:

‘You should dream more… Reality in our century is not something to be faced.’

Paul and I search for the evocative settings of the novel. For example, we find the Hotel Sevilla (where Wormold meets with both Dr Hasselbacher and Hawthorne), the Hotel Inglaterra (where secretary Beatrice stays) and the Nacional (where a dog is poisoned instead of Wormold) still exist. They are just as resplendent as they were in the novel – their huge lobbies and bars where guests hover, talking and smoking, evoke a bygone era. The Wonder Bar (where Wormold takes his morning Daiquiri with Dr Hasselbacher) and Sloppy Joe’s (where Wormold’s recruited into the Secret Service in the toilets) no longer exist, and the Shanghia and seedy Esperanto strip clubs were closed down, but the famous Tropicana, where Wormold, his daughter Milly and Dr Hasselbacher go on Milly’s 17th birthday, is still thriving – on a staggering 80 CUC entrance fee. Hemingway seems like the cheaper literary tour after all, but as I read about it aloud, the desire to see it grows:

It was a more innocent establishment than the Nacional in spite of the roulette-rooms, through which visitors passed before they reached the cabaret. Stage and dance-floor were open to the sky. Chorus-girls paraded 20 feet up among the great palm-trees, while pink and mauve searchlights swept the floor.

“Can’t we go?” Paul asks counting out his CUC.

He’s consoled by a Daiquiri at El Floridita. El Floridita is known as a Hemingway hangout (clear by the live-size statue of him perpetually slouched at a corner of the bar), but it’s also where Wormold met his wife and her family. The Havana Club rum bottle sprints over the glasses as the barmen make Daiquirís and Mojitos en masse. The place is loud, full of mainly well-off tourists smoking cigars or cigarettes and sucking at straws from dainty cocktail glasses. Two brash, beautiful Cuban women, dressed in red and black costumes, rumba and salsa whille an elderly man in a cap plucks at a bass. I imagine little has changed in over 50 years – except that Hemingway is no longer real and a Daiquiri cost 7 CUC.

Drinking and smoking seem to be a constant thread in Havana history. All the Green’s characters drink vast quantities of rum and whisky and smoke cigars and cigarettes – of course in those days it was considered glamorous. Even Milly smokes cheroots and Beatrice is offered a Marijuana cigarette in the Shanghai. To this day, despite anti-smoking sentiment by some westerners, a thick haze of Cuban tobacco drifts through the intoxicating streets.

And despite Fidel Castro’s best efforts, prostitution refuses to disappear. Wormold believes “…the sexual exchange was not only the chief commerce of the city, but the whole raison d’etre of a man’s life. One sold sex or one bought it – immaterial which, but it was never given away.” It seems like every stunning Cuban woman cruises around with an older western man, and handsome Cuban men escort older western women – and everyone drinks another Mojito or Cuba Libre, lights a cigarette and smiles contentedly.

Outside El Floridita, the streets of Havana pulse with life. At every corner, like in the novel, people call out ‘Taxi?’ A red stretched Lada and a Cadillac pass us when we get into a bici-taxi. As we thump along the streets for 3 CUC, I wish we opted for the Lada as the cyclist tries to avoid the potholes. The old Spanish, Moorish and French buildings bounce by us, with their jaded beauty, pockmarked and hungover, semi-veiled by the dark.

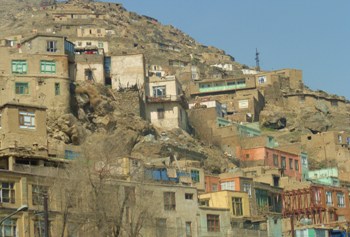

Just beyond the main squares the streets are even darker. Cuba suffers from severe energy shortages. In a bid to declare Cuba the most ecological country in the world, Fidel Castro switched the country over to energy efficient lighting; despite the four-litre gas guzzlers, Cuba probably (out of necessity) ranks among the top contenders. Beyond the central squares and main streets, much of the country remains in darkness, or glows like a ghost.

Even darkness is a similarities between Green’s Cuba and this one. Wormold writes to his sister that vacuum cleaners aren’t selling considering the “electric current is too uncertain in these troubled days.” And when he’s in Santiago, Wormold says “‘… the night was hot and humid, and the greenery hung dark and heavy in the pallid light of half-strength lamps.”

Neither light nor scenery appears to have changed. As we sit on the sea wall along the elegant curve of Malecon, Avenida de Maceo, under the blue sky, the sea pounding on one side and the pink and grey crumbling pillars of abandoned buildings on the other, I’m reminded of Wormold describing the walk back from the Consulate.

The long city lay spread along the open Atlantic; waves broke over the Avenida de Maceo and misted the windscreens of cars. The pink, grey, yellow pillars of what had once been the aristocratic quarter were eroded like rocks; an ancient coat or arms, smudged and featureless, was set over the doorway of a shabby hotel, and the shutters of a night-club were varnished in bright crude colours to protect them from the wet and salt of the sea. In the west the steel skyscrapers of the new town rose higher than lighthouses into the clear February sky.

Of course there are differences between Cuba then and Cuba now. Green describes Obispo, one of the central drags of Havana, as busy; it takes Wormold half an hour to get through the traffic. Now it would take two minutes. When Wormold goes to Santiago to visit his retailers, his car breaks down and he catches a bus to the southern dissident city. Catching a spot on a bus would be quite unlikely today, as every vehicle is bursting at its seams passengers. Hundreds of people wait by every junction on every road to get from A to B.

On our drive to Santiago we stop to ask directions and acquire two fishermen for the ride. When we break down with a flat tyre they suggest one of their cousin’s repair it. We are subsequently charged a Hemingway-high price of 40 CUC.

‘No es facil,’ we’re told.

But fortunately, which things truly aren’t easy there, Cuba isn’t violent. There are no gunshots in the city, no stabbings, no tourists or locals are robbed and killed, the police don’t assault the people. It seems as though Cuban’s have no suspicion or fear. Today, it’s the sounds of Buena Vista Social Club and harmless touts, rather than the bleating voices of revolutionaries and whispers of spies that fill the bars, squares, restaurants and streets. The once blazing Communist slogans, Revolucion es Liberdad! Igualdad! Justicia!, are fading like a flag in the sun.

One Man in Havana remarks on the fear the Western world has of Communism, because it does away with class distinctions. Chief of Police Captain Segura, who carries a cigarette case made of human skin, tells Wormold about the existence of a ‘torturable’ class and a ‘non-torturable’ class – Segura’s father we learn, was tortured to death by a police officer. It was that same police officer whose skin provides the case for Segura’s cigarettes. Communism it suggests, gave the people equality at least.

Back in El Floridita we perch at the bar next to Hemingway’s statue, and order a final Mojito.

Cuba is still a dizzying cocktail. Rum, prostitution, a somewhat benign dictator, touts and cigar-smoking tourists, set against an international backdrop of globalisation. Many things the Revolution strived remove from society have come back like virus; and there is a new divide between the CUC haves and have-nots. But contemporary things are not far off. Cars, washing machines and property development are becoming visible after over 50 years at bay. Cubans and foreigners talk and dream about what Cuba could be.

‘Things will change soon,’ I say to Paul. ‘Cuba will change.’

Paul, puffing on a Montecristo, nods, and begins talking to a man next to him in a ‘Yankees’ baseball cap about Chevrolets.

‘What do you think of Cuba today?’ I ask Hemingway, still sitting next to me at the bar.