By Katherine Gypson

“This is a great moment, when you see, however distant, the goal of your wandering. The thing which has been living in your imagination suddenly becomes part of the tangible world. It matters not how many ranges, rivers or parching dusty ways may lie between you; it is yours now for ever.” – Freya Stark

The sad eyes of Ahmad Shah Massoud pull me out of the armored car and into the traffic circle, into the mess of a Kabul street at night – cars without headlights, cars seemingly without drivers, cars making their own lanes as they swing around and off into the broken maze of the city.

Headscarf unraveling, I can barely see where I’m setting my feet. I’ve seen yawning gaps in concrete and sewage-filled holes that could shatter an ankle. All I know is that I must get a photo of the famous Afghan mujihadeein’s portrait presiding over the circle, his face flattened by glowing swathes of multi-colored lights.

As a girl, I treasured tokens of other places – old coins bearing the faces of dead kings and powder-blue pages from pen pals in twelve different countries. I read travel books as if they were maps for a future life. The first mark in my passport – a visa to Afghanistan – felt as solid an accomplishment as any diploma.

Now, it’s the eve of Nowruz, the ancient Persian festival of spring, and I’m standing in Kabul on my own, taking pictures of a dead warrior covered in Christmas tree lights. My Afghan bodyguard catches up, wearing the pained expression of a father watching after a child. He said pictures were okay but now he looks worried.

I’ve been locked up, breathing the same stale air for four days, always covered, going from one secure room to another. I’ve been good until now, obeyed all the rules but I don’t want to leave without walking on my own for a few minutes, to know all I can about this place that’s lived in my imagination. What does the night sound like as the city settles into sleep? Will the breeze from the mountains feel warm with the coming spring?

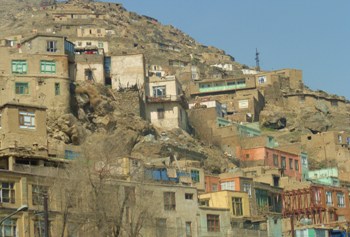

In daylight, rows of shacks stagger down the mountainsides, clinging to a life unrelieved by the basic comforts of color, warmth and space. The night erases that uncertainty, floats the lights in an endless darkness above the city. I’ll never know the lives inside those houses. I’m here in Kabul but I’m still not close enough.

*

Forty years earlier, legendary traveler Freya Stark visited Kabul and found “an untidy sprawling city [that] struggled for form among the hills.”

To see the places she dreamed about, Freya overcame poverty, a gruesome childhood face injury and her generation’s low expectations for women with an ear for languages and an insatiable curiosity. For seventy years, she mapped the secret places of the Muslim world, writing beloved books in lush, literate prose and earning herself a title – Dame of the British Empire .

When I read Freya’s work, I see landscape, people and history as essential but not the deepest and most profound elements of travel. The place in Freya’s imagination, the pulse she senses underneath all, is just as important. I treasure her books for this reason.

In a life full of adventures, Freya’s jaunt to Afghanistan to see the minarets of Djam was almost a footnote. What would have been an extraordinary life-changing adventure for anyone else became a short book for Freya. In her time, Kabul was the civilized rest stop before the wild world out beyond. She moved on to more secluded parts of Afghanistan , climbing to a secret valley surrounding an ancient minaret, the lone survivor of a once flourishing civilization.

The Kabul I know is framed by car windows and life on the streets takes place in the lulls between my car getting stuck and then speeding up. When Freya wrote that Kabul “thoroughfares are building with an eye to the future” she saw a city in love with the Beatles, bustling with hippie tourists and looking to reclaim its marker as a crossroads of trade. As I stare out the window of my armored car, I see what became of that future.

From the corners of fruit stands, posters of President Karzai’s jovial false smile compete with Massoud’s sad eyes gazing out at packs of wild dogs and sheep roaming in search of piles of trash. Big-bellied policeman balance on stands painted in circus colors, vague gestures the only clue they might be attempting to direct traffic. A full bouquet of balloons in yellow, hot pink and deep blue float past the faded sign for the Kabul Zoo – an old man clutches their strings as if he’s carrying the weight of the world.

I promised myself I would look beyond the filth and the poverty, the weight of thirty years of destruction. I want to see the pulse of the place the way Freya had on a spring day in the 1960s when she observed, “One is apt to forget Kabul’s snow while dusts blows among the pyramids of melons in her streets.”

I look for color in spite of the dust; mint-green concrete compound walls and toys bunched in shop windows, made out of the aggressive colors that can only exist in cheap plastic. Billboards a head higher than the life going on in the street advertise “your dream job” and “superior cell phone service”

The vibrant colors and absurd contrasts give the feeling of a dream constantly unraveling before my eyes; an effect heightened by the barriers that keep me from exploring. Even if I could escape my bodyguards, I’m not sure I would know what to do in these streets. Do I walk differently than an Afghan woman? Have I wrapped my headscarf in the local way?

Somehow, I think Freya wouldn’t have worried about such things. She famously brushed aside such formalities as passport controls, visa applications and escorts, preferring to go her own way at her own times. I imagine her giving the driver the slip and striding off into the streets.

I watch the men crouched on the roadsides and wonder at their use of space. What must it feel like to cram and arrange all your life into carts and shacks, to have your entire livelihood depend upon a space the size of a closet?

Sun catches on the iridescent scales of fish, their flesh exposed and raw. Hundreds of luscious strawberries balance in a pyramid on a wooden board. Women lift the hems of their burqas and move among the carts, revealing pencil-thin heels in black and red. Perhaps I wouldn’t fit on the streets of Kabul after all – my square-heeled boots a sign of a world that makes too much sense.

Beyond, the snow-covered mountains float around the edges of the city, impossible wallpaper for daily life.

*

A man stops us as we walk to the market. I hear him before I see him. He makes a moaning sound calculated to make us stop. His face is modeled around bones and pain and he keeps rolling, rolling faster in his cart to get to me. It’s then that I see how he moves – his wiry arms digging into the ground, pushing a red cart along in the dust and rocks. The rest of his limp body curls up, ending unnaturally at the hips. He has no legs.

I tell myself, you’ve read about these things. You knew the landmine victims and the beggars would be part of Afghanistan . This is part of what you need to see to understand this place. I swallow a gasp and know that he horrifies me. His body is a broken version of a human being. I think about the dollar bills in my purse and I tell myself I’ll stop and hand him one. But my group huddles closer and moves on. I move with them. Up ahead, I see a burqa-clad woman clutching a baby. She’s already walking towards us, hand outstretched.

Once, in another lifetime of Kabul, Freya Stark watched an American Embassy performance of Twelfth Night. “It is remarkable,” she noted, “how naturally Shakespeare fits the East…in India, or Kabul or Istanbul… there is no necessity to labor an atmosphere; it is already in the air we breathe, in the cruelty, poverty, gaiety and philosophy of the bazaar, in the Unexpected ready to happen around every corner.”

As I’m led away from the beggars, I think of that long-ago play held in the last years of Afghanistan’s peace. I hate Freya’s casual reference to cruelty. She places it at the center of her pageant of Middle Eastern life, like an actor in a medieval morality play representing vices and virtues. But that’s the danger of coming to a place that’s lived in your imagination for so long – you see the things you want to see. Within moments, I’ve shaken off the encounter and I’m looking for something to buy.

The market reminds me of tent cities I constructed as a child – tunnels of brightly-colored fabrics leading maze-like to more things to buy. Like everything in Kabul , the goods spread out for purchase are just a bit odd. Jeweled birds perch on rings. Indian dancing girls shuffle in lines across a silk scarf. I lift up a horned helmet welded out of heavy coins. It could be as old as the invasion of Genghis Khan or it could be an ambitious fake made yesterday – set in a shattered concrete landscape saturated with the smell of diesel fuel, it’s difficult to label anything new.

I buy a lapis cat carved with a coy smile because it reminds me of the matted stray guarding the gates of the US Embassy. Flexing her claws in and out, she slides along the ankles of the young Afghan guard slumped in a chair. The camouflage uniform and AK-47 do little to disguise the guard’s youth. He’s perhaps sixteen or seventeen years old. Each visit, I play with the cat while he embarks on a complicated performance of checking ID’s and confirming appointments.

On my last day in Kabul, the cat is missing. The guard and I eye each other. He’s already showed off his cell phone and asked the purpose of my visit at least four times. Off to the side, I see a plastic dish of dry cat food.

I point and ask, “Does she have a name?”

He smiles, “No name. Just cat. She’s always here.”

I think about the boy, seeking out and finding cat food in a city where sheep eat trash and legless men in carts beg for a coin. I wonder how much he’s paid to sit here and watch the traffic circle endlessly around Massoud. I wonder if the money he spends on her food is worth having a small companion for his days.

“The cat is gone,” he says. “She’s gone and I don’t where she’s off to.”

*

I leave Afghanistan only six days after arriving. Almost everyone climbing the stairs to the plane take forbidden photos of the mountains circling the airport. I study the mountains, trying to save it all up in my mind.

I always feared that seeing the things I’d built in my imagination would ruin them, somehow take them to a place that was no longer mine – a place that no longer belonged to me but was held fast in the real world.

I know I’ll go home and I’ll tell people, “I saw it. I saw Afghanistan .” My stories will make me part of a company of travelers and in some small way a companion to Freya’s journey. But I’ll know that’s false. I’ll be talking about the things I saw outside car windows and I’ll have to live with the possibility of never returning to discover more.

As we gather speed down the runway and swing up into the sky, the mud-colored houses and dirty air blending into a haze of colorless clouds, I think of Freya. I expect she would have smiled at my formless anxiety and told me to wait, to make other chances down the road.

Kabul is now part of my imagination and my real, tangible world. As I leave Afghanistan, I repeat the prayer of all travelers. I pray for the chance to return and see where the two meet.

*

Slideshow cover photo by Ricymar Photography

Originally Published in 2012

3 comments

Beautiful story where writer moves back and forth Freya’s world and her own reality and imagination.

She kept the story moving, seeming to literally move with interest as well as movement itself

among the things and people she saw, each new scene complimenting, not intruding, on the scenes just visited. Her thoughts on what she saw and on Freya were not ‘reports;’ they worked in well with what she saw and the experience she wrote of.

I take it the little dot between some paragraphs were where she had to cut for the number of words allowed. It’d be interesting, if they were more scenes, to know what they were.

Thank you for your lovely comments. The trip to Afghanistan was the experience of a lifetime and it meant a great deal to me to be able to write about it.

David – to answer your question – the dots are to delineate section breaks and show where a new portion/grouping of thoughts in the story begins.

I have many more stories from Afghanistan and am always working to shape them into new essays!