By Mark D. Walker

My wife and I first met Salvador and Erika, two jewelry artists from Chihuahua, Mexico, in their booth at the 2019 Sedona Art Festival. We were admiring their stunning array of silver and copper jewelry when Salvador showed us a photo of an ancient Mata Ortiz pottery bowl. It was from a Pre-Colombian culture in Chihuahua, the Paquime, whose designs had inspired much of their work.

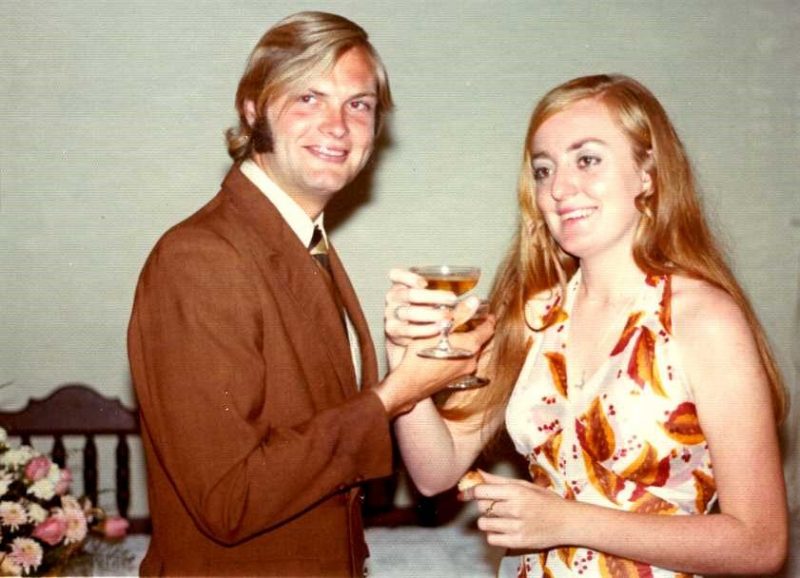

“My wife, Ligia, and I have traveled back and forth through Mexico from Guatemala a number of times over the years, including our honeymoon,” I said. “Here’s a few photos of our honeymoon trip from my book, Different Latitudes. “We got as far north as the state of San Luis Potosi when we started getting Tex-Mex music 24-7.”

I then showed them a picture of a book I was reading and reviewing, Paul Theroux’s On the Plain of Snakes: A Mexican Journey. “He traveled back and forth over the border to get as many stories as possible from people who were at an asylum center trying to cross the border into the United States. On one of these trips, he saw a middle-aged woman praying before her meal in a migrant shelter. Maria was Zapotec, from a mountain village in Oaxaca, and had left her three young children with her mother while looking for work north of the border. This image of her praying reminded the author how resilient migrants are and inspired him to carry on his journey south until he reached Oaxaca and Chiapas in the South. I think you’ll find it a good read.”

While Salvador and I were chatting, my wife was getting to know Erika and checking out the jewelry. Before long, she purchased a bracelet. It was made of native silver and copper with a distinct design, which I quite liked.

As we were leaving their booth, Salvador and Erika shook our hands and said, “Thank you for speaking to us in our language and appreciating our culture and art so much!” With that, Salvador revealed that although they had participated in several art festivals in Tucson over the years, on this trip, for the first time, four separate cars had lowered their windows to flip them the “bird” when noticing their Mexican license plates. “We were really taken aback by their apparent hostility and aggressiveness!” explained Salvador.

“I was actually afraid they might get out of their cars to hurt us,” added Erika.

With that, Salvador and I looked at one another in a moment of contemplation. I wondered what motivated those fellow U.S. citizens to show such disrespect and outright hatred to visitors from our neighbors to the south. At which point, I realized the impact of those now infamous words, “They send us their poor, their drugs, their rapists…” As we were leaving the Art Festival, I reflected on Salvador’s comment and the shame I felt about the hate talk incident in Tucson despite the many things our countries have in common.

You don’t have to kick around Arizona and New Mexico for long to appreciate our common heritage, including the fact that until the mid-1800s both states were part of Mexico. The food, wildlife, music, and history have many parallels. Both sides of the border even share similar business segments, including copper mining and cattle ranching enterprises.

On both sides, you can still find 1,000-year-old petroglyphs that include human stick figures, pregnant animals, and geometric designs of uncertain meaning from past cultures such as the Pima Indians—descendants of the Hohokam—whose descendants interacted with the Spaniards, and their mission churches like San Xavier del Bac south of Tucson, which has a history going back 200 years and is part of a chain of mission churches stretching from northern Mexico to northern California.

My decision forty years ago to pass on a luxurious resort in Guatemala and take my new bride on our honeymoon getting to know some of the history, culture and cuisine of Mexico was the right one, and would begin an ongoing love for Mexico and its people. We headed over the Cuchumatanes Mountains into Mexico, stopping first in the colonial town of San Cristobal de las Casas, which is filled with art and pottery of every color, reflecting both Mayan Indian and Spanish Colonial influences. Our 2,500-mile trek would take several weeks, northeast up the Gulf Coast and then back down the Pacific side on our return home.

The next day and many miles later, after passing through Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico, we found ourselves swallowed up in the mega-metropolis that is Mexico City. We headed directly to one of the most spectacular museums in the world, the National Museum of Anthropology, by far the largest in the country, with significant archaeological and anthropological artifacts from Mexico’s pre-Columbian heritage, like the Stone of the Sun (the Aztec calendar stone) and the Aztec Xochipilli statue.

Six years later, we’d return to Mexico. This time with two children and a mandate to raise funds in California for my work in Guatemala where I had helped set up a small, rural development group. On the way to California, we passed through Mexico City at the time of Pope John Paul II’s visit in 1979. We were hosted by a group of Charismatic Christians for the celebration, and our group of twenty pilgrims stood on the road and cheered as the Pope drove by in his Popemobile—we felt the energy and enthusiasm all around us from Mexicans of all ages.

We learned that we would be staying with the Jimenez family in the community of San Jeronimo. The head of the family, Ramon, owned a successful copper chimney company. Their home was perched on the side of a hill with an amazing view of the metropolis below.

In San Jeronimo, our two-year-old, Nicolle, contracted “thrush,” which covered her throat with a cotton candy-like substance. It was so painful she couldn’t swallow. Since we had little money and no medical insurance, this caused us much angst. But Ramon’s wife, Luisa, pulled out a box of household medications and said, “No tengan pena (don’t worry) Marcos y Ligia, we use homeopathic remedies which strengthen the body’s ability to ward off such ailments, and I have just the thing for Nicolle.” With that, she mixed some powders together in water and we convinced Nicolle to swallow it. Within two days, Nicolle was enjoying red beans, rice, enchiladas and other local delicacies with the rest of us, and we were able to head on to California. The Jimenez family had been a real godsend for us in working through Nicolle’s illness, and we hated leaving.

Over the years, I have returned to Mexico as a fundraising consultant for several charities—Mexico has over 4,200 philanthropic groups. As a member of the Association of Fundraising Professionals, (AFP), from 2005-2008 I led workshops for some of the 350 fundraisers from all over Latin America at the annual Hemispheric Congress for Fundraising in Mexico City.

In 2008, I spoke at the first Day of Philanthropy event in Guadalajara and was invited back again in 2011. My gracious host, Marcela Batiz, the President of the AFP West Mexico Chapter, took me on a tour of the historic center of the city with several members from her AFP chapter. We went into the Hospicio Cabañas to view “Man of Fire,” my favorite Mexican muralist’s illusion piece. Jose Clemente Orozco revolutionized the fresco technique and educated the public at the same time.

The event itself was hosted by the local chapter of AFP in the Paraninfo at the University of Guadalajara. The focus of my talk was on cross-border fundraising opportunities and, as I stood on the stage in front of over a hundred and fifty local fundraisers, I momentarily forgot that I was the speaker, as I was transfixed by the spectacular frescoes of Jose Clemente Orozco, which covered the entire ceiling of the auditorium. Finally, I noticed that the audience was staring at me and I realized they were waiting for me to speak. Fortunately, I came down from the heights of Orozco’s inspiring murals and began my presentation on how to raise funds from major gift donors as well as on some nuances of cross-border philanthropy.

That evening, Marcela and the AFP board members presented me with the traditional participation plaque, as well as the Guia del Tequila (Guide to Tequila) recipe book. The book provides the history of the best-known product from the agave plant and some of the best dishes in which tequila is an ingredient. My favorite main dish included in the book is “Levanta Muertos” (Raise the Dead), handy after consuming an inordinate quantity of this Mexican elixir, which the locals insist tastes like a “burning river.”

Several years ago, Ligia and I met Mexican sculptor, Jess Davila, and his wife, Coyito, at the Arizona Fine Art Expo in Scottsdale. I was taken by his creative, expressive sculptures made out of marble, alabaster, sandstone, and limestone.

I discovered that Jess had founded an Arts and Cultural Center in Huachinera, Mexico, his hometown in the state of Sonora. The Center had erected six buildings, which Jess and other fellow artists use to help locals find their artistic talents and learn how to make a living at it, as well. When Jess learned that I was a professional fundraiser who worked for numerous international charities, he recruited me to work with the board of Heart, an organization he formed to promote and raise funds for the Center. He invited my wife and me to attend their annual Festival of Art, which is co-sponsored by the Sonoran state government and is Heart’s major annual fundraising event.

So, in October of 2008, we crossed the border at Douglas, Arizona, and headed south through Moctezuma and up to Huachinera, located at the base of the Sierra de Madre mountains. The town only had one small hotel at the time, but Coyito’s family was close by and provided us meals on more than one occasion, making us feel at home in a new community.

After the first day’s activities, we walked down to an open-air amphitheater to listen to several local traditional musical groups, including several from the Yaqui indigenous community. As the evening unfolded, we sat back to enjoy the native sounds under a dome of stars above. The next day we attended a concert in town, which ranged from a 10-year-old’s rendition of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” to a concert quartet and various folkloric dancing groups. The students’ artistic work was displayed throughout the rooms of the cultural complex, and the level of creativity and inspiration that went into it was impressive.

We still look for Jess and Coyito each year at the Arizona Art Festival and now bring some of our grandchildren so they can ask Jess what inspired him to sculpt a given statue or ask, “What kind of rock is that?” He even has a small workshop in the rear of the exhibit where the kids can see him in action.

Over the last 45+ years, Ligia and I have felt fortunate to live close to our neighbors to the south and to cross the border to enjoy the art and culture there, which reflect centuries-old Indigenous, and Spanish colonial, influences also found in the Southwest of our own country. While there, we also see old friends and make new ones who introduce us to cultural nuances and hidden mysteries to be found in the most unlikely of places, bringing our bracelet full circle. Although we couldn’t right the wrong of the hate shown to our new-found friends from Chihuahua, Ligia will always wear her new bracelet in style and with pride and we will continue to look for the next opportunity to head south of the border. Maybe another 2,500-mile road trip up and back from Guatemala? Then again, maybe not.

Mark D. Walker is is a contributing writer at Literary Traveler. He was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala and worked with international agencies like MAP International, Hagar and Make A Wish International for over forty years.His memoir, Different Latintudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond was recognized by the Arizona Literary Association and one of his 25 articles was recognized by the Solas Literary Awards for Best Travel Writing. His wife and three children were born in Guatemala. Over 60 book reviews and 25 articles can be found on his website, www.MillionMileWalker.com and you can follow him on facebook at https://www.facebook.com/millionmilewalker/