By Julie Dalrymple

The weather report for England showed two weeks of continuous rain – fitting weather for a literary pilgrimage to England – dark, stormy and dramatic. I was sure to pack my red raincoat.

I was on a quest to explore Bruton, a quaint town in the southwest corner of England where author John Steinbeck spent six months studying the legends of King Arthur. It is a place steeped in history – the fabled stomping grounds of King Arthur and burial spot of the Holy Grail. Steinbeck stayed at Discove Cottage, on the property of a large estate, where he wrote in a letter to friend Elia Kazan: “I feel more at home here than I have ever felt in my life in any place.”

Coincidentally, in years prior I had also spent time in Bruton visiting a good friend who lived there. It was only during research for my master’s thesis about Steinbeck that I realized the connection. What are the odds that Steinbeck’s beloved little corner of the world would be just the same as mine?

On a blustery November morning, I began my adventure to Discove Cottage, which is normally inaccessible to the public (my local connection proved key). I wore my impermeable red raincoat and anxiously stood in the threshold of the main estate, knocking heartily on the imposing wooden door. We entered the massive home and waited in one of several sitting rooms lined with walls of bookshelves, photos of horses and delicate-looking antiques.

Through the raindrop-clad window, I spied the cottage – a modest residence on a windswept meadow. Our hosts emerged and graciously shared what little they knew about their famous former tenant. While we chatted, I flipped through a small, beige book titled “Surprise for Steinbeck.”

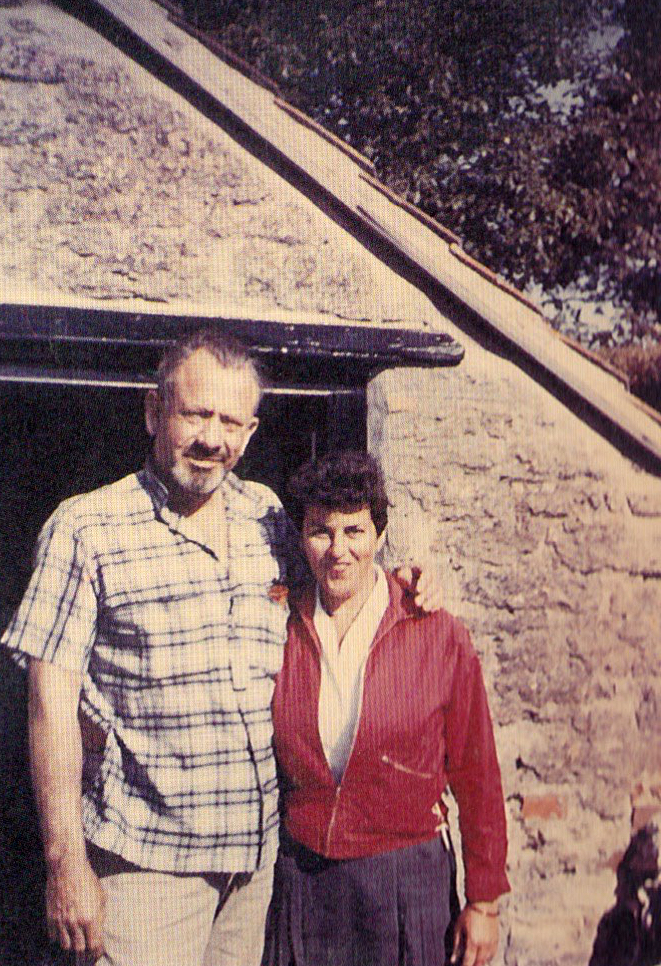

When I asked our host about it, he explained that back in 1959 an American artist named Betty Guy had been commissioned by Steinbeck’s editor to come to Bruton and paint a portrait of the cottage as a gift for him. She wrote a book about her experience, which included a color photo taped onto one of the last pages with the caption: “John Steinbeck and Betty Guy, 1959, taken by Elaine Steinbeck.” Betty was a young brunette woman about my age wearing a red jacket with zipper pockets. She was small next to the towering Steinbeck but exuded confidence.

We finally made our way to the cottage and from the outside, it was just as I expected – quintessentially British. Vines crawled up the white stones and an overgrown path led us to the front door through a wild, unkempt garden.

Wandering through the creaky rooms, we made our way upstairs and admired the view from Steinbeck’s writing nook. In the kitchen I found what I was looking for. The “flagstones. . . smoothed and hollowed by feet” that Steinbeck had written about in another letter to Kazan. “Sixty to seventy generations have been born and lived, suffered, had fun and died in these walls,” he wrote. As someone with an abiding appreciation for historic homes and the people who lived in them, reading those words during my thesis research resonated deeply.

Just outside that kitchen was the doorway where Betty and John took their photo. I replicated the scene best I could, standing in the same place as Betty had, confident in the knowledge that I had succeeded in my quest.

Upon returning home from my journey, I researched Betty Guy and was elated to find that she lived not far from me. She was the resident artist for the San Francisco Opera, and at the time, I worked for the Napa Valley Opera House – another serendipitous connection. I tracked down Betty’s address and reached out, sending her a copy of my own replication of her photo with Steinbeck. A few days later, I received an enthusiastic letter inviting me to her home for a visit.

She lived in a small, white house in the San Francisco hills, and as soon as she answered the door, the connection was immediate. Years had altered her appearance since the photo with Steinbeck half a century prior. But the bright smile remained and I felt instantly welcome.

“Where’s the red jacket?” she asked, her sassy familiarity giving me the feeling of reuniting with an old friend.

Betty’s house was an eclectic mix of personal artwork, photographs, antiques and collected treasures from her many travels. While she made us a pot of tea (she brought out the “good china” for me), I looked through a pile of watercolor paintings of European scenes piled up on the living room floor.

She related tales of dinner parties with poets, authors and artists; stories of traveling by ship across the Atlantic from the time she was twenty years old, meeting friends like Steinbeck’s editor Pat Covici who would be a part of her life forever. She laughed while sharing the memories of times spent with legends like Arthur Miller and Saul Bellow, and even a narrowly missed meeting with Marilyn Monroe. She showed me watercolors she had painted of scenes throughout Europe. One elaborate theater scene featured an interesting signature, “Oh,” she exclaimed, nonchalantly, “that was from Pavarotti.”

I begged her to tell me the story of meeting Steinbeck. It was Pat Covici who provided the key. He and his wife met Betty met on a ship while traveling through the Mediterranean in 1954 when the Covicis were traveling to visit poet W.H. Auden in Naples. The trio spent much of the trip together, cementing a life-long friendship.

Years later, during the Spring of 1959, Betty stayed as a guest of the Covicis while preparing to leave for her annual painting trip to Europe. Pat had received a letter from Steinbeck describing the cottage in England where he was staying, expressing his intense fondness for the place. And so, Pat commissioned Betty to go to England and paint this cottage as a surprise Christmas gift for the Steinbecks.

After chatting for hours, Betty presented me with my own copy of “Surprise for Steinbeck,” and I was immediately transported back to that blustery day in England. She signed it “As Ever – Betty Guy.” We looked at our photos side by side and laughed at the similarities – both of us in red raincoats, bright-eyed, knowing we were standing on hallowed ground.

She shared the story of meeting Steinbeck at Discove Cottage after being caught while she attempted to covertly capture the house on canvas. Steinbeck welcomed the charming American artist into his home, and Betty spent several meals with him and his wife, Elaine, chatting over wine, cementing a friendship that would last a lifetime.

In the early 1990s, Betty and Elaine met again while traveling in Australia. It was the first time since their time together in Bruton – 30 years prior – that the two were face-to-face. Betty presented her book to Elaine and expressed her gratitude for their kindness those decades prior. A few years later, Betty visited Elaine in New York City and found that her “little Steinbeck book” was displayed prominently with Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize for Literature.

Betty and I remained friends for the last few years of her life. I cherished our time together and continue to think of her often. It was a meeting fifty years in the making – the result of a chance meeting on a ship in the Atlantic Ocean, creating a web of serendipity that ultimately connected three Americans in England – a writer, an artist and a student. We had different inspirations but ended up a part of the same story, proving that legacies are often preserved in unexpected ways.

Julie Dalrymple has always had an obsession with old homes. Once she started studying English in college, she focused on the homes of literary figures and began seeking them out for adventure. You can follow her adventures at her blog iterary Legacies (literarylegacies.wordpress.com) or her website juliedal.com.