Elizabeth Gilbert’s biography of Eustace Conway began as an article for GQ in 1998, but her affection for Conway began some time before that. She fondly recalls her first meeting of Eustace in 1993, coming to the conclusion not long thereafter that he was, in fact, The Last American Man, which aptly became the title of her 2002 book.

Reading Gilbert’s work, it is clear that she is a talented and captivating writer. Weaving Conway’s life and personal anecdotes with historical tales and literary legend, she paints a broad picture of a fading frontier landscape, in which Conway is the remaining figure. Yet, as I read this biography, a nagging question planted itself in my brain. Sure, Conway is fascinating. He has clearly succeeded in some remarkable feats in his unique life. He has canoed 1,000 miles on the Mississippi River, hiked the entirety of the Appalachian Trail, rode across the country on horseback, and then once more with a horse and buggy. His life’s work has culminated in the creation of Turtle Island, an education and retreat center where he lives and works, promoting the naturalist lifestyle. But is he ‘the last American man?’ Surely, that is a tall order.

Compared on the Turtle Island website to Thoreau, Conway had “gone to the woods to live deliberately, fronting only the essential facts of life, to see if he could not learn what it had to teach, and not when he came to die discover that he had not lived.” It is a romantic notion, and in parts of her biography, Gilbert does indeed romanticize Conway. After reading the book, one has to ask, is this romanticism justified? What does it mean to call Conway ‘the last American man?’ How does this nomenclature bode for men who live in apartment complexes and buy their steaks in a grocery store? And, if Conway is ‘the last American man,’ what does that mean for women?

Gilbert is the first to admit that Conway is not your prototypical mangy loner who lives in the wild sustaining himself on  squirrel meat and scraps he finds in other people’s dumpsters. He is a publicist’s dream and “the press loved him because he was perfect. Eloquent, intelligent, courteous, intriguing, and blessedly photogenic” (68). She acknowledges the fact that this ideal of ‘the last American man’ is one that is at least partially superficial. Had Eustace not been so charismatic, this story could have been quite different.

squirrel meat and scraps he finds in other people’s dumpsters. He is a publicist’s dream and “the press loved him because he was perfect. Eloquent, intelligent, courteous, intriguing, and blessedly photogenic” (68). She acknowledges the fact that this ideal of ‘the last American man’ is one that is at least partially superficial. Had Eustace not been so charismatic, this story could have been quite different.

Gilbert admits early in her work that “Eustace was hard to resist,” and this becomes especially clear with each tale of ill-fated romance (24). A common thread throughout the book, and Conway’s life, is the proverbial trail of broken hearts he left along the actual Appalachian Trail. Each love story more devastating than the next, these are not run of the mill conquests. An Apache doctor, an Appalachian folk singer, an Aboriginal rock climber. Eustace Conway lived in the middle of nowhere, with little connection to the outside world and yet he could not have met more compatible women if he had a Match.com profile written in the stars. Some of these women offer Gilbert their reflections of Conway, and for the most part there seems to be a consensus. Women that were once strong and independent turned into submissive cheerleaders when paired with Conway, giving up much of their own identities to support his vision of Turtle Island. They were often ignored, held to impossible standards and harshly judged, yet many of the women reflect on the love they still have for Conway and the romantic notion that things may have or should have worked out differently. His first love, Donna, has since married another man but still “believes that she was put on this earth to be Eustace Conway’s” (79).

Gilbert is most well-known for her popular 2006 memoir, Eat, Pray, Love, the story of a woman finding herself in the midst of depression and divorce. She has since written a follow-up in the form of her 2010 work, Committed, which deals with her skepticism surrounding the institution of marriage. According to the author’s website the book explores “questions of compatibility, infatuation, fidelity, family tradition, social expectations, divorce risks and humbling responsibilities.” It is interesting that Gilbert, a modern woman cynical about marriage, seems to have such an affinity for Conway, whose unyielding ideals of the opposite sex are extremely obstinate and old-fashioned. He tells one woman he hopes she will bear him thirteen children and when both the woman and Gilbert balk at the statement, he states, “one hundred years ago a woman wouldn’t have been scared by that idea” (178). In this instance, Gilbert is the first to gratefully point out that it is no longer one hundred years ago, but at other times throughout the text she reflects poetically on this same past as a time when real American men rode horses and carried knives, just in case.

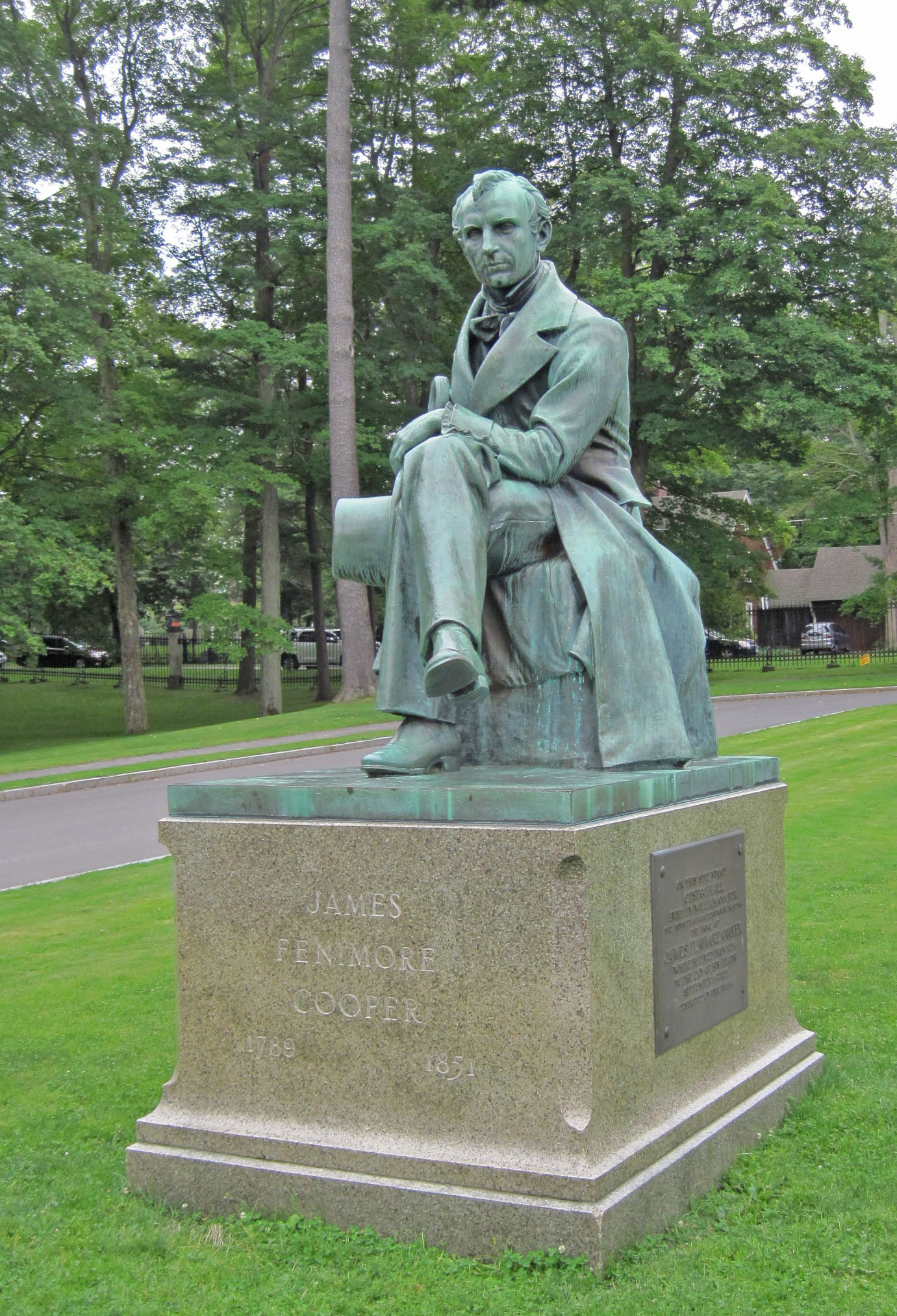

Gilbert walks a fine line between idealizing Conway and exposing his humanity and intrinsic failings, which show chiefly in his interactions with women. When musing on the idea of the ‘American man,’ Gilbert uses the example of James Fenimore Cooper’s Deerslayer, a conception of a man who will fight for a woman’s honor but remains unmarried, a lone wolf, living a frontier life of strength, self-control and solitude. She paints a rendition of Conway that is flawed and emotionally damaged, but redeemable. After all, ‘the American man’ traditionally rides alone.

Conway has always maintained a delicate balance in his life, between his need for control and his desire to be loved; between his private life of wilderness survival and his place in the public eye teaching others to do the same. Ten years after the publication of The Last American Man, Conway made his reality TV debut this past May on the History Channel’s aptly titled Mountain Men. What would Conway’s younger self think of this endeavor? A man who denies himself the indulgence of matches becoming a part of the modern day reality television epidemic has a tinge of irony to it. But ultimately Conway is not one to become a cliché. He will do whatever it takes to spread his message, “to save our nation’s collective soul” (13). He is a tenacious and meticulous dreamer, who may know how to handle a horse better than most, but he is not the first American man (or woman) to submit to such a romantic worldview and he won’t be the last.

*

Gilbert, Elizabeth. The Last American Man. New York: Penguin, 2002.

2 comments

I just finished reading the book and yes, my immediate thought was I hope we’ll have a follow-up or at least an article by Gilbert to answer some of the questions the book left us with (ie Did he ever find Mrs. Right?). Like many, I was deeply intrigued by this story –even if parts were romanticized (but who can blame her)– but it left me feeling melancholy by the end — perhaps partly due to Eustace’s reflections upon his own psychological fatigue and limitations, but also my own role in a society that values material accumulation. But I’m very grateful for the path he’s tread.