By Hannah White

Boston is a city rich in literary history that many famous writers including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry James, and Henry David Thoreau once called home. But as I embarked on my short journey to my state’s capital city, I had one woman in mind: Louisa May Alcott. Though she is often associated with the Concord, Massachusetts “Orchard House” that inspired her most famous novel Little Women, Louisa and her family lived in various places in Boston both when Louisa was a young adult and later, at the end of her life.

Alcott has had a resurgence in popularity recently after the 2019 film adaptation of Little Women starring Saoirse Ronan, Florence Pugh, and Emma Watson–to name just some of the all-star cast–was released and received critical acclaim. After watching this film last year, I developed a newfound interest in the author’s life, because though it is considered a work of fiction, Little Women is categorized as heavily autobiographical with Josephine “Jo” March, the novel’s heroine, representing Alcott herself.

The 2019 film focuses on the March sisters’ coming-of-age years. Jo, a tomboy like Alcott, is left feeling as though the strong bond between her and her sisters is torn apart after oldest Meg marries and Beth dies of scarlet fever. Jo is strongly against marriage in a world where women struggle to be anything without a husband, and when her closest friend and neighbor Laurie professes his love for her and proposes, she refuses his offer. Alcott herself said:

“I am more than half-persuaded that I am a man’s soul put by some freak of nature into a woman’s body … because I have fallen in love with so many pretty girls and never once the least bit with any man.”

Alcott has mused that every boy she knew claimed that they were who inspired the character of Laurie, but she writes in her letters that he was not an American boy at all but a Polish one whom she met abroad in 1865.

And while Alcott was not even interested in writing such an ordinary tale about her and her sisters lives, her editor insisted that she write a tale that would appeal to “little girls,” and appeal to them it did. Young girls who read early pages of the book called it “splendid!” which inspired Alcott to continue with the project, which she finished in an impressive amount of time. How much time?

In one of her letters, Alcott writes, “Began the second part of “Little Women.” I can do a chapter a day, and in a month I mean to be done. A little success is so inspiring that I now find my “Marches” sober, nice people, and as I can launch into the future, my fancy has more play.” Characteristically, she continues: “Girls write to ask who the little women marry, as if that was the only end and aim of a woman’s life. I won’t marry Jo to Laurie to please anyone.”

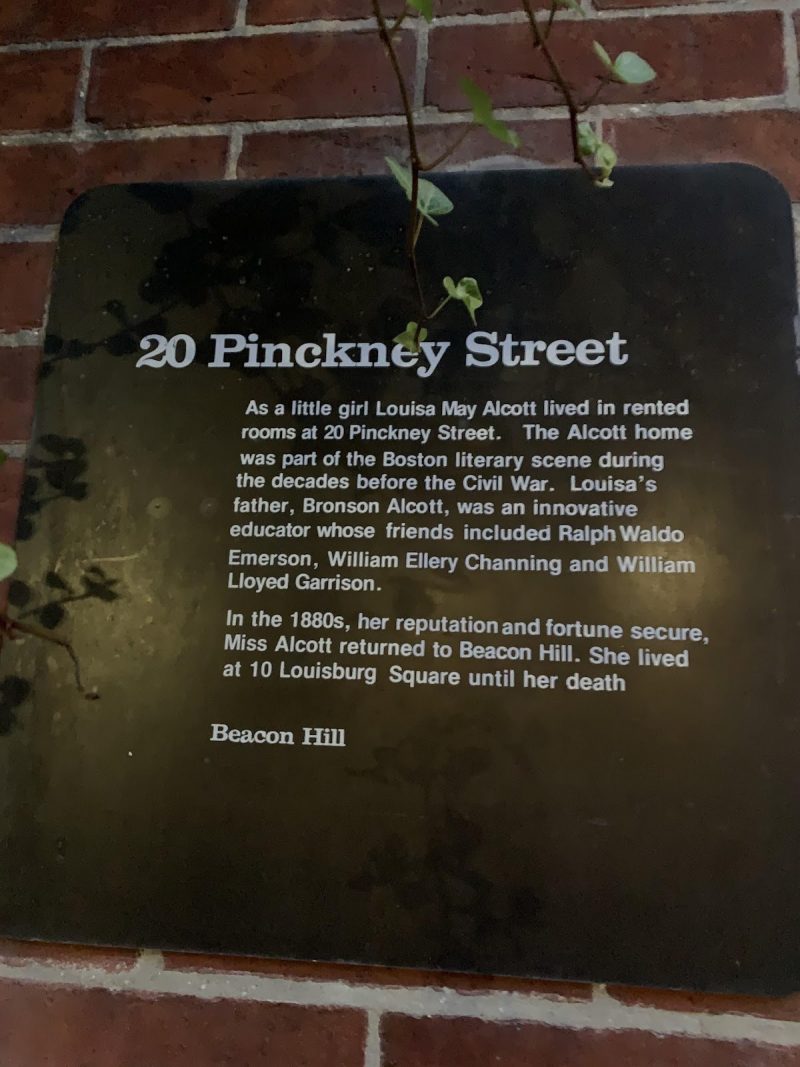

As I began my walk up the cobblestone streets of Beacon Hill just as the sun was beginning to set, the lampposts began to light up the unusually quiet streets, so secluded from the nearby hustle and bustle of the rest of the city. I made my way to 20 Pinckney Street and felt the surrealness of this moment as I came across the address, which is now a private residence, marked by a plaque that explained the literary significance of this place.

Alcott lived in a rented room on the third floor of this residence, where she resided when her first book of short stories Flower Fables was published in 1854 when she was 22, the same age I am as I stand at the base of the steps she once walked on. The residence itself is like most of the homes on this street, a quaint brick beauty featuring window boxes lush with greenery.

Alcott was the daughter of Transcendentalist Bronson Alcott, who was a famous, but impractical, educator who struggled to provide for his family. Early in her life, Alcott became concerned about the welfare of her family as they often lived in extreme poverty, much like the Marches of Little Women did. Alcott took up any job she could as a woman to help support her family including teaching, domestic work, and eventually sending her written works to editors for publishing. Little Women itself begins with a sigh from Meg, the eldest sister: “It’s so dreadful to be poor!”

Though she eventually left Boston to return home to Concord (join LT on our trip to Concord this Fall!), she returned toward the end of her life, purchasing a beautiful five-bedroom Greek Revival style home on 10 Louisburg Square–which I also visited–just a short walk from her previous Boston residence. She moved there after the death of her mother and sister May, and lived there with her ailing father and May’s infant daughter Lulu, who was named for Louisa, and remained until her death in 1888 at the age of 56, just two days after her father passed.

Alcott wrote her first and last published works while living in these homes. She leaves behind her works that have immortalized the beautiful story of her times with her family and are a testament to the importance of sisterhood in her life. Visiting these places brought me closer to an author whose work I admire greatly, and whose legacy will forever be etched in my mind and the minds of so many others.